Raqqa: 'Liberated' former Isis capital still gripped by fear, full of booby traps and bombed to oblivion

The Wars in Syria: Unlike in other Syrian cities bombed or shelled to the ground – and even in Mosul in Iraq – there is at least one district that has survived intact. Returning to Raqqa four months after Isis was driven out of its ‘capital’, The Independent finds that is not the case here. The city’s destruction is total

Cascades of broken concrete line the streets of Raqqa. Few people are about and those who are look crushed and dispirited. An 80-year-old woman who says her name is Islim is scrabbling in the debris looking for scraps of metal and plastic to sell. She explains that she is trying to look after the wife and daughter of one of her sons who was killed by a mine.

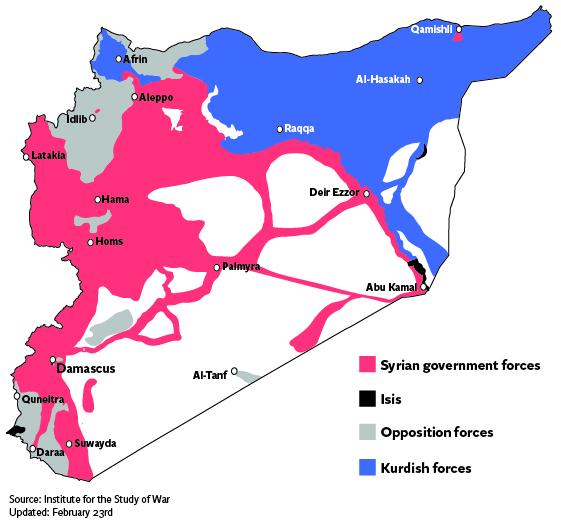

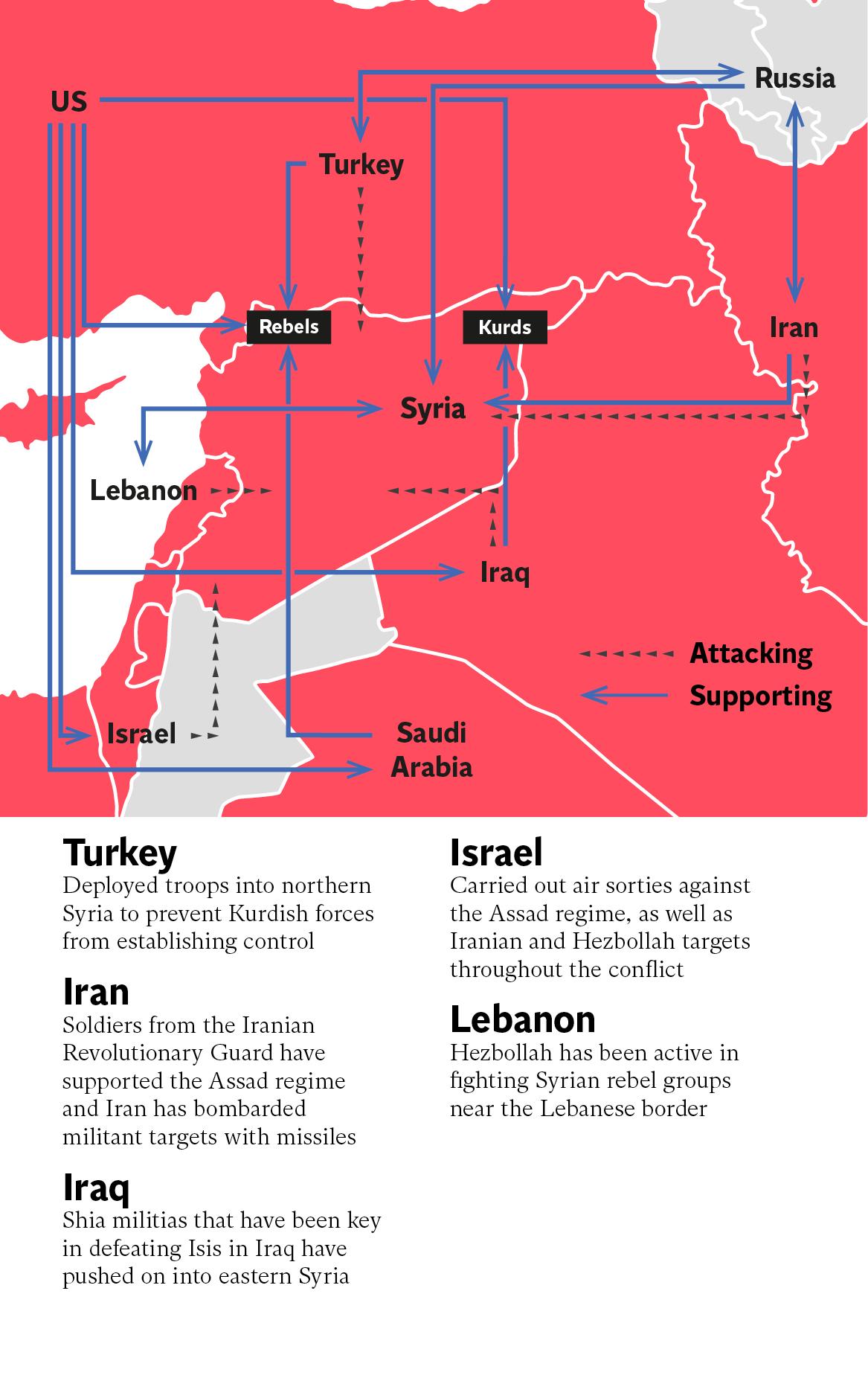

The Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), backed by US air and artillery strikes, captured Raqqa from Isis on 20 October last year after a four-month siege. The destruction is apocalyptic. Houses, hospitals, bridges, schools and factories are gone, turned into heaps of broken masonry. There is no electricity and little water.

“After the war we were at zero and we are still at zero,” says Dr Saddam al-Hawidy. He complains that foreign aid organisations come and look at the ruins of the city, but then leave and are never seen again. The final siege was only the devastating culmination of years of degradation that predates Isis rule. When the much-hated government rule collapsed there was nothing to put in its place. “My father died because the kidney dialysis unit in a local hospital was hit in a Syrian government air strike in 2015,” Dr Hawidy said.

A few districts escaped the worst of the bombing by the coalition, but none are unscathed. Inside the old walled city, we meet Ahmed Mousaqi, a middle-aged former building worker specialising in ceramics, who complains about the high price of buying a minimal amount of electricity from a private generator. He says he survived the siege, though Isis kept herding him and other civilians held as hostages from building to building.

His brother Ahmed, a motorcycle mechanic, was not so lucky. “Isis fighters took over part of his house and it was hit by an air strike,” he says. “He was killed along with five members of his family.” He adds there is little aid available for people like him because as soon as you say you are from Raqqa “they think you belong to Isis”.

Some 150,000 people have returned to Raqqa, though they are not very visible on the streets. A few shops have reopened but there not many customers and business is slow. Beside an ancient ruin called “The Ladies’ Castle”, Basil Amar as-Sawas has a shop selling doors, some of which he makes himself, while others he buys from people whose houses have been badly damaged but they have been able to salvage some of the fittings.

He says there is little money around and those who have any are reluctant to spend it while the situation remains so uncertain. Some people whose houses have survived “are selling them to businessmen because they need the money”. He has two small children below school age but for other people the absence of schools – mostly destroyed or badly damaged – is another disincentive for thinking of a return to Raqqa.

Another danger faces those whose homes were not hit in the battles: Isis was notorious for its copious use of mines and booby-traps. Its fighters specialised in placing well-concealed bombs in the homes of people known to oppose their organisation, and who had fled the city, but were likely to return when the siege was over. One member of the local council was killed when he impatiently went home before the limited demining operation had cleared his house. A reason why so little aid is distributed is the difficulty of finding distribution points for food and medicine that have been declared safe. Sarbast Hassan, an electrical technician working to restore the electricity supply, says that “we can’t even work in the city because of the mines”.

There is an extra charge of fear percolating everywhere in Raqqa that makes it different from the many other Syrian cities ravaged by war since 2011. It stems primarily from the three-and-a-half years of sadistic and pitiless Isis rule which has left everybody in the city traumatised. “Daesh is in our hearts and minds,” says Abdel Salaam, who is in charge of social affairs for the council. “Five-year-old children have seen women stoned to death and heads chopped off and put on spikes in the city centre.” Others speak of sons who killed their and fathers who did the same to their sons. Some of these atrocity stories may be exaggerated but, given the Isis cult of cruelty, many of them are likely to be all too true.

The memory of Isis terror will never go away and is accompanied by a more concrete fear that some of the movement have survived and are reorganising. Commander Masloum, one of four SDF field commanders in charge of security in Raqqa, dismisses this as an exaggerated rumour and says that there have been no recent Isis attacks in the city. He had investigated reports of “sleeper cells” but so far these had turned out to be untrue. Even so, security is tight and a curfew begins at 5 pm after which everybody must be off the streets. The roads leading to the city have checkpoints every few miles manned by locally recruited security forces.

In other Syrian cities bombed or shelled to the point of oblivion there is at least one district that has survived intact. This is the case even in Mosul in Iraq, though much of it was pounded into rubble. But in Raqqa the damage and the demoralisation are all pervasive. When something does work, such as a single traffic light, the only one to do so in the city, people express surprise.

Reminders of the grim rule of Isis are everywhere. The tops of the pointed metal railing surrounding the al-Naeem Roundabout are bent outwards because that is where severed heads were put on display. A couple of hundred yards away is what looks like a square manhole which is the entrance into an elaborate system of tunnels which Isis dug under Raqqa.

The horrendous past of the city has been succeeded by the prospect of a dangerous and uncertain future. “People here are frightened of everybody: Isis, Kurds and the Assad regime,” says a local observer. They may prefer the Kurdish-led SDF to Isis, but the choice between the Kurds and the Syrian government is more difficult to make. “They know that the Assad regime will be more merciless towards anybody who had dealings with Isis, though they may just have been selling them food or other goods,” says one frequent visitor to the city. “On the other hand, they have never liked the Kurds and at least the Assad regime is Arab like them.” Like most Syrians, the people of Raqqa are faced with a choice of evils – and nobody knows more about what evil rulers are capable of doing than they are.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments