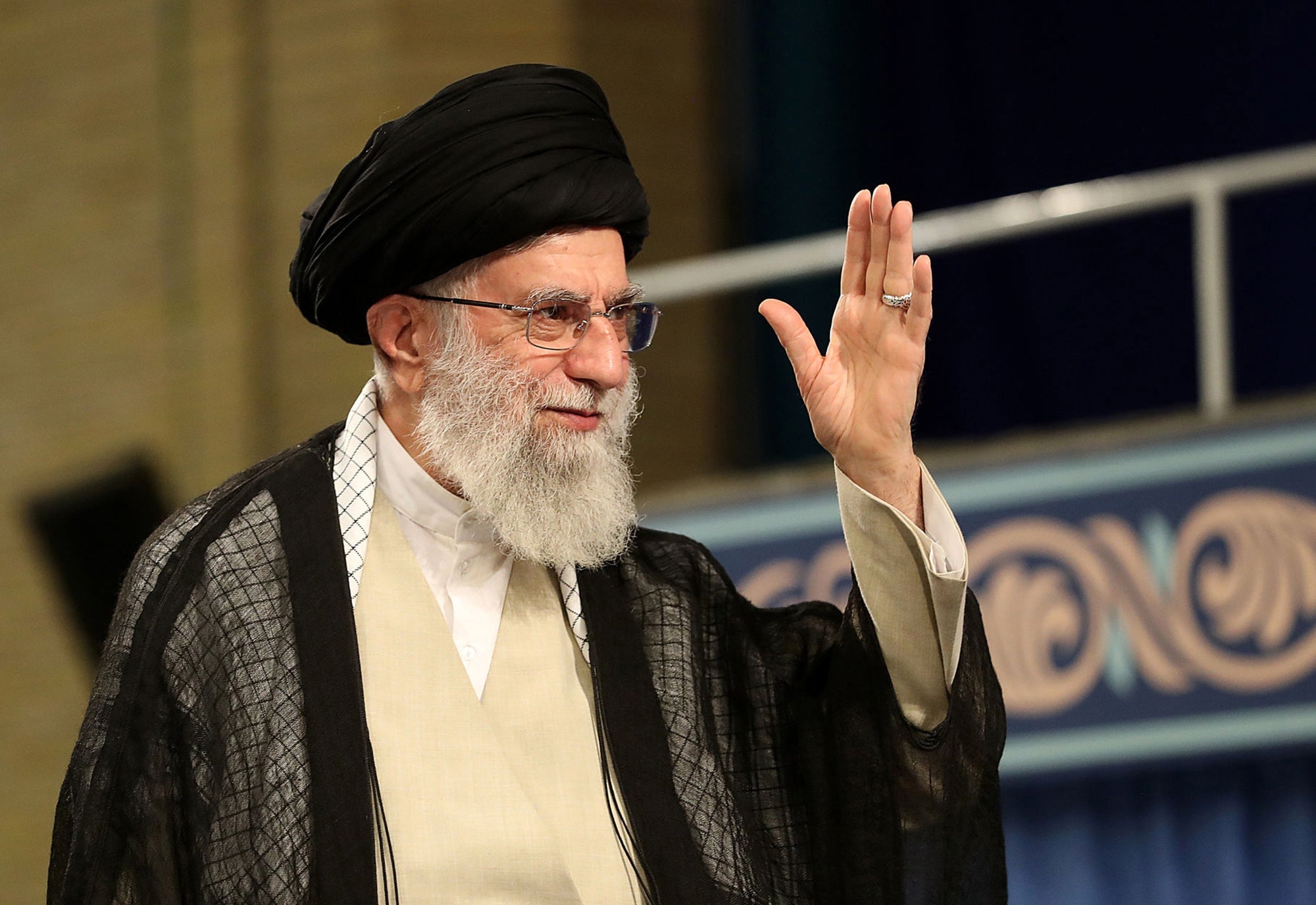

How Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei turned his position into one ‘Persian monarchs would have envied’

As the grand ayatollah turns 80, Borzou Daragahi looks back at his life and leadership of the Islamic republic

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The boy was drawn to poetry and literature, and found himself as a young man attracted to the cerebral life of big cities. But his pious, clerical father would have none of it.

Physically abusive and overbearing, the patriarch insisted that his second-oldest son attend the seminary and seek the path of the Lord, away from the political and intellectual fervour that was gripping the country.

While his older brother had defied their father, pursuing a career as a big-city lawyer, the meek, bespectacled teenager succumbed to his demands. He himself has told the story of growing up in the Iranian city of Mashhad and being mocked by other children for wearing the gowns of the seminary student.

But Ali Khamenei, supreme leader of Iran, would eventually find his own ways to overcome his father’s restrictions.

Last week, according to official records, Khamenei turned 80 years old, even though he says his actual birthday was in April.

Last month, Khamenei also marked 30 years as Iran’s top leader, a job he took on almost reluctantly after serving for eight years as Iran’s president. His tenure has crossed over with six US presidents, six UK prime ministers and four Saudi kings. Within the Middle East, only the Sultan of Oman, Qaboos bin Said al Said, has been in power longer.

And in this time, Khamenei has shaped his country, as well as the region around it, like no other. In many ways, it’s Khamenei’s Middle East today.

“He now has within his own office and within himself the sort of political authority that the Persian monarchs would have envied,” says Ali Ansari, a scholar of Iranian history at the University of St Andrews.

“He has the religious authority that no modern Persian monarch would even aspire to. He has the final say on everything.”

Scholars regard Khamenei as the architect of modern Iran. Since he took over as supreme leader, the country’s influence in the region has mostly grown, as a result of taking advantage of others’ missteps as well as his own initiatives, and a talent for turning his weaknesses against his enemies.

“I call him ‘the man of institutions’, because Iran’s institutions today, as we know them, are his inventions,” says Mehdi Khalaji, a Washington-based scholar who is writing a book about the supreme leader.

It was Khamenei who invested Iran’s Revolutionary Guard, or IRGC, with the power it has; weakened the presidency; established and shaped various councils that oversee the country’s elected bodies. It was he who decided to pursue a nuclear energy programme begun under the shah, and to give the IRGC the go-ahead to create an international network.

He now has within his own office and within himself the sort of political authority that the Persian monarchs would have envied

He has created hundreds of cultural, social, economic, political, military institutions and reinvented the Shia clergy, turning an ancient network that sprawls throughout the Middle East and south Asia into a powerful force under Tehran’s tutelage.

“One of his great achievements is to refashion the entire religious establishment by modernising and bureaucratising it,” says Khalaji. “He has changed the nature of the clergy in Iran, and the nature of the [Shia] religious network in the Middle East.”

Throughout it all, he was driven by the resentment towards powerful figures who doubted and underestimated his abilities and his credentials. The US, which Khamenei often describes as “the global arrogance”, is just the largest in a long line of forces who wrote him off.

“His obsession with the order of the world, his obsession with the idea that Iran has never been fully recognised, comes from a deeper existential obsession about himself,” says Khalaji, who has spoken extensively with people close to the supreme leader.

Khamenei came of age in 1950s and 1960s Iran, a time of tremendous tumult following the Second World War and the US-backed coup that toppled the nationalist government of Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh.

The overthrow strengthened the power of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi but also spawned an entire generation of leftists and Islamists opposed to his rule. Khamenei, the son of a cleric, was drawn to both circles, but didn’t find full acceptance from either.

“He approached literary circles, he liked poetry and the arts, and never identified himself as a typical cleric,” says Khalaji.

“The problem was that if you have the clerical robes, the intellectuals would not recognise you as one of them. If you go to the clerical circles and then talk the way he would, they do not recognise you.”

The anti-Americanism among Iranian intellectual circles of the era affected him deeply, and he continues to cling to it today.

He eventually fell in with supporters of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of Iran’s 1979 revolution, but was never one of his most prominent and powerful aides or leading critical lights. From the start, he was much more interested in politics than religion.

The world is practically carved up by the big domineering powers, and these powers consider themselves as masters of the world

“He didn’t make a lot of noise,” says Ansari. “He was and is a fairly junior cleric.”

It was Ali Akbar Rafsanjani, a white-turbaned cleric from a wealthy family of pistachio farmers and a favourite of Khomeini, who brought him into the inner circle of power, vouching for him as he shifted from Tehran’s Friday prayer leader to deputy defence minister in the first months of the Islamic republic.

After a trip to the front lines of the Iran-Iraq war, Khamenei was giving a speech at a mosque. A bomb was hidden inside a tape recorder. He survived the 1981 assassination attempt in Tehran, but it cost him the use of his right hand.

A few months later he became Iran’s president, then a largely ceremonial post. During a speech to the UN General Assembly, he extolled the glories of the revolution, and voiced solidarity with the struggles of people in Palestine, and Apartheid-era South Africa.

“Today the world is practically carved up by the big domineering powers, and these powers consider themselves as masters of the world,” he said. “The world has been divided into two parts: the dominant and the dominated.”

Unlike President Hassan Rouhani and foreign minister Javad Zarif, who both studied in the west, Khamenei had no affection for the west and continued to relish his trips to the front lines of the Iran-Iraq War, where he would build up contacts with the IRGC. “He was very interested in getting involved in military strategy and tactics,” Khalaji says.

That interest would later serve him well.

A few months after Khamenei was named supreme leader, following Khomeini’s 1989 death, he complained privately that he was bored and had little to do, according to the late Rafsanjani’s memoirs.

That was by design. Rafsanjani, then president, and others had engineered Khamenei’s rise, believing him to be too weak ever to pose a challenge, and thus would remain a figurehead. But he would outmanoeuvre them, primarily by partnering with the IRGC.

At the time, at the end of the Iran-Iraq War, many hoped the parallel branch of the armed forces would be merged into the regular military. But Khamenei had different ideas. He not only insisted the IRGC remain intact, but encouraged its entrance into politics and commerce, and oversaw the expansion of the volunteer Basij military force into an auxiliary force that served as the guards’ tentacles in neighbourhoods and villages.

It expanded its intelligence and surveillance networks, and broadened its overseas clandestine expeditionary Quds force across the Middle East.

“Khamenei didn’t have a lot of innovations in religion or political ideas,” says Saeid Golkar, a professor at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, who has studied Khamenei’s life. “Where he had ideas was in the realm of security and military power.”

His other push was in the nuclear programme, which Iran began to invest in heavily, since he came to power, as a form of deterrence against regime change. Among his final trips abroad before becoming supreme leader was to North Korea in 1989.

“If big countries threaten progressive countries, then progressive countries should threaten them in turn,” he said during the trip.

“He firmly believed a nuclear Iran would be immune from any sort of attempt of subversion and would guarantee the survival of the regime,” says Ansari.

Still, for the first decade or so as supreme leader, Khamenei was a quiet figure, mostly in the background as Rafsanjani took the lead. The visible rise in his power and presence began in 1997, when the reformist Mohammad Khatami became president in a landslide election.

Acceding to public demands, Khatami began calling for political freedoms and an open press. Something of a “Tehran Spring” was initiated as the country’s cultural and political life blossomed.

Hardliners cracked down, crushing student protests in 1999. But Khamenei’s emergence as a despot came the following year, after the newly elected reformist parliament sought to enact a liberal press law.

“He wrote a letter to the speaker of parliament saying this could not happen,” says Ansari. “We can see that as the critical moment when the reform project began to unwind. He made it clear that parliament didn’t make the laws.”

Mass public opposition to the hardliners strengthened the bond between Khamenei and the IRGC. Long dismissed as uncharismatic and uninspiring, a cult of personality began to form around the supreme leader as hardliners hailed him as the standard-bearer they would coalesce around to confront the reformist surge.

His supporters began to create a Khamenei-ism, depicting him as infallible and holy, God’s representative on Earth. The 2009 uprising over the disputed re-election of his then-adjutant, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, forced the hardliners, IRGC, and Khamenei to further rely on and bolster each other.

Raised in a strict and brutal household, Khamenei already had authoritarian tendencies, but they became much stronger.

“This is what happens when you live in a bubble where people are saying you are there by divine grace,” says Ansari. “You begin to believe it.”

Khamenei today is blessed with weak domestic rivals, a laughable foreign opposition, and control over a vast security force that has a presence in almost every country in the Middle East and can carry out operations abroad.

Under Khamenei, Iran has expanded its influence over Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and Afghanistan. He has made Iran the centre of Shia theology and power, making it the patron of 150 million adherents to the Islamic sect, using petro-dollars to co-opt the once semi-autonomous clergy and sideline those who resisted the authority of Tehran and Qom.

But though he has been a powerful key figure in the Middle East for four decades, he remains in large part a mystery.

Not a single serious English-language book has been written about him, and the ones in Persian are largely authorised hagiographies. He doesn’t attend international conferences unless they are in Iran. He doesn’t give interviews to local or international media, though he often holds forth to groups of scholars, artists, politicians and scientists.

Even the 2015 nuclear deal that his government negotiated with the US was done through intermediaries, and largely out of public view. Unlike President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, there was no photo op between President Barack Obama and Khamenei, or even the president, Rouhani.

“He loves to be secretive, and below the radar,” says Golkar. “That’s been his strategy for more than 30 years.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments