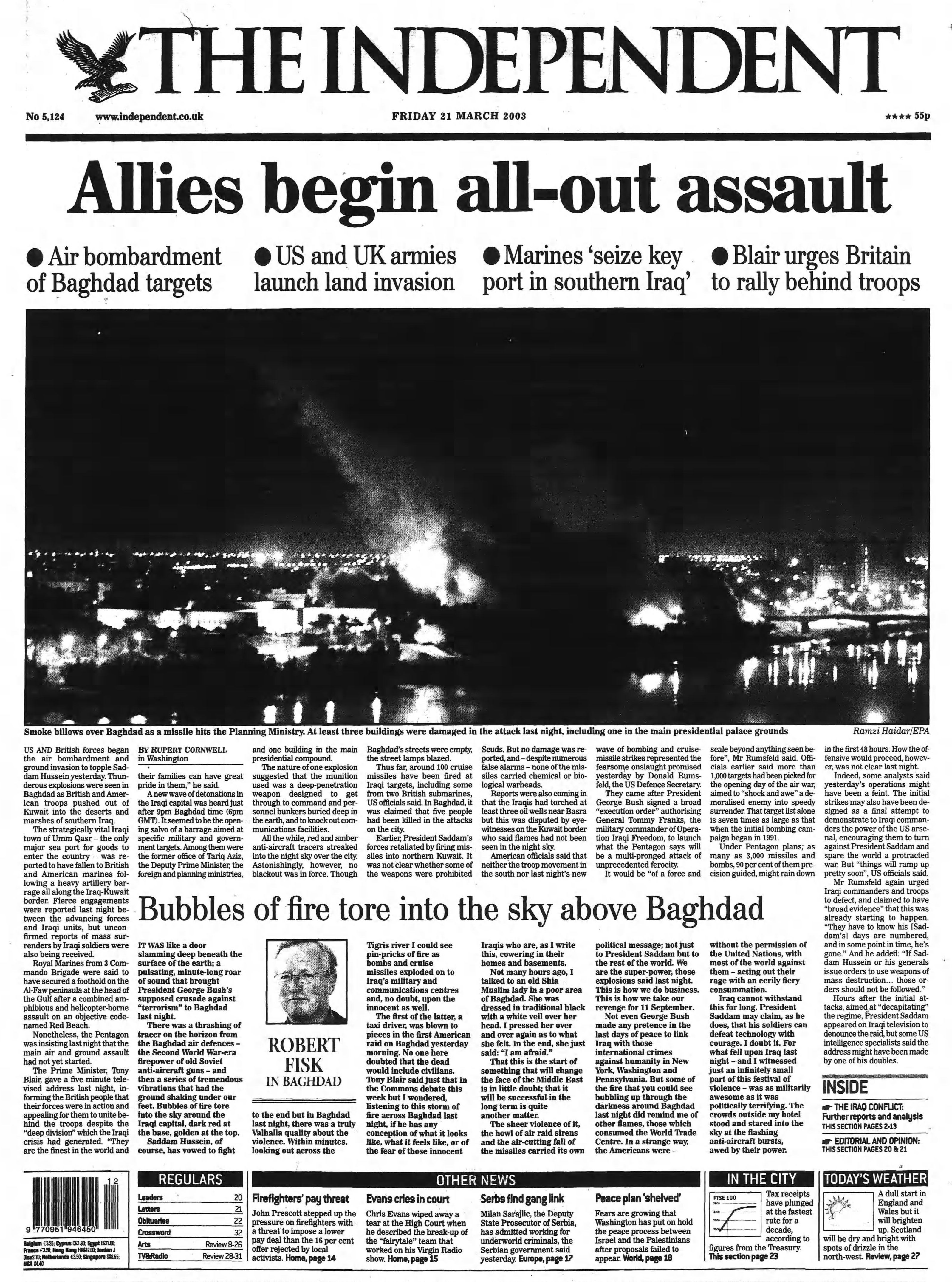

Shock and awe: Robert Fisk’s dispatch as bombs rained down on Baghdad

The Iraq war began 20 years ago with a night of bombing on capital Baghdad – and Robert Fisk was there to witness it all. Here, we reproduce that day’s reports from The Independent’s celebrated Middle East correspondent

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For more than 30 years, Robert Fisk reported on conflict across the Middle East for The Independent, and few moments were as consequential as the beginning of Operation Iraqi Freedom – that first night of “shock and awe” that marked the beginning of a disastrous war.

On 20 March 2003, as American bombs rained on Baghdad and Fisk – who died in 2020 aged 74 – was there to witness it all. With unparalleled insight, his reports capture the fear and bemusement of Iraqis in the face of terror, and the unknowable brutality of the conflict that lay ahead of them. Here are his dispatches, as published in The Independent on 21 March 2003:

Bubbles of fire tore into the sky

It was like a door slamming deep beneath the surface of the earth; a pulsating, minute-long roar of sound that brought President George Bush’s supposed crusade against “terrorism” to Baghdad last night.

There was a thrashing of tracers on the horizon from the Baghdad air defences – the Second World War-era firepower of old Soviet anti-aircraft guns – and then a series of tremendous vibrations that had the ground shaking under our feet. Bubbles of fire tore into the sky around the Iraqi capital, dark red at the base, golden at the top.

Saddam Hussein, of course, has vowed to fight to the end but in Baghdad last night, there was a truly Valhalla quality about the violence. Within minutes, looking out across the Tigris river I could see pin-pricks of fire as bombs and cruise missiles exploded onto Iraq’s military and communications centres and, no doubt, upon the innocent as well.

The first of the latter, a taxi driver, was blown to pieces in the first American raid on Baghdad yesterday morning. No one here doubted that the dead would include civilians. Tony Blair said just that in the Commons debate this week but I wondered, listening to this storm of fire across Baghdad last night, if he has any conception of what it looks like, what it feels like, or of the fear of those innocent Iraqis who are, as I write this, cowering in their homes and basements.

Not many hours ago, I talked to an old Shia Muslim lady in a poor area of Baghdad. She was dressed in traditional black with a white veil over her head. I pressed her over and over again as to what she felt. In the end, she just said: “I am afraid.”

That this is the start of something that will change the face of the Middle East is in little doubt; that it will be successful in the long term is quite another matter.

The sheer violence of it, the howl of air-raid sirens and the air-cutting fall of the missiles carried its own political message; not just to President Saddam but to the rest of the world. We are the super-power, those explosions said last night. This is how we do business. This is how we take our revenge for 11 September.

Not even George Bush made any pretence in the last days of peace to link Iraq with those international crimes against humanity in New York, Washington and Pennsylvania. But some of the fire that you could see bubbling up through the darkness around Baghdad last night did remind me of other flames, those which consumed the World Trade Centre. In a strange way, the Americans were – without the permission of the United Nations, with most of the world against them – acting out their rage with an eerily fiery consummation.

Iraq cannot withstand this for long. President Saddam may claim, as he does, that his soldiers can defeat technology with courage. I doubt it. For what fell upon Iraq last night – and I witnessed just an infinitely small part of this festival of violence – was as militarily awesome as it was politically terrifying. The crowds outside my hotel stood and stared into the sky at the flashing anti-aircraft bursts, awed by their power.

Rumbling explosions mixed with calls to prayer

Initially, the city of Baghdad was stunned by the onset of war. For more than an hour, I watched the tracers racing across the pre-dawn sky above the city and the yellow flash of anti-aircraft batteries positioned on a ministry roof. The sound was impressive – the Iraqis have always been good at London Blitz-style sound effects – but by first light the few rumbling explosions were already mixed with the call to the Fajr prayer from the minarets of Baghdad.

How many times under siege over the past 1,000 years, I wondered, must that call have echoed across this city?

If this was the start of George Bush’s “war on Saddam”, it was unimpressive. Two dull thumps of sound far to the south yesterday morning and a burst of tracer and anti-aircraft fire overhead, and all you could conclude was that the Anglo-American conflict had begun with a whimper, not a bang. Thirty-five Cruise missiles – at a cost of $40m (£25m) as well as four attacks by aircraft – could not destroy Saddam Hussein. In other words, the Americans missed.

And, within an hour, at 5.30 yesterday morning, there was President Saddam himself on Iraqi state television, specifying the exact minute and hour of his post-attack appearance, looking tired perhaps but very much the gravel-voiced Tikriti we have come to know. “You will be victorious, Iraqi people,” he announced. “Your enemy will go to hell and will be killed, God willing.” As always, he did not forget his repetitive military rhetoric. “Use your sword, don’t be afraid. Use your sword. Don’t fear anybody. Use your sword and it will be your witness.”

So Round One to President Saddam. All day, the Iraqis pondered what on earth the Americans were doing. They had heard how Mr Bush was talking up a “coalition” of 35 nations, although they know well that only the British are prepared to fight alongside the Americans. They could not comprehend why Mr Bush, having boasted of the “shock” and “awe” of his air bombardment, should have begun like this. They expected a lion’s roar. And all the Iraqis got was a mouse, a “target of opportunity”, as the Pentagon called it, that simply missed.

Meanwhile, life of a sort went on in the capital.

A few Iraqis bought their all-too-government-controlled papers, printed too late for the air raid, but filled with the usual exhortations to fight. Only a few food shops were open; my search for vegetables and fresh fruit was hopeless. There were more soldiers on the streets and policemen in new steel helmets with plastic camouflage strips and squads of young men digging pits and surrounding them with sandbags. Yet I saw only two armoured vehicles in the entire city and most of the troops grinned at journalists and dutifully gave “V” for victory signs. Could they have done anything else?

There was much discussion in Iraq – as there must have been in Europe and America – about President Bush’s extraordinary suggestion that his war “could last longer and be more difficult than expected”. An Iraqi businessman, lunching at one of the few remaining city hotels to stay open, concluded that the difficulties of the Bush conflict had been deliberately kept from the Americans and British until it was too late to turn around. Even the scarce Westerners in Baghdad were floored. As one of them put it: “He hadn’t told us that before.”

Around Baghdad, President Saddam’s soldiers are digging in. On a 20-mile journey out of the city yesterday, I saw troops building artillery revetments on the approaches to the city and military trucks hidden under motorway overpasses – and barracks already deliberately abandoned by their soldiers. These are standard tactics for any defending army – the Serbs did just the same before the Nato bombardment in 1999 – while every major facility was guarded by Baathist volunteers and local tribesmen.

At one grain silo I visited – there were still two Australian female human shields there – almost every other worker was armed with a Kalashnikov rifle. The Iraqi minister of trade, flanked by two dozen Iraqi cameramen, turned up to express his gratitude to the two ladies. They beamed into the cameras although later, of course, when the war is over, they may find their participation in this bit of theatre something to forget rather than to remember. It all depends, of course, on what bats fly out of the box if the United States “prevails” – as Mr Bush likes to say – and how the world then looks back upon President Saddam’s regime.

But yesterday, it was still very much alive. Every railway crossing was guarded by soldiers and militiamen, most crossroads boasted a military checkpoint. Yet Iraq is a country that has already been at war for too long. The unpainted houses of the suburbs, the untended bougainvillaea, the empty wagons and idle diesel locomotives that haunt the railway yards, speak of tiredness and economic ruin. The platforms of the great Baghdad railway station – an empire folly built by the British in the post-1914-18 war mandate complete with pseudo-Islamic dome – are lined with grass and weeds. What a place for Messrs Bush and Blair to fight over, one couldn’t help thinking. And it was only back in Baghdad, where you can watch the butane gas burning off from the oil refineries, that it was possible to remember what has made Iraq so tempting a target since 1917.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments