Iraq gets ready for life after America

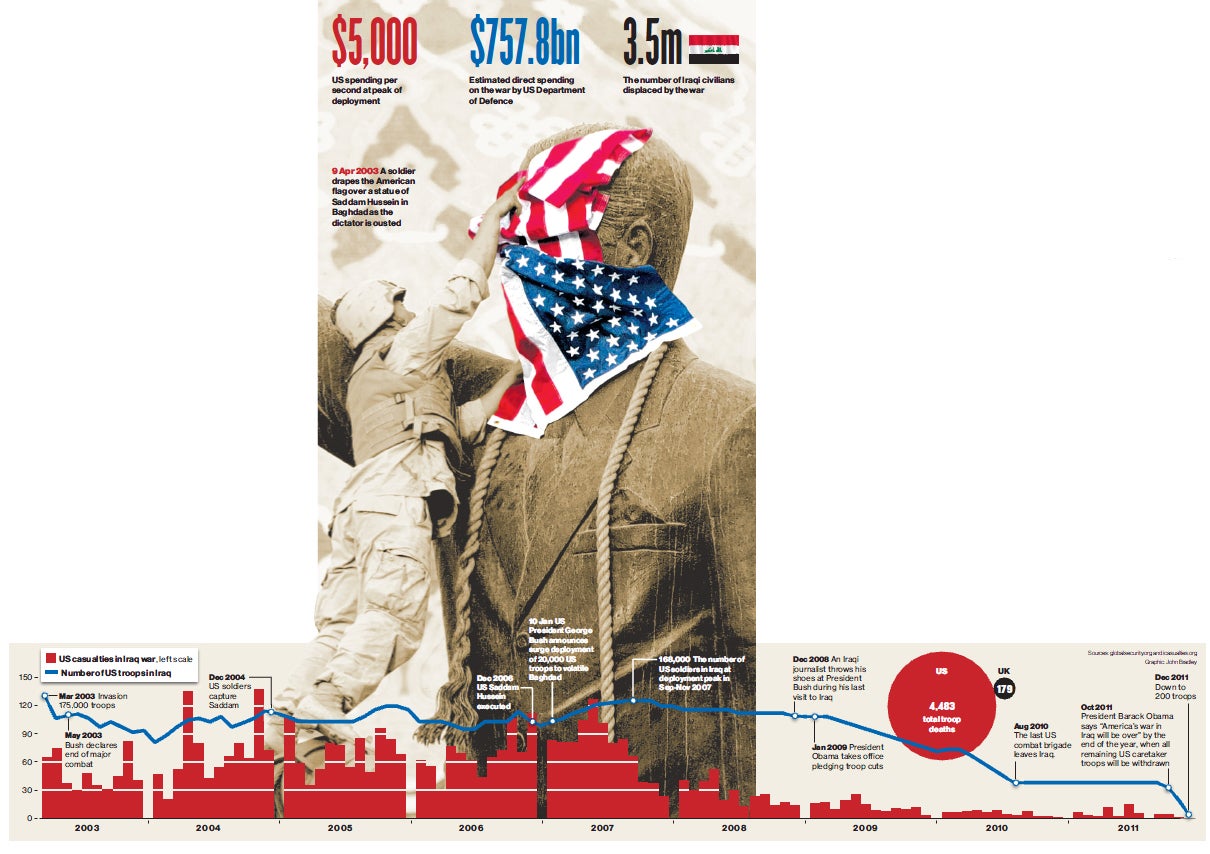

Next year will be the first since 2003 with no US troops in Baghdad. But are Iraqis ready to go it alone?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As the last US troops begin to leave Iraq so that all are out by the end of the year, what sort of Iraq do they leave behind them? Does the American departure mean that Iraq might revert to turmoil or even civil war?

US officials are seeking to avoid any suggestion this is a military retreat. They even prefer to avoid the use of the word "withdrawal" and term the final pull-out of a US army that once numbered 170,000 men in 550 bases as a "reposturing" of forces.

Iraq remains an extraordinarily dangerous country. Since the US invasion eight-and-a-half years ago, scarcely a day has passed when an Iraqi has not been killed or wounded. Casualties may be much less than at their peak of 3,000 dead a month in 2006, but they are by no means negligible.

High points of violence over the past fortnight include an attempt to assassinate the Prime Minister, Nouri al-Maliki, five suicide bomb attacks on a single day that killed 21 and injured 100 Shia pilgrims, and an attack on a prison north of Baghdad that left 18 dead. Aside from these incidents, there has been the daily drum-beat of shootings and bombings. In November alone some 255 Iraqi civilians, soldiers, police and insurgents were killed, according to Iraqi government figures.

Asked how they react to the US departure, Iraqis express a sense of unease, but are warily philosophical about what happens next. Many blame the US for the all-consuming violence that followed the overthrow of Saddam Hussein and has not yet finished. "I was young when the Americans first came here," says Mohammed Zaid, a 19-year-old technology student. "When I remember the years since, all I can think about is blood." Dr Mahmoud Othman, an independent Kurdish MP, adds: "Not many people here want the Americans to stay, apart from the Kurds, and Kurdistan was never occupied by US troops."

Ethnic and communal loyalties frequently determine attitudes to the withdrawal. Sunnis in Baghdad, victims of massacre and expulsion, feel one last safeguard against persecution by the Shia-dominated security forces is being removed. "It is not a good time for the Americans to leave," says Zaid Ahmed, 35, a Sunni doctor. "The Iraqis are not prepared to fight al-Qa'ida or Iran."

The Shia majority in the capital is more confident. Adel Hassan, 48, a middle-ranking government official, says: "Iraqis will face the same problems whether the Americans stay or go." Asked about the prospects for a civil war, he replies cynically that, if there is one, "it will be no problem for the government because the ministers all have two passports and can leave the country."

Iraqi apprehensiveness is born of fears stemming from past butchery – some 225,000 Iraqis have been killed since 2003 by one estimate – as from any prospect of a return to mass killings. "My best friend just told me she has put off buying a house until she can see what happens after the Americans go," says one woman journalist. "But maybe nothing will happen." She adds that one consequence of the Sunni-Shia battles of 2006-07 means there are now few mixed areas left in Baghdad and therefore less chance of confrontation.

The Americans have in practice played a limited role in Iraqi security since 2009. "In the last two years the Americans have had only a small influence here," says Dr Othman. This is probably an underestimate. A government minister says "the Americans help keep the leaders of the different communities within some form of consensus which is the most important challenge here".

Iraqis do not spend all their time thinking and talking about politics. For many, the biggest challenge is trying to get through the day. "Everything is always more difficult to do in Iraq than in other countries," complained one professional woman wearily. Improvements are there, but they are infuriatingly slow to come and not everybody benefits. One woman friend told me cheerily that she was getting five to seven hours' electricity, but on the same day a few miles away another friend sitting in his house wrapped in a blanket said to me gloomily that he had received just one hour's power supply.

Getting round Baghdad is easier than last year. There is more traffic and it moves faster because there are fewer checkpoints and many grey concrete blast walls blocking off streets have been removed. There are even traffic lights that operate when electricity is available. The airport road – once the most dangerous stretch of Tarmac in the world – now feels relatively safe. The burnt-out carcasses of cars that once dotted the verge are long gone and the palm trees in the central reservation have been pruned. Shops stay open late and there are no queues at petrol stations.

But, for all the government's claim to have restored peace, it does not take long to be affected by the insecurity in Baghdad. I had just arrived at the al-Rashid Hotel in the Green Zone last week when a bomb exploded, killing two people a couple of hundred yards away in the car park of the parliament building. I saw the burnt-out remains of the chassis of the vehicle and scattered pieces of debris, but I could not find a crater, suggesting that the bomb was not large by Iraqi standards.

Soon afterwards a military spokesman explained that the bombing had been part of a complicated plot to assassinate Mr Maliki and the device had been assembled in the Green Zone. What is significant here is that, for all the tight security protecting the Green Zone, al-Qa'ida in Mesopotamia – which has little connection with Osama bin Laden's group – and other insurgents still have the personnel, equipment and intelligence to launch an attack inside such a heavily defended area.

The failure to eliminate insurgents has little to do with the presence or absence of the US Army. Iraq's own forces number 280,000 soldiers and 645,000 police and frontier guards. "The problem is that we have too many intelligence bodies and some of them are in communication with the terrorists," explained one senior official. The director of one of Iraq's numerous intelligence agencies lamented that "the authorities have no real plan: they react to events day-by-day".

The problem goes deeper than this. It lies essentially in the fact that the divisions and inefficiencies of the Iraqi intelligence apparatus are symptomatic of the failings of Iraq's dysfunctional state. Political leaders advocating the different interests of the Shias, Sunnis and the Kurds have difficulty in reaching an agreement on almost anything.

Decision-making is crippled by the way in which senior politicians within a supposedly power-sharing government can veto the action of the others. Mr Maliki's sustained effort to get round this by trying to monopolise power at the centre exacerbates party differences. He takes all security decisions himself and the Shia dominate the upper ranks of the Defence and Interior Ministries.

Not all the news in Iraq is bad. The country is wholly dependent on its oil revenues, but these are expanding rapidly. "I only saw the Iraqi cabinet panic once," said a former minister, "and that was a few years ago when they feared the price of oil would drop below $50 a barrel." These revenues enable the state to pay for an enormous number of employees – the security forces alone total 900,000 men. Teachers, who were scarcely paid during sanctions, get a proper wage.

But physical reconstruction remains painfully slow. There are few cranes on the skyline of Baghdad. Corruption is at the level of Afghanistan or Somalia. Few are punished for the most blatant thefts, though one minister was recently forced to resign after signing a billion-dollar contract with a bankrupt German company and a shell company in Canada that had an address but no assets or operations.

Only in the very autonomous Kurdistan region in the north is there fast development and a government that functions effectively. As the US Army departs this month, non-Kurdish Iraq remains a theoretically wealthy but ruined country whose physical and political wounds will take decades to heal.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments