In the beginning there was a dispute over Hebrew Bibles...there still is

Israeli library in court over medieval manuscripts taken from Syria by Mossad 20 years ago

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Two decades after Israeli spies helped Syrian Jews take medieval Hebrew Bibles from Damascus to Jerusalem, Israel’s national library has asked an Israeli court to grant it custodianship over the manuscripts – a move that could spark an ownership battle over some of the Syrian Jewish community’s most important treasures.

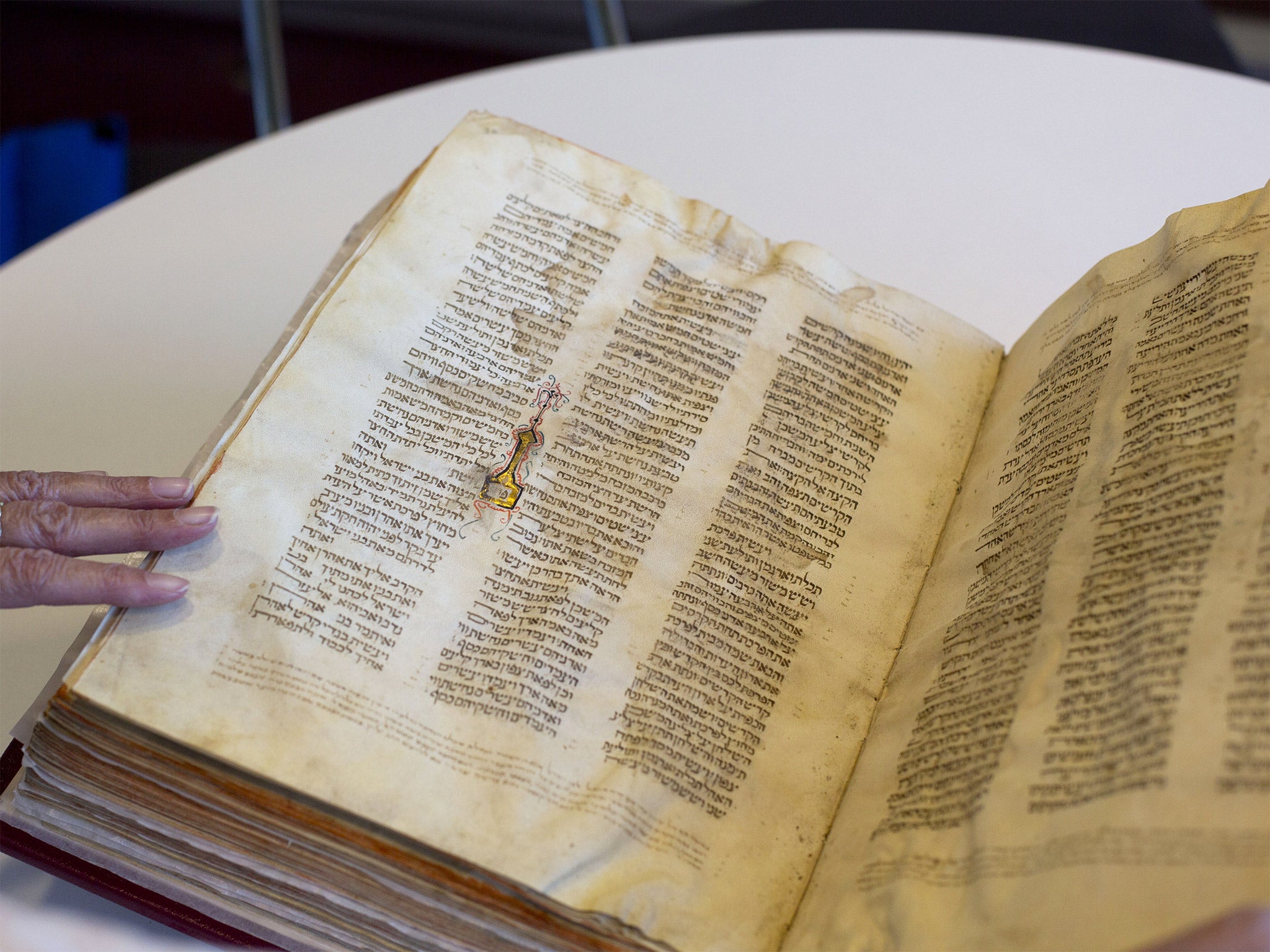

Known as the Crowns of Damascus, the nine leather-bound parchment books – some featuring micrography, or decorations made up of thousands of tiny letters , and gold-leaf illumination – were written mostly in Spain and Italy between 700 and 1,000 years ago. For hundreds of years, they were guarded in synagogues in Damascus, presented only on special occasions.

In the early 1990s, Syria lifted travel restrictions on Jews and many emigrated, but they were not permitted to take the manuscripts.

So, in a covert operation by the Mossad, eight of the manuscripts were spirited to Israel between 1993 and 1995. The ninth was smuggled out of Syria in 1993 with the help of a Canadian Jewish activist. Once in Israel, the manuscripts were entrusted to the national library for restoration and storage. Their existence there was kept secret for a decade, presumably not to draw the ire of Syria. The library already had two other Damascus Bibles in its collection, purchased in the 1960s and 1970s in private sales.

Details of the Mossad operation remain classified, but the man who helped organise it was Rabbi Avraham Hamra, the then-leader of the Damascus Jewish community. Shabtai Shavit, the Mossad director then, confirmed Mr Hamra’s involvement.

The existence of the Bibles was revealed in 2000 when they were exhibited at the Israeli President’s residence. And on Monday, the National Library of Israel went to court to formally ask the justice ministry to establish a kind of public charitable trust for the nine Crowns of Damascus.

According to the proposal, the manuscripts would remain in the library’s climate-controlled coffers and a steering committee, including Damascus Jewish immigrants, would oversee them. The Damascus Jewry Organisation in Israel, the main group representing Damascus immigrants, supports this. But Mr Hamra, who is not connected to that organisation, opposes the proposal and says he may challenge it in court. He argues the Bibles are Syrian Jewish cultural property, and that the library had promised to transfer them to a Syrian Jewish heritage centre in Israel he plans to build.

That promise, Mr Hamra says, appears in a catalogue from the 2000 exhibition co-sponsored by the library. The catalogue calls the manuscripts the “religious and spiritual treasure of the Syrian Jewish community” and says the Israeli library would safeguard them “until the establishment of a Syrian Jewish heritage centre in Israel.”

But Mr Hamra has not yet built the centre, and the library denies it ever promised him the manuscripts. It asked Mr Hamra to be a member of the proposed steering committee, but he declined.

“It is not my property, but it is the property of my community,” Mr Hamra said.

The proposed trust would enshrine the manuscripts as “owned by the Jewish people”, said Haggai Ben Shammai, the library’s academic director. “It cannot be transferred to anybody.” Mr Shammai said he is not worried about possible Syrian demands to return the Bibles, since they were never Syrian government property but belonged to Syria’s Jewish community.

There was no comment from authorities in Damascus, where few Jews remain.

The battle mirrors a famous tug-of-war over another Jewish manuscript from Syria: the 10th-century Aleppo Codex, considered the most ancient authoritative Hebrew Bible.

Like the Crowns of Damascus, the Aleppo Codex was safeguarded in a Syrian synagogue. A Syrian Jew fleeing persecution smuggled it to Israel, where it landed in the hands of the Israeli President in the 1950s.

Aleppo Jews in Israel took the Israeli government to court, saying the Bible was meant to reach their community. A trial lasted years and ended in compromise – a trusteeship led by an Israeli chief rabbi was established to oversee the Aleppo Codex.

Meir Heller, a lawyer for the national library, said the library is prepared to advertise its proposal in newspapers in Syria, Europe and the US to allow objectors to challenge the move in court.

AP

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments