Iran goes to the polls with voter apathy high: ‘I don’t want anything to do with a system of oppression’

As the country goes to the ballot box to replace the late hardline president Ebrahim Raisi, Kim Sengupta hears from young people angered by situation at home, but also worried about what Iran may face from the US if Trump returns to the White House

In a momentous year of elections around the world, there are unexpected polls taking place in Iran with little publicity abroad, but of great significance to the country, the region and beyond.

The unscheduled Iranian election follows the death of the president, Ebrahim Raisi, last month in a helicopter crash. It comes at a time when there is fear of a wider conflagration spreading across the Middle East out of the Gaza War.

After months of escalating artillery, rocket and missile exchanges across the Lebanese border, the prospect of a direct conflict between Israel and Hezbollah, which has close links to Tehran, is higher than ever, with other Iranian allies possibly joining the fight.

Fellow members of what Iran calls the "Axis of Resistance" against Israel and the US – Shia militias in Syria and Iraq, the Houthis in Yemen – have threatened action. Tehran has declared that “any imprudent decision by the occupying Israeli regime will have one ultimate loser, the Zionist entity.”

The chances of reducing tension between the largest Shia country in the world, one which may acquire nuclear weapons in the future, and the international community will depend, to an extent, on the winner of the election: but more on two men who are not taking part in it.

No significant decision is made by the Islamic Republic without the authorisation of the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The chances of establishing good relations with the West will also be affected by whether Donald Trump gets back to the White House in November – the prospect of which looks stronger today after Joe Biden’s alarmingly stumbling performance in the US presidential debate.

Trump pulled the US out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) deal with world powers on Iran’s nuclear programme early into his presidency, after intense lobbying by Israel, the Gulf States and Saudi Arabia. He reimposed punitive sanctions on Tehran, followed up by the assassination, through a drone strike, of Commander Qassem Soleimani, the head of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC).

The collapse of the JCPOA ended the hopes of Iran reopening to the world among progressive and young voters who went on to boycott the 2021 election which brought the hardliner Raisi to power. Nuclear talks with the West led to nowhere under his government, while strong relations were established with Russia, especially since the start of Moscow's 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Javad Zarif, the foreign minister under the reformist government of president Hassan Rouhani, who signed the JCPOA, is taking part in this election as the foreign policy advisor to Masoud Pezeshkian, the only reformist candidate who has been allowed to run after vetting by the country’s Guardian Council.

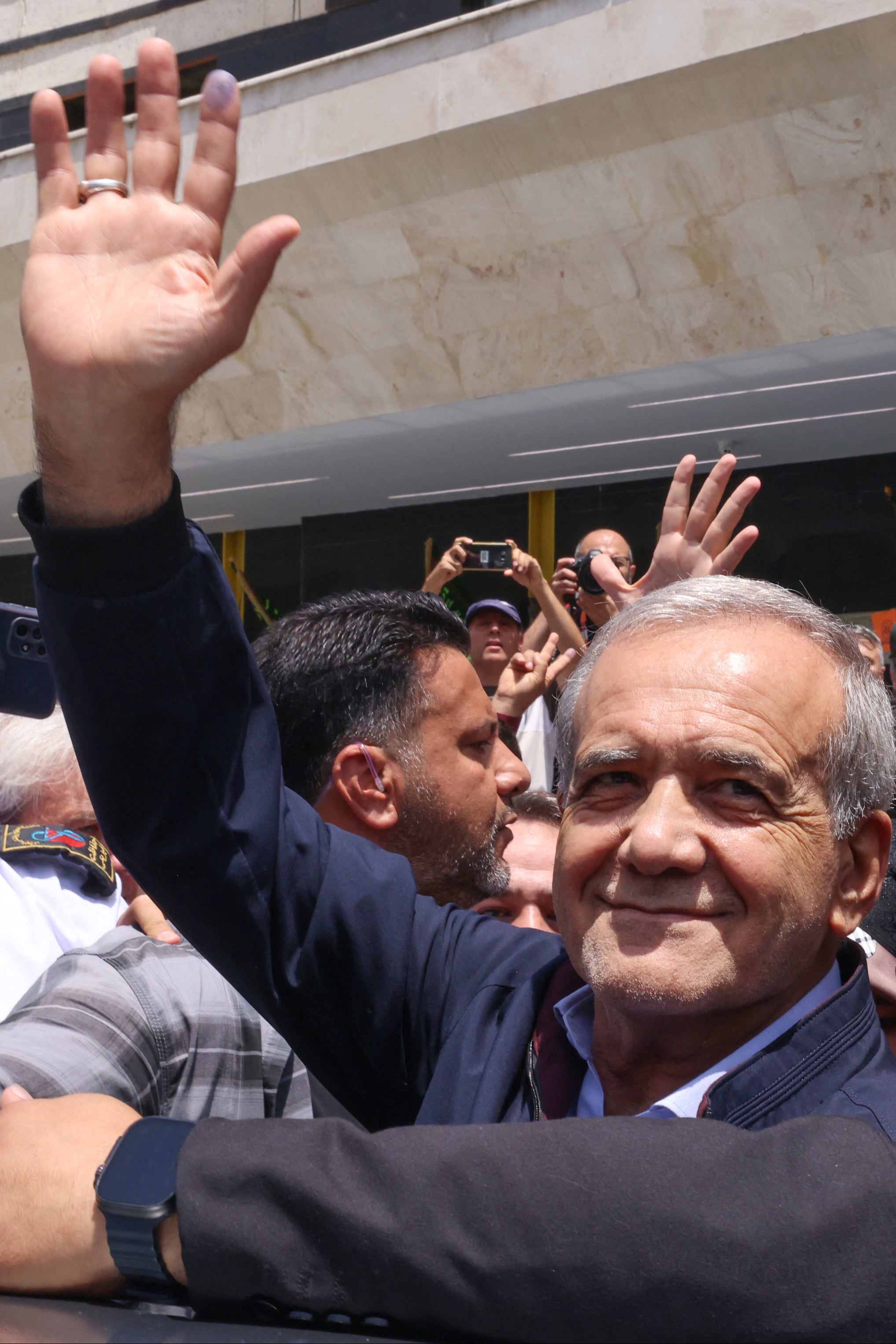

Pezeshkian, a former health minister who was disqualified from running in the 2021 election, is doing surprisingly well in opinion polls after a campaign in which he has blamed the conservative government for Iran’s economic woes by failing on the nuclear talks, and the lifting of sanctions.

Pezeshkian has spoken of improving relations with the US and the West, and not becoming overdependent militarily on Russia or economically on China. Zarif, and former President Rouhani have been vocal in criticising government policies which has led to the country’s isolation.

The two most prominent conservatives are Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, the Majlis [parliament] speaker, and a former IRGC air commander and police chief, Saeed Jalili, Ayatollah Khamenei’s representative to the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) and former nuclear talks negotiator.

Two other candidates have dropped out during the campaign and there was an expectation that either Ghalibaf or Jalili would make way to consolidate the conservative vote. A three-cornered fight may well mean that the contest will go to a second round run-off, with results in a week’s time with some of the votes going to Pezeshkian.

The reformist candidate, however, faces the problem of liberal voters staying away from the polls once again. Many young people in particular feel alienated from the governing system following the brutal crackdown of the "hijab protests" which followed the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini two years ago.

There has been renewed arrests of women over head-covering transgressions for the last two months, as well as investigation of businesses where they work, and shops which serve them – all under a new security operation called Noor (meaning “light”).

Pezeshkian has warned that the “Noor plan will take is into darkness.” But for many among the young, making up 60 per cent of the 85 million population, his words will have little effect in improving the situation. Daria, a 20-year-old living in north Tehran, said: “There are people who have real power who’ll never change their views, despite what some politicians may say. That is the reason there is no point in voting.”

The student, who did not want her family name made public, continued: “Our country and Afghanistan are the only countries which are punishing women over head-covering. Even the Saudis have become much less strict. This election isn’t going to change that.”

Her friend Afareem, 24, will also stay away. She was expelled from university after being arrested for taking part in the protests. “I don’t want to have anything to do with a system which oppresses people. It has no legitimacy,” she said.

Rustam, 33, an IT software designer, voted at a central Tehran polling station for Pezeshkian after being initially undecided about taking part. “I think he should get past the first round, and then he may have a chance in the second, who knows?” he said. “We need to improve relations with other countries, including America. We need to get the sanctions lifted”. What would happen if Trump wins in the US? “Then I think all the hope of good relations will go, just like the last time,” Rustam was convinced.

There are impassioned views on the other side that hold that Iran must not compromise with the West, and should instead get ready for aggression from abroad.

In south Tehran, economically poorer and more socially conservative than the north of the city, Ali Abbas Ghasemi, a former member of the government’s Basij miliitia who was injured fighting in Syria against Isis, asked: “What was the point of Rouhani signing that [nuclear] agreement? The Americans broke their words, as they always do. In the meantime we had weakened our defences.

“We should not trust them yet again? We should strengthen our defences. The Americans and Europeans are allowing the Zionists to slaughter families in Gaza. We need to vote to strengthen the Nezam [system] against what Israel could try to do”.

The Biden administration has refused to back Israel’s repeated threats to carry out air strikes on Iran’s military and nuclear facilities – an operation Benjamin Netanyahu’s government cannot successfully carry out without American help.

Some in the Iranian hierarchy think this may change in the future with a Trump presidency. A number of senior officials have talked of reviewing the country’s doctrine of not producing nuclear weapons. Kamal Kharrazi, an advisor to Ayatollah Khamenei, said: “We have no decision to build a nuclear bomb, but should Iran’s existence be threatened, there’ll be no choice but to change our military doctrine. In the case of an attack on our nuclear facilities by the Zionist regime, our deterrence will change.”

Antony Blinken noted this week of “statements by Iranian officials suggesting potential changes to Iran’s nuclear doctrine”. Israel’s defence minister, Yoav Gallant, met the US secretary of state, the defence secretary, Lloyd Austin, and William Burns, the CIA director, in Washington this week about Iran’s recent nuclear activity.

Whether the Middle East is pushed closer to war may depend not just on the outcome of the election in Iran, but one 6,300 miles away in the US in five months time.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments