Mullah Omar dead: Afghan Taliban struggles to maintain unity in the wake of leader's death – as exclusively seen letters apparently reveal

The terror group have named deputy leader Akhtar Mohammad Mansour as his successor, but the handover has exposed deep divisions among top commanders

Your support helps us to tell the story

As your White House correspondent, I ask the tough questions and seek the answers that matter.

Your support enables me to be in the room, pressing for transparency and accountability. Without your contributions, we wouldn't have the resources to challenge those in power.

Your donation makes it possible for us to keep doing this important work, keeping you informed every step of the way to the November election

Andrew Feinberg

White House Correspondent

The radio silence gave way to frantic conversations. Local Taliban commanders sought reassurance. Mullah Omar, the mujahedin commander of Kandahar, had finally been declared dead and along the porous border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, confusion reigned. Listening to the hurried conversations in Kandahar on Wednesday night were the Afghan border police.

“What are our orders now?” one Taliban soldier near the Pakistan city of Quetta said. “We don’t know,” another replied. “Is Mullah Omar dead? Who is leading us?”

A border police officer, 32, who has lost six members of his family to Taliban attacks, told The Independent that district commanders of the Afghan Taliban were unsure whose orders to follow. “They don’t know who their leaders are,” the police commander said. “The Taliban are worried and confused. They are not fighting they are just talking on the radio.”

Final confirmation of the long-suspected demise of Mullah Omar, the one-eyed Taliban leader who sheltered Osama bin Laden after the World Trade Centre attacks, has threatened to splinter the Taliban into rival factions: those who will enter peace talks, and those who will not.

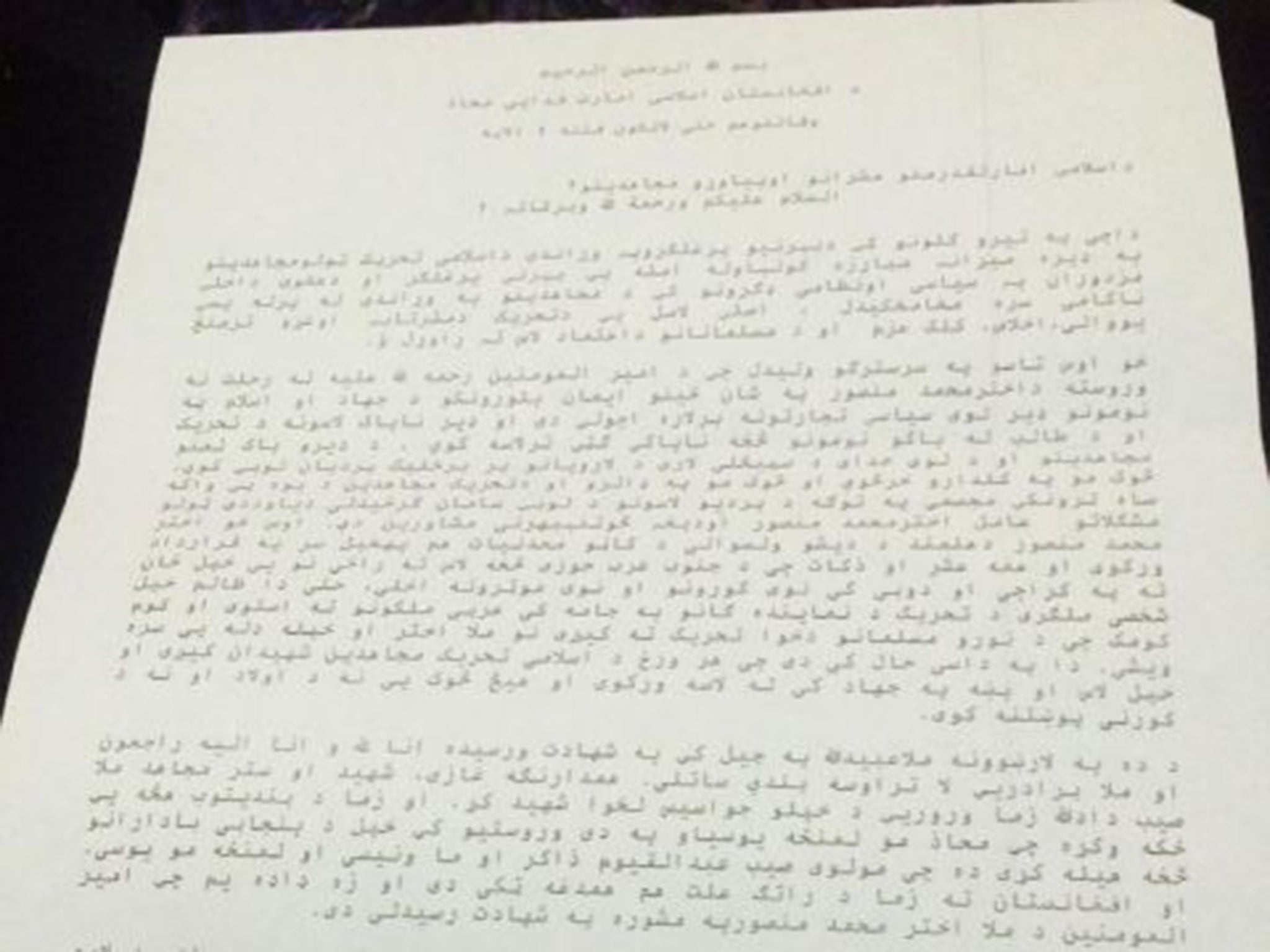

But The Independent has seen evidence that, at least nine months ago, senior commanders within the Taliban knew of their leader’s death and were already plotting who would succeed him. Letters allegedly intercepted by Afghan intelligence, and written nine months ago by two Taliban commanders – Mullah Mansour Dadullah and Mullah Abdul Qayum Zakir – appeared to urge Taliban members to rebel against Mullah Omar’s then deputy, Mullah Akhtar Mansour.

In Quetta, the Taliban’s seven most powerful figures met to discuss what should happen next – and from it, Mullah Mansour emerged as their new leader.

Soon after, it was announced that Friday’s second round of peace talks with the government of President Ashraf Ghani had been cancelled. “In view of the reports regarding the death of Mullah Omar and the resulting uncertainty, and at the request of the Afghan Taliban leadership, the second round of the Afghan peace talks, is being postponed,” said a statement from Pakistan’s foreign ministry.

The letters said to have been seized by Afghan intelligence both address members of the “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan” and accuse Mullah Mansour of plotting to kill Mullah Omar.

The first, apparently from Mullah Dadullah, says: “I am sure that the Emir of the Faithful [Omar] was martyred on the advice of... Mansour. In every province, provincial committees should carry on their own jihad struggle until we know who is the new leader. Especially those great dearest mujahedin, under my command, that they should distance themselves from Mullah Akhtar Mansour and his group.”

It adds: “I say that soon people like Mullah Akhtar Mansour and other snakes like him will suffer such pain that, as a result, the soul of the all the good martyrs of the movement will find peace.” The letter accuses Mullah Mansour of “using the good name of the Taliban group for most impure profits”.

The second, apparently written by Mullah Zakir, accuses Mullah Mansour “and other corrupt agents like him” of breaking off from the leadership “in the hope of taking the inheritance of the movement”. It adds: “The creator of all this problem is… Mansour and his Punjabi advisers. There is no doubt that, God forbid, the martyrdom of the Emir of the Faithful [Mullah Omar] was caused by Akhtar Mohamed Mansour.” There is no evidence to support either commander’s claims.

The Afghan government has said Mullah Omar died in a Karachi hospital “suspiciously”. Sources in Kabul claim that he may have contracted tuberculosis. A statement purportedly from Mullah Omar’s brother, Mullah Abdul Manan, and his son, the Taliban commander Mullah Mohammad Yaqoob, apologised for “any mistakes Mullah Omar [made] during his rule of Afghanistan”.

Sirajuddin Haqqani, who led the so-called Haqqani Network’s campaign of terror in Afghanistan, was named as Mullah Mansour’s deputy. The move was seen as an attempt to avoid infighting between Mullah Mansour and Haqqani, whose father rose as a mujahedin leader favoured by the US in the 1980s. The Haqqani Network is based in North Waziristan on the border between the two countries, and is believed to have introduced suicide bombing to Afghanistan.

The Taliban’s new leader, Mullah Mansour, is understood to favour peace talks. “They [Pakistan] want to bring in someone who can speak, negotiate and play a visible role [in the peace process], that is Mansour,” said Amrullah Saleh, the former head of Afghanistan’s National Directorate of Security.

He said: “It is all calculated. It is all an ISI [Pakistani intelligence] game. The time for the mythical figure is gone. Someone reachable and touchable has to be brought in. That is Mansour.”

On the Shomali Plain, a stretch of once-fertile land north of Kabul where Mullah Omar’s retreating Taliban poisoned wells, cut down trees and destroyed crops in 1997, there was little hope that Mullah Mansour’s leadership would lead to change.

Khalid, a farmer whose lands were destroyed by the Taliban, said: “Mullah Omar burnt down our gardens and our vineyards. He was brutal and I’m glad he has gone. But he was always a myth. Now we want peace. We don’t want to go back to how things were before.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments