Habib Essid interview: Tunisia's PM on why he believes his country's increasingly perilous position is the fault of Western powers

Exclusive: Nation has seen a crackdown of public freedom after twin massacres

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Habib Essid first served as a high official during the era of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, the dictator whose overthrowing and flight brought about the birth of the Arab Spring. Now, as then, a state of emergency exists in Tunisia.

In his office in the stately Dar El Bey building, a palace of white marble floors and elegant archways, the Prime Minister attempts to justify a recent crackdown of public freedom after the twin jihadist massacres at the Bardo Museum in Tunis and the beach resort of Sousse. “It’s to protect our young democracy,” he tells The Independent. “They can’t hold protests or go on strike, but they can express themselves in other ways. People can talk or write [whatever they like].”

The one-month state of emergency was introduced on 3 July, and has been extended until 2 October. This includes a ban on all demonstrations and strikes. Tunisia is struggling to maintain its much-hailed democracy, faced with Islamist threats on its border with war-torn Libya and an increasing threat from within. Twenty-two people were killed when three gunmen stormed the Bardo Museum on 18 March this year, most of them European tourists.

Then, in June, 30 Britons were killed when gunman Seifeddine Rezgui opened fire on Sousse beach. Both attacks were claimed by Isis. Mr Essid describes the attack at Sousse as a “barbaric act which has no justification”. He adds: “It’s a worldwide phenomenon, it doesn’t just concern one country alone.”

Mr Essid says the authorities are working with Britain, providing “information and equipment” to trace the network behind the gunman.

He says around 150 people have been arrested in connection with the attack, 15 of whom have been charged with “terrorism-related offences”.

In recent weeks there have been signs that the West may soon be forced to step in to the conflict in Libya, which has led to thousands of migrants attempting to enter Europe, fleeing a worsening conflict.

There have been reports of a military intervention in Libya by a coalition of British, French, American, Spanish, German and Italian forces, if rival Libyan factions can form a single unity government. “We have not been informed of [the possibility of intervention],” says Mr Essid, in a lengthy interview in his office, in the heart of the centuries-old Medina in Tunis. “We are against all military intervention in Libya.” The 65-year-old adds: “We consider that the current situation is the result of the [2011] intervention, which created chaos.”

Neighbouring Algeria, which has attempted to play a key role in mediating the Libyan conflict, would also likely be angered by the prospect of another Western intervention in a fellow North African country. There have, however, been several instances of foreign forces conducting air strikes in Libya, where Isis has obtained a foothold in several towns, including Sirte.

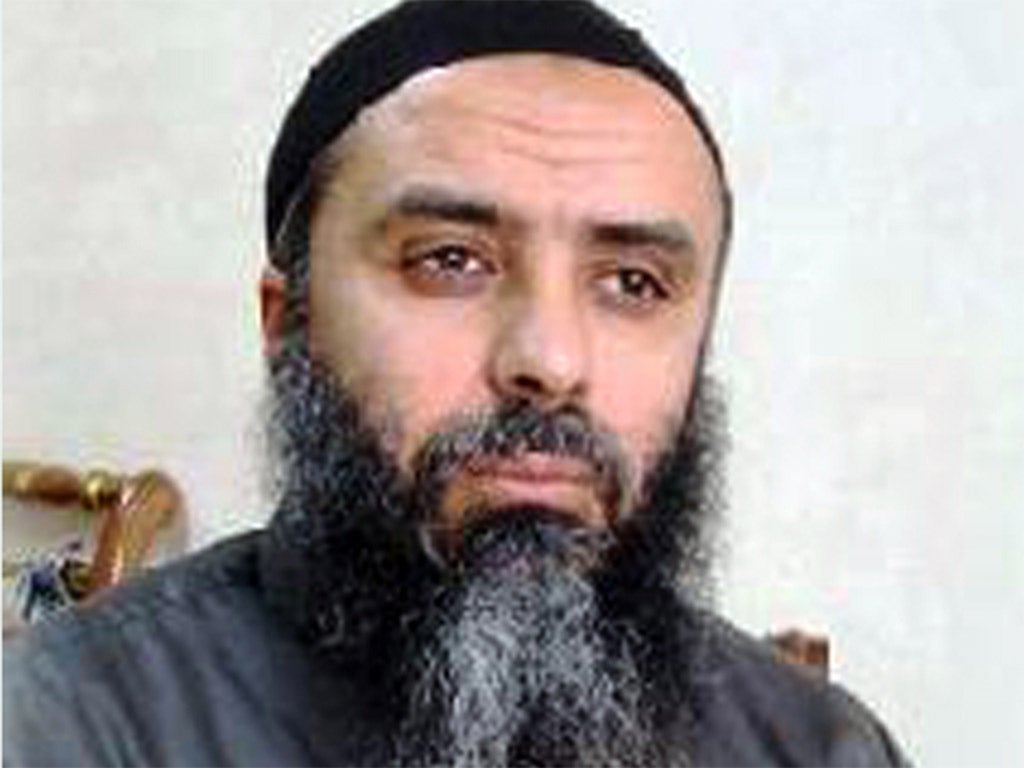

The most recent reported strike was the reported killing of Tunisia’s most notorious jihadist leader by the US. According to officials in Washington, Seifallah Ben Hassine, who went by the pseudonym of “Abu Iyadh”, was killed in mid-June, shortly after the Sousse attack.

Linked to al-Qaeda, he had established the now-illegal Ansar al-Sharia group in Tunisia in 2011. After fleeing to Libya, he is believed to have set up a network of training camps. Rather than calling for foreign intervention in Libya, Mr Essid says Western powers must help Tunisia from afar. “Terrorism isn’t a national problem. It has no borders,” he said. “Helping to fight terrorism in Tunisia means helping to defend themselves.”

Tunisian authorities have previously said the two gunmen who walked with apparent impunity through the Bardo Museum for several minutes, Yassine Laabidi and Hatem Khachnaoui, and Sousse gunman Rezgui, trained in Libya. Mr Essid says the Tunisians were collaborating closely with the British to gather more information on the Libyan training camps.

The Tunisian Prime Minister says Tunisia was sympathetic to the travel warning introduced by the British authorities after the attack at Sousse, despite the impact it has had on Tunisia’s tourism industry. “We have this problem of the travel warning, which we understand perfectly is the act of a sovereign state, which has a responsibility to protect its citizens,” he adds. “[But] while we didn’t dispute this decision, it’s had a negative impact [on the Tunisian economy].”

Mr Essid’s government has faced criticism from civil society and NGOs for a series of initiatives introduced in the wake of the Bardo and Sousse massacres, viewed as moving to crack down on political dissent. Then came the introduction of the long-stalled anti-terrorism law, approved on 25 July. The tiny minority of MPs who opposed it found themselves the target of indignant editorials in the national media, as have eight NGOs, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.

“By what right, did a collection of eight foreign NGOs… publish a joint communique calling the new anti-terrorist law a ‘threat to human rights’, calling for ‘amendments to the Tunisian Penal Code’?” read an editorial in daily newspaper La Presse. Under the new law, Tunisian police will have the right to interrogate suspects without a lawyer for up to 15 days, witnesses can give testimony anonymously and courts can hold closed hearings.

It was amended, however, protect journalists’ right to confidentiality, to protect lawyers and doctors from being prevented from working with clients accused of terrorism, and to guard against unauthorised government surveillance. The NGOs said the law allows for “disorderly protest” to be deemed “terrorist”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments