From Truman to Clinton, Bush to Biden, how US presidents tried to make peace in the Middle East

As every American president since Truman, who recognised Israel as a state after its foundation in 1948, has discovered, engaging with the region is unavoidable – but attempts at intervention carry a high risk of failure, writes Sean O’Grady

It’s ironic that Joe Biden has become so embroiled in the Middle East. After decades in public life, and a period as vice-president under Barack Obama, when he witnessed a peace initiative collapse on launch, he had a shrewd idea that there wasn’t much in it for him. So, unlike Obama and Donald Trump, he didn’t even appoint a special envoy to focus on the Israel-Palestine conflict when he took office in January 2021.

It was not just a matter of managing expectations – more of abolishing them. There were to be no peace conference, no Camp David Accords, no treaties signed on the White House lawn. Though in many respects a conventional Democrat, Biden broke with the strategy adopted unsuccessfully by Obama, and more successfully by Bill Clinton and Jimmy Carter, and walked off the field. He accepted the peace treaties between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan that Trump had helped to broker, known as the Abraham Accords (the name Abraham was a reference to Judaism, Islam and Christianity being Abrahamic religions). Biden also stuck with Trump’s controversial and provocative decision to recognise Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. And that was supposed to be that.

But, as every American president since the war has discovered, the Middle East is unavoidable. Even those presidents with no interest in being “blessed peacemakers” found that the region could sometimes burst dramatically into their lives. It happened, literally and tragically, on 9/11. After the almost non-stop peace initiatives of the Clinton years, George W Bush wanted to concentrate on the domestic agenda. Yet he soon found himself confronted with Islamist terrorism on a previously unthinkable scale, and in the heart of America itself: the World Trade Center, the Pentagon and, almost, the Capitol.

Only eight months in, his presidency was dominated by the search for Osama bin Laden and the “war on terror” in Afghanistan, which subsequently extended into Iraq. The results live with us today, but the origins lie partly in the Israel-Palestine dispute. After all, one of Bin Laden’s demands was an end to Israel. In his 2002 “letter to America”, he mockingly wrote: “It brings us both laughter and tears to see that you have not yet tired of repeating your fabricated lies that the Jews have a historical right to Palestine, as it was promised to them in the Torah. Anyone who disputes with them on this alleged fact is accused of antisemitism ... The blood pouring out of Palestine must be equally revenged. You must know that the Palestinians do not cry alone; their women are not widowed alone; their sons are not orphaned alone.”

President Harry S Truman, after some debate with his officials, recognised Israel de facto soon after its foundation in 1948, and de jure in 1949; John F Kennedy established the “special relationship” with Israel in 1961. Yet neither they nor Dwight D Eisenhower, Lyndon B Johnson, Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan or George HW Bush showed much interest in spending time on what has always seemed an intractable problem. Their main function was in trying to contain terrorism (the hijacking of aircraft being a scourge of the era) and achieving ceasefires after periodic wars and invasions: Eisenhower was the first to be forced to do so, in 1956.

In the Suez crisis, America had to financially blackmail the British to withdraw from their joint invasion of Egypt with France and Israel. In 1974, Richard Nixon, in the dying days of his scandal-ridden presidency, tried to build on his administration’s success in helping to end the 1973 Yom Kippur war, after he’d saved Israel. As secretary of state, Henry Kissinger’s pioneering “shuttle diplomacy” ended that war; but Nixon and Kissinger couldn’t build a peace. The problems were familiar: Arab states and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) refused to recognise Israel’s right to exist, while Israelis wouldn’t engage with the PLO, which had pledged to destroy Israel using terrorism.

Then, as now, Syria was the most implacable and anti-American of the sovereign states (as opposed to militias, liberation groups and terrorists), and Nixon noted a harbinger of the future in a 1974 visit to Damascus. In an awkward meeting with the then president, Hafez Assad – the father of the present incumbent – Nixon noted: “The problems that my visit presented to President Assad were summed up in the story he told me about his eight-year-old son. The boy has watched our airport arrival ceremonies on television, and when Assad returned home that night, he went up to his father and asked: ‘Wasn’t that Nixon the same one you have been telling us for years is an evil man who is completely in control of the Zionists and our enemies? How could you welcome him and shake his hand?’ Assad smiled and said it was a question all his people will ask and why we have to move at a very measured pace...”

That also speaks to another recurring theme in Middle East diplomacy, which is the dissonance between positive private conversations and public denunciations, and why secret “back channels” via third parties – Norway in the 1990s, Qatar today – have grown to be imperative.

Intervention carries a high risk of failure, and there are few votes in it. Indeed, with powerful lobbies all around, nationally and in Congress, ready to take issue and criticise, it can damage a president’s chances of re-election. For all the accolades and peace prizes, there are few electoral rewards to be mined in the West Bank and Gaza. But it can be done, and peace brokered, under certain conditions.

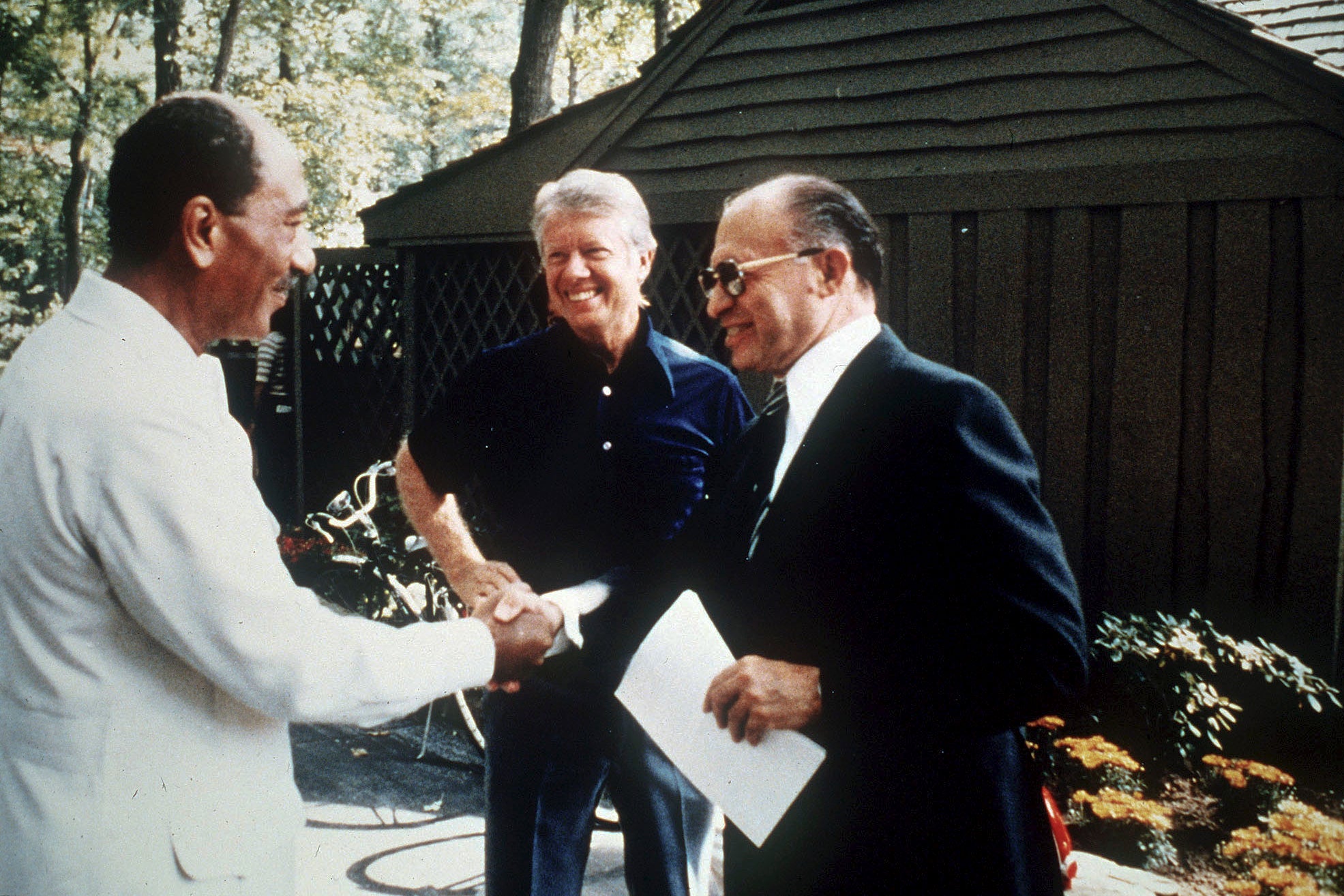

The first and most important is that at least one side has a leader who is willing to make bold decisions. For that, they need a solid national base and the credibility to deliver a deal; a belief in peace, and some sort of personal chemistry with the other participants. In the past such figures have included Egyptian president Anwar Sadat, Yasser Arafat of the PLO, King Hussein of Jordan, and two outstanding Israeli premiers, both initially sceptical and unlikely peacemakers: Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Rabin.

For example, when the newly elected Carter met Sadat for the first time, he recorded his relief in the early stages of the process that led to the 1978 peace treaty between Israel and Egypt, the first such document for 2,000 years, with echoes that reverberate down the decades: “... The PLO leaders strongly objected to two points: any recognition of Israel as a permanent nation, and the absence of specific references to the Palestinians ... Then, on April 4 1977, a shining light burst on the Middle East scene for me. I had my first meetings with President Anwar Sadat, a man who would change history and whom I would come to admire more than any other leader.”

It’s unlikely that Biden or Antony Blinken have come across such a visionary in their travels. Of course, Sadat was later assassinated for his trouble, as was Rabin not long after he’d signed the 1994 Oslo deal with Jordan, brokered by Clinton. Bravery and statesmanship are commodities that are often in short supply in the Middle East.

Trump’s peacemaking was of a slightly different kind, as he was less a broker and more an agent of Israel. Yet the successful Abraham Accords do point up another crucial lesson, which is that state-to-state treaty-making is less difficult than forging a grand multilateral framework. One obvious reason is that, while there are always presidents, prime ministers, sheikhs and kings around to hear approaches, there is often no effective voice for Palestinians – because those with such authority are not acceptable to Israel.

Where once, however fancifully, Palestinians could look to Arab solidarity, much of that leverage has disappeared. Formal recognition, normalised diplomatic relations, the exchange of ambassadors and trade were once much prized by Israel, and could thus be used as levers for a wider settlement. No longer, given the network of bilateral relations. More treaties could be concluded with Israel’s neighbours, such as Saudi Arabia, but that simply makes a resolution of the core Israel-Palestine issue more remote.

Partial peace is no peace at all, and there’s little sign of anyone in the region having the kind of vision and impatience shown by, say, Sadat half a century ago. From Biden’s point of view, the chances of going beyond a modest humanitarian deal and restarting the peace process seem hopeless.

Hamas and Hezbollah are not going to evolve as the PLO and Fatah did before them; yet the beleaguered Mahmoud Abbas, the president of the Palestinian Authority, seems in no position to deliver any promise: he’s no Arafat. So, as so often, there is no Palestinian voice. Benjamin Netanyahu, General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, and the younger Assad offer little in the way of inspiration. Nor, frankly, at this stage in his presidency, does it seem there would be much reward in Biden trying.

We are therefore unlikely to see any reprise of these words from Clinton, at the time of Oslo: “And now let the work of progress bear fruit. Here at the first of many crossing points to be open, people from every corner of the Earth will soon come to share in the wonders of your lands. There are resources to be found in the desert, minerals to be drawn from the sea, water to be separated from salt and used to fertilise the fields. Here, where slaves in ancient times were forced to take their chisels to the stone, the Earth, as the Koran says, will stir and swell and bring forth life. The desert, as Isaiah prophesied, shall rejoice and blossom.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments