Revolution on the streets of Lebanon

The lack of national solidarity, the devotion to sectarianism, the ceaseless squabbling for power, the abuse and corruption... Robert Fisk on the deep-seated and historical obstacles that have prevented the country from becoming a modern state

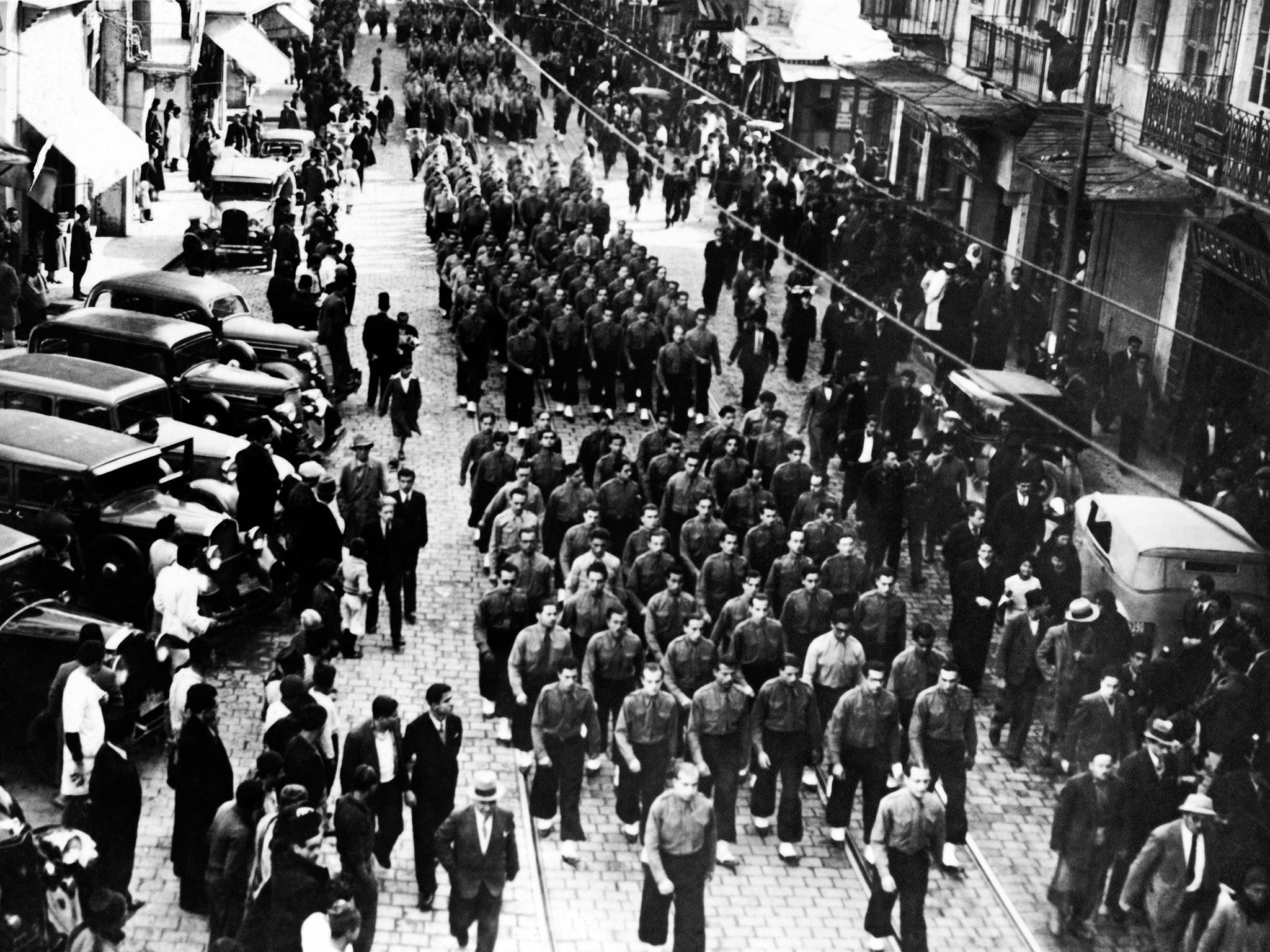

Democratic and non-sectarian protesters furious at administrative corruption, condemning the parliament as businessmen and landowners whose MPs could be bought and sold, demanding non-confessional elections and a popular vote for the president. So now the old cliché: does that sound familiar?

Well of course it does. But this was Beirut in November 1938, and the National and Democratic Congress had been brought together by the Lebanese Communist Party. It included Lebanon’s middle classes, economists, socialists, shopkeepers, students and even trade unionists of all religions, along with the wealthy elite opposed to the traditional "zaim'’, the big families who had dominated the country – as they still do – for more than a century. It went nowhere.

They protested the continued and oppressive mandate rule by the French – who had all along demanded a Christian president for their favourite Middle East statelet – but then came the Second World War, when the 1940 fall of France briefly handed Lebanon to Vichy rule, and the country’s "liberation'’ by the British and the Free French in 1941; after which, demands for independence from the French briefly united Muslims and Christians. They stood together as Lebanese nationalists.

Sectarian differences – as usual under foreign occupation – were less important than freedom. When the French locked up the recalcitrant Lebanese authorities, both Christians and Muslims, in the old keep at Rachaya, there were violent demonstrations across all of Lebanon. But by the time the French decided to leave, Lebanon’s sectarian system re-emerged. So did Syria’s. Both countries were to share the same independence day. And the same grim legacy of confessionalism, which the French had insidiously encouraged during their 1923 to 1946 mandate.

Yet while France’s mandate had largely benefited the Christians, for whom General Henri Gouraud enlarged the new Lebanon at Syria’s expense, even the French administration was sometimes irritated by the constant confessional claims of Christians and Muslims. The Blum Popular Front government in Paris was actually criticised by the Lebanese for its non-sectarian outlook. Now that the Sunni majority in Syria had been separated from them, the Sunnis of Lebanon found themselves a minority. Brigadier Stephen Longrigg, one of the more unemotional historians of this period, quickly spotted how the country’s abiding weaknesses could be observed even after the First World War: “The lack of national solidarity, the devotion to sectarian or personal ends, the ceaseless squabbling for place and power, the interventions of religious dignitaries…the difficulty of purging waste, abuse and corruption…the excessive claims of confessionalism.”

When the world depression crushed Lebanon’s economy (inevitably linked to France’s own finances), there were widespread strikes, street protests and violence. Wages fell by 50 per cent; a faint parallel to present-day Lebanon’s crisis, but in the 1920s the protests were largely instigated by butchers, taxi-drivers and lawyers. The Christians were divided – as they are today – but the Shia Muslims were largely disregarded by Christians, Sunnis and the French. Poor, largely uneducated, regarded as almost a "foreign'' element in Lebanon – as some Sunnis and Christians might claim they still are – it was their brother Alawite community in Syria which captured the attention of the French. But inside Lebanon, now cut off from the majority Sunnis in Syria, the Shia were now becoming a powerful minority — just as the Sunnis of Lebanon, separated from their brothers and sisters in Syria – were a less powerful minority.

In Lebanon, alas, the growing power of Nazi Germany began to exercise its influence over the Lebanese. The Syrian Social Nationalist Party, which advocated a "greater'’ Syria, emerged complete with brown shirts and leadership-worship; today, it counts 100,000 members in the Middle East, and its red, white and black emblem of a whirlwind – it uses the same flag today — resembles the Swastika, as it was intended to do.

The Christian Maronite Phalange emerged with parades, squads of paramilitaries and a young football champion, Pierre Gemayel, as its leader. His inspiration was his visit to the 1936 Nazi Olympics in Berlin. “And I saw then this discipline and order,” he told me in his old age. “And I said to myself: ‘Why can’t we do the same thing in Lebanon?…And we in the Middle East, we needed discipline more than anything else.” Syria, by the way, caught the same plague in the late 1930s. It had its ‘White Shirts’ and its ‘Steel Shirts’ movements.

Interestingly, the Lebanese – then and now — wished to smother their sectarian identities with Western political nomenclature. A Martian man or woman landing in Lebanon – were they not partial to Arabic coffee – might think they had arrived in Europe. The Phalange was supposed to belong to the Party of Lebanese Unity. Later they would become the Social Democratic Party. And thus today, confessional and sometimes iron men hide behind the National Liberal Party (Chamounist Christian), the Free Patriotic Movement’(Aounist Christian), the Future Movement (Saad Hariri’s Sunnis) and the Progressive Socialist Party (Jumblatt’s Druze). Amal (the Hope movement led by Nabih Berri) is the more formal Shia party. Only the Hezbollah – the Party of God – associates itself by name with its (Shia) religious faith.

A Martian man or woman landing in Lebanon – were they not partial to Arabic coffee – might think they had arrived in Europe

Perhaps the most relevant academic study for the protestors on the streets of central Beirut today remains the late Kamal Salibi’s wonderful history of Lebanese society, A House of Many Mansions. A Protestant himself, Salibi asked whether the different communities in Lebanon should “be represented in government by leaderships that stood for their true confessional or tribal ethos, or should their representation be from elements more given to reason and moderation?” In the first case, the government “could degenerate into an arena for the settlement of traditional confessional…feuds, and this could only result in political chaos”. In the second, the representation of the country in government “would not reflect its true social nature” – presumably because "reason and moderation' in Lebanon was not as easy to find as Salibi might have wished.

And here we arrive at the nuclear centre of the Lebanese crisis. Could Lebanon become a modern state by de-confessionalising its politics while remaining socially sectarian? If you accept that Muslims and Christians could not marry in Lebanon – and that divorce (a highly profitable income for the churches of all faiths) could only be decided by clergymen – could you really cast all this aside and elect your leaders on the basis of their capabilities rather than their religion? Especially when the Christians, however divided, saw themselves as representatives of European civilisation under constant threat of the Muslims, while the Muslims felt they belonged to Arab nationalism – or, later, to Islamic nationalism or simply the ‘nation’ of Islam?

Salibi believed that government and opposition in Lebanon, Christian and Muslim leaderships, wished to prevent economic development since this would “make the blind see”; the education of the towns and village people of Lebanon – these are my words — was a danger to the educated elites. Since the sophisticated, wealthy Christian and Sunni Muslims controlled the banks and the economy, they would also be blamed when corruption was exposed. Economic crises could be blamed on foreigners – first the Palestinian refugees, today the Syrians and the Iranians – but the first two decades of Lebanon’s independence were of almost unparalleled economic success.

An unwritten and largely unspoken agreement exists whereby Hezbollah will not protest at their disproportionate lack of representation so long as they are allowed to maintain a heavily armed militia

Then in 1966 Intra Bank, directed by a Palestinian Christian, collapsed. Almost as powerful as the Bank of Lebanon, it controlled major companies throughout the country, including the national airline, property development, tourism and industry. The bank, as Professor Fawwaz Traboulsi would state explicitly in his own history of Lebanon, financed elections, distributed cash gifts in the guise of loans and paid bribes of every kind. Recent research suggests that western financial institutions may have brought about the collapse – Intra had more assets than liabilities when it was destroyed – but the results were catastrophic. Smaller banks in Lebanon collapsed; and there was a massive flight of capital from the country – just as there is today.

Indeed, it is worth asking whether the present revolution in Lebanon – whose protestors demand an end to corruption and sectarianism and a new constitution – would have broken out today if the economy of the country, long ago bailed out by European powers, was still enjoying the profligacy of the 1950s and 1960s. After the 1975-90 civil war, as long as Lebanon’s currency remained on a 1,500 to one par with the US dollar, its economy worked.

Remittances could be a substitute for taxation, property secure against inflation or financial collapse. Corruption was sustainable – by the banks, by the political leadership, by business leaders — on the grounds that the sectarian system protected the country under what was called the National Pact. If this was to break down – if parliamentary representation based on confessionalism (a Christian as president, a Sunni as prime minister, a Shia as speaker of parliament, etc ad infinitum) was no longer able to protect the Lebanese economy – then both the financial and sectarian system would lose credibility. And this is what has eventually happened.

Ironically, and tragically, those who now demand a new constitution, a new way of governing Lebanon, an end to institutional corruption, have no allies. And those who were ready not so long ago to die for the freedom of the south of the country – the Hezbollah – turn out to be the most powerful supporters of those who have caused the people’s impoverishment: because seats in parliament and the cabinet are ultimately more important to Hezbollah (and Syria) than the political change which the pro-Iranian party might in other circumstances have demanded in Lebanon.

There is a good reason for this. Every politician in Lebanon will privately acknowledge that the Shia, if they are to be represented in parliament according to their real current population, should hold more than the 27 seats to which they are presently entitled. An unwritten and largely unspoken agreement exists whereby the Hezbollah will not protest at their disproportionate lack of representation so long as they are allowed to maintain a heavily armed militia.

In other words, the largest Shiite movement can keep its weapons – which are infinitely more powerful than those of the Lebanese army — providing it doesn’t ask for more seats in parliament. Fearful of upsetting this balance – always described by journalists as a ‘delicate balance’, although it is in fact both sectarian and unfair – the Lebanese prefer to accept an ‘illegal’ Shiite paramilitary force than a future Islamic Republic.

Or at least, this is how it is often explained. The list system of elections ensures that voters must also support candidates of a different sect to their own, but this in itself creates a fraudulent ‘democratic’ illusion: that political leaders are popular outside the communities to which they belong.

Supporters of Christian President Michel Aoun’s Free Patriotic Movement – run by the president’s son-in-law Gebran Bassil – are aligned with Hezbollah (and thus with Syria). But Bassil is not just a party leader and the president’s son-in-law, he is also the Lebanese foreign minister. He even turned up at Davos this month, claiming that his private jet expenses to Switzerland were paid for by “a friend”.

Bassil is the principal target of the Beirut protestors. He claims he is squeaky-clean. And so say all of us. But I know of no one in Lebanon who does not have a verifiable tale of corruption. I am well aware, for example, of a deal agreed in the last 24 months between a most prominent Lebanese politician – not Bassil — and a most prominent Lebanese banker. The politician asked the banker to make a huge loan to a relative. The banker was told he would lose his job if he did not pay. He paid. I know the names, I know the amount, I know the date.

How can a member of the Lebanese security apparatus afford to pay tens of thousands of dollars for his daughter’s wedding when Lebanon’s population has not enjoyed 24-hour-a-day electricity for 45 years?

No doubt their lawyers could sue me if I wrote more. But every Lebanese has a personal – and in most cases, provably true – story of such malfeasance. Massive corruption is not just a claim. It is a fact. How can a member of the Lebanese security apparatus, for example, afford to pay tens of thousands of dollars for his daughter’s wedding when Lebanon’s population has not enjoyed 24-hour-a-day electricity for 45 years? If the golden days of Lebanon’s laissez-faire economy could return, this might be forgiven or forgotten for another half century. But Lebanon is the third highest indebted country in the world. The Lebanese pound is about to implode. And for most of its people, the money is running out.

Riad al-Solh, Lebanon’s first post-independence prime minister, sought to integrate the country’s religious communities into a nation — and to do so in such a way that the sects lived together in friendship and love rather than through fear and passivity. Solh, one of those imprisoned by the French at Rachaya in 1943, described the country’s confessional system as a poison. But as my late colleague Patrick Seale once wrote, the unresolved contradiction between a society built on “ancient confessional solidarities” and “a nation state built on a shared national identity” continued to plague Lebanon. And does so today.

Lebanon’s modern history contains all the clues to the current revolution. I used to say that its tragedy (and yes, I still principally blame the French for this) was that the country can never become a modern state. If it were to ‘de-confessionalise’, it would cease to exist – since sectarianism is now the identity of Lebanon. The country was a Rolls-Royce with leather seats and a cocktail cabinet – but with square wheels. I’m not sure that so facile a metaphor is any longer worthy of the grim future currently facing the Lebanese.

When the ruling classes can only reproduce themselves in ever more corrupt fashion and when those they are supposed to represent demand only their departure, you have a revolution in more than one sense. Yes, what’s happening in Lebanon is a continuation of the Arab awakening of almost a decade ago. But as we all know, when a population decides that its rulers must go, that’s often the moment when larger, more powerful foreign nations move in to take control. Then the local dictators emerge, eager to do the bidding of those foreigners who care so much for the poor and huddled masses yearning to breathe free.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments