Israel election: Benjamin Netanyahu's hawkish new coalition bodes ill for the peace process

An administration with ultra-orthodox and right-wing parties has been put together which has only the slightest majority - leaving the PM with an unexpectedly tenuous grip on power

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Six weeks after he was declared the clear victor of Israel’s election, Benjamin Netanyahu is expected to unveil a government with only a wafer-thin majority when he attempts to meet the deadline to form a new administration.

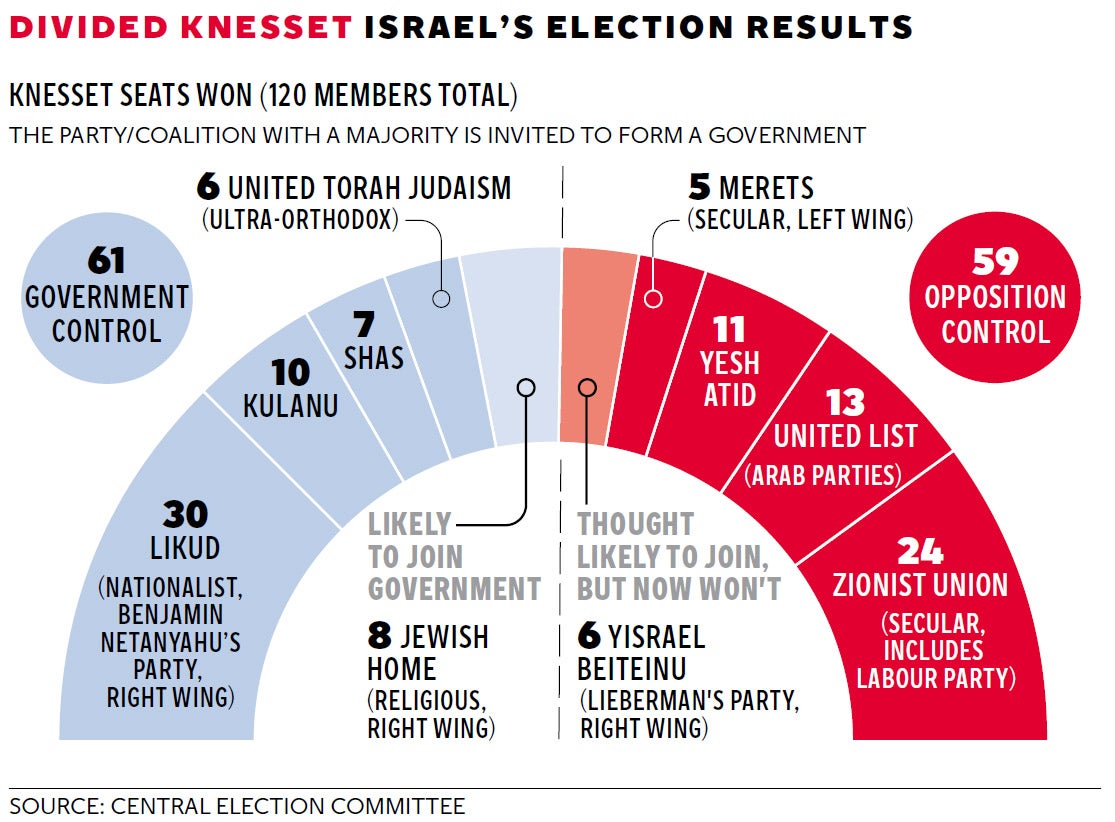

The decision by a key right-wing ally not to join the planned right-of-centre coalition means the Israeli Prime Minister will hold an unexpectedly tenuous grip on power, with an expected 61 MPs out of the 120-member Israeli parliament, the Knesset.

Mr Netanyahu’s Likud party surpassed all predictions by winning 30 seats in the March election in what was hailed as a stunning victory. He has until Wednesday evening to present his coalition to Israel’s President, Reuven Rivlin, and is still in negotiations with the right-wing nationalist Jewish Home party, which is believed to have demanded the justice ministry in return for joining the coalition.

But his hope of forming a broader government consisting of right-wing parties was scuppered on Monday when the Foreign Minister and leader of the Yisrael Beiteinu party, Avigdor Lieberman, ruled out joining Mr Netanyahu’s new administration. In the last election, in 2013, Likud and Yisrael Beiteinu stood together on a joint ticket.

Explaining his reasons, Mr Lieberman said: “Everything we saw in the agreements with the other parties and everything we didn’t see persuaded me it wouldn’t be a nationalist government but a government of opportunism and conformism.” If Mr Netanyahu fails to find the remaining seats he needs, Mr Rivlin could offer another party leader the chance to form a government, or order fresh elections.

In practice, Mr Netanyahu remains the leader with the best chance of success. He has already signed up the new Kulanu party, led by the former Likud minister Moshe Kahlon, which campaigned on a promise to tackle Israel’s burgeoning cost of living.

Shas and United Torah Judaism, the parties representing the ultra-orthodox communities, will also join the coalition, giving Mr Netanyahu a total of 53 seats.

Talks are continuing, with Jewish Home, which is led by Naftali Bennett, a one-time Netanyahu ally who was once director of the settlers’ Yesha Council. Its eight seats would push Mr Netanyahu’s alliance just across the finishing line in the Knesset.

Mr Netanyahu’s expected coalition will almost certainly represent a setback for the peace process with the Palestinians and for any real rapprochement with Israel’s biggest ally, the United States.

In the run-up to the election, Mr Netanyahu campaigned tirelessly on security issues, and especially against the deal between Western powers and Iran over Tehran’s nuclear ambitions. Describing the fragile agreement as a “bad deal”, he broke convention by addressing the US Congress, despite being invited by the Speaker of the House of Representatives, John Boehner, and not by President Obama.

On the eve of the 17 March election, he also excited ire by declaring there would be no Palestinian state while he was prime minister, backtracking from a 2009 pledge to pursue a two-state solution.

Last weekend, the former US President Jimmy Carter, who helped to broker the peace deal between Israel and Egypt in 1979, declared that Mr Netanyahu was not “in favour of a two-state solution” . Allies of Mr Netanyahu maintain he does support a negotiated settlement with the Palestinians. It is difficult to see how a government that includes the Jewish Home party could strike such a deal, however. Mr Bennett is adamant that there will be no peace deal. “You can’t occupy your own land,” he says. He favours annexing the parts of the West Bank containing Jewish settlements.

Members of Mr Netanyahu’s party have suggested that the proposed new government could soon collapse, forcing Israelis back to the polls, or leaving Mr Netanyahu searching for new coalition partners.

Speaking to the daily Haaretz, one unnamed senior member of the Likud party said: “A coalition of 61 MPs is an impossible coalition. It is enough that [senior members of the Jewish Home party] decide to flex their muscles and the government will collapse.”

Reuven Hazan, who chairs the political science department at the Hebrew University, disagreed. “There are many parliamentary systems in the world where a coalition does not have a majority,” he said. “It means that everyone is whipped because if they do not vote cohesively, they could bring down the government. What is just as important is the ideology. What you have [with this coalition] is two hawkish parties, two ultra-religious parties and a centre-right party,” he argued.

The coalition talks have gone down to the wire because of Mr Lieberman’s decision. Some have argued that he is waiting for the government to fall, rather than being part of it. Speaking on Monday, he said “it is clear that [fresh] elections will occur in 2016, maybe even in 2015”.

He also pointed to delays in passing a bill that would enshrine into law Israel’s status as a Jewish state. The country’s Arab minority is against the bill, as are some of the ultra-orthodox communities. The polls before March’s election had predicted that a coalition between two progressive parties would emerge with the greatest number of seats. Instead it fell six short of Likud’s total.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments