65 journalists have been killed in Syria since the war began - so how do reporters stop themselves from becoming the story?

There's never been a more dangerous time to be a reporter; and there's never been a more dangerous place to report from than Syria

On 19 April, four underfed men were found in a field in a no man's land on the Turkish border with Syria. They were blindfolded and handcuffed and one had a long grey beard. It was quickly discovered that they were four French journalists – Nicolas Hénin, Pierre Torres, Edouard Elias and Didier François.

They had been held for more than 10 months by a radical Muslim group, Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (Isis), the objective of which is to establish an Islamic state in the northern Syrian land which it has pried from Bashar al-Assad's regime.

Being captured by Isis is the nightmare of all journalists reporting on the Syrian civil war. On 31 March, Isis released Javier Espinosa, a reporter for the Spanish paper El Mundo, and a photographer, Ricardo García Vilanova. There are believed to be 30 more journalists still in captivity in Syria. While there is news from some, others appear to have disappeared from the face of the earth.

“They came to her door and took her away,” says the friend of one Syrian journalist who disappeared in February. A mother of small children, she had been investigating war crimes by both sides. “We have had no news since.”

In addition to Isis, other radical groups are holding some reporters, the Syrian government others. Most news organisations are wary of revealing details of the captives for fear that it will compromise negotiations for their release.

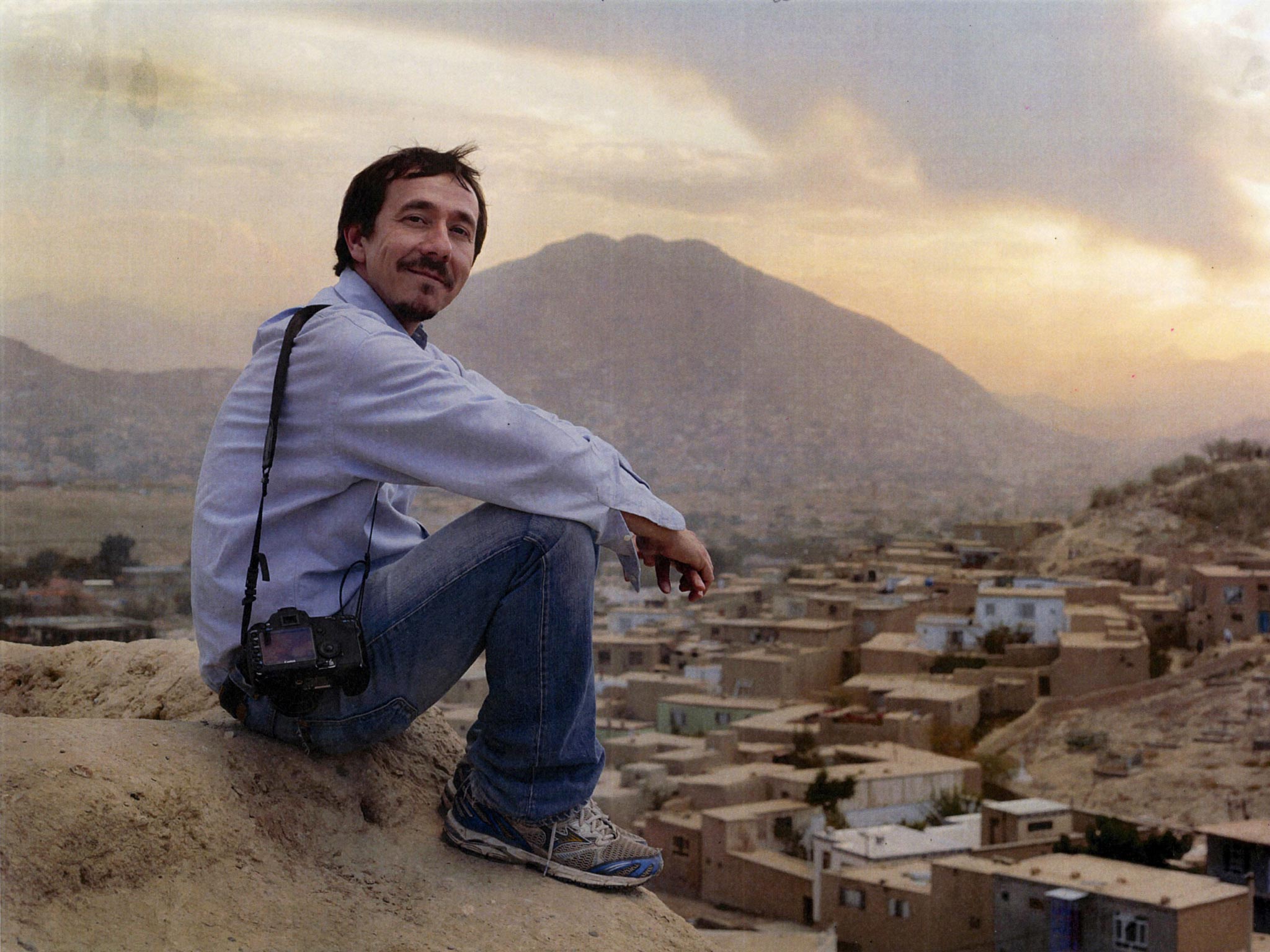

The freed French journalist with the bushy beard, Didier François, 53, a reporter for the French radio station Europe One, had covered many conflicts before he was kidnapped, including the wars in Bosnia for the French daily Libération.

One time, in Sarajevo, François darted in the middle of gunfire to rescue a British photographer, Tom Stoddart, who had been badly injured and could not move. Stoddart later credited François with saving his life.

Later, François reported from Kosovo, Chechnya, Afghanistan, Africa and other danger zones. Even in Chechnya, where warlords were at one point decapitating hostages and posting their heads on spikes, the Frenchman managed to stay safe. It took the Syrian war to land him in extended captivity.

Although François and the others were not tortured as earlier victims had been, they were chained together, not given enough food or water and kept in darkened rooms and cellars for most of their 10 and a half months' captivity. François said it was “a great joy and an immense relief, obviously, to be free. Under the sky, which we haven't seen for a long time, to breathe the fresh air, to walk freely”.

One can only trust that other hostages, including the American James Foley, missing since Thanksgiving Day in November 2012, have not lost hope. Austin Tice, another American, has been missing since August 2012.

Syria is the most dangerous country in the world, a feeding ground for terrorist groups abducting reporters, aid workers and anyone else who dares to cross the border. At least 65 journalists have been killed since the conflict began.

“The emergence of hard-line Islamist fighters has made Syria coverage even more dangerous for the press,” explains Joel Stein, of the Committee to Protect Journalists.

“While other armed opposition groups, especially the Free Syrian Army, have courted international public opinion and facilitated the work of the press, the hard-line factions have no use for international journalists and no interest in shaping Western public opinion. Journalists are simply bargaining chips.”

John Owen, a professor of journalism at London's City University and chairman of the Frontline Club, an association for war reporters, says that abducting journalists may be “barbaric”. But, he says, “there is an even greater danger, which lies at the very root of reporting the truth. [Kidnapping] has also succeeded in making Syria so dangerous to report on that only rarely now can journalists get any safe access to bear witness to this humanitarian disaster.”

Read more: Ransom rumours after French hostages go free

Syria conflict: Four French journalists freed

Spanish journalists freed after Syrian kidnap ordeal

Reporters Without Borders (RWB), the media watchdog, says that more than 87 journalists have been kidnapped worldwide, many in Mexico, where reporting the drug wars means risking being kidnapped, tortured and killed. In former conflicts (other than the Lebanese civil war in the 1980s), it was rare for journalists to be used as bargaining tools. But the Syrian war has reached new heights in abduction.

Some manage to escape – climbing through windows or even fighting their way out. In 2012, the BBC's Paul Wood and his crew escaped captivity in Syria, as did NBC's Richard Engel and his team. Others have governments that do not give up. Whether the Spanish or French government (or both) paid kidnappers to free the most recently-snatched reporters is unclear. The French have denied it, although they allegedly have paid to release other hostages in the past, including those held by the terrorist group Abu Sayyaf in the Philippines.

The American and British governments repeatedly say that they will never negotiate with kidnappers and will not pay ransoms. As a reporter covering Chechnya and other war zones in the 1990s for News International, I was repeatedly told that if I was kidnapped, my government would not barter with kidnappers. Nor did my expensive war insurance – a bone of contention for reporters – cover kidnapping. “Kidnap insurance turns you into a walking ATM,” one of my editors told me. “We don't sanction it.”

According to a study by Dr Anthony Feinstein, a Canadian psychiatrist who writes about the effect of trauma on war reporters, more than a fifth of journalists had no insurance of any kind while covering the Syria conflict.

Some families of kidnapped reporters make sure the world does not forget that their relatives are missing. Foley's family keeps a blog and has reached out to reporters to approach their contacts for information.

Governments are usually aware of where their citizens are being held. “The US State Department apparently knew exactly where we were throughout the time we were captured,” says one of three hostages held during the Nato-led bombing campaign in Libya in 2011. “They knew down to the house we were kept in.”

Is there any way to prevent an abduction? “Kidnappings are based on financial or political motives,” says Darren White of the UK security group Dragonfly. “And they generally follow a process that is very similar to the attack cycle. There is target selection, planning, deployment, attack, escape and exploitation.”

White says there are “almost always” telltale signs that the abduction process is in motion prior to the actual kidnapping. Which translates as: keep your eyes open. “In retrospect, almost every person who is kidnapped has either missed or ignored an indication or warning,” he says.

During the “hostile environment courses” that many war journalists now undergo, there are extensive kidnapping workshops teaching them how to avoid situations that might place them at risk: always be met at an airport if you are travelling to an unknown location; know your route; do your research. They are also taught what to do if kidnapped – when is the best time to try to escape? – and how to survive if you are caught and abused. UN field workers, also frequently targeted by kidnappers, are even advised which floors of hotels are the safest.

RWB recently began teaching reporters in Senegal, France, Tajikistan, Tunisia and the US how to encrypt data as a measure to protect them when they are in the field. “If you do not encrypt your data and communications, you take the risk that everybody knows where you are,” says Christophe Deloire, the group's director. “And they can come and kidnap you.” Another tactic used by reporters is a virtual private network such as WiTopia, which gives a false location, indicating that they are working from, say, Las Vegas or Dallas when they are in fact working inside Syria.

Then there is the trauma suffered by those abducted. One reporter who was kidnapped for more than a year during the Lebanese civil war says he still has nightmares. “I always hated seeing those films about kidnappers and their hostages and how they became close, even friends,” he says. “It's a lie. I hated my jailer, and he hated me.”

Others advocate safer practices. “We have to consider the lessons learned,” says Deloire. “One of the first things Didier did when he got off the plane was to say to the heads of Europe, 'We have to think of what happened to me. We have to analyse and improve so this does not happen to others. We need to share the experiences so that we can learn... ' ”

With all the risk to reporters, most news organisations have chosen to cover Syria from afar. Some hire local stringers, aware that they are losing their objectivity by hiring activists. Others get Damascus-issued (ie, from the Assad government) visas, which are usually given only to those who will toe the line.

“The risks are not only to journalists, but also to their sources, who may face reprisals or threats for giving interviews,” says Emma Daly from Human Rights Watch. “This is true whether the meetings are conducted face-to-face or via phone or internet.” Meaning that the people whom reporters interview, even on Skype, can be subject to harassment, incarceration, or worse.

The price of getting the truth out can be high for those who dare to risk their lives on the front line. “It was a long time not to see the sun,” said François after his release. “It was really a black hole.”

©Newsweek

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments