How anti-immigrant anger threatens to remake the liberal Netherlands

Clashes between Dutch police and Turkish protesters this weekend exposed dangerous tensions ahead of tomorrow’s election, in which the far-right Freedom Party is promising to shut borders, close mosques and wreck the EU. How did a famously tolerant society come to this?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Xandra Lammers lives on an island in Amsterdam, the back door of her modern and spacious four-bedroom house opening on to a graceful canal where ducks, swans and canoes glide by. The translation business she and her husband run from their home is thriving. The neighbourhood is booming, with luxury homes going up as fast as workers can build them, a quietly efficient tramway to speed residents to work in the world-renowned city centre, and parks, bike paths, art galleries, beaches and cafes all within a short amble.

By outward appearances, Lammers is living the Dutch dream. But in the 60-year-old's telling, she has been dropped into the middle of a nightmare, one in which Western civilisation is under assault from the Muslim immigrants who have become her neighbours.

“The influx has been too much. The borders should close,” said Lammers, soft-spoken with pale blue eyes and brown hair that frames a deceptively serene-looking face. “If this continues, our culture will cease to exist.”

***

To Europe's powers that be, the threat looks dramatically different but no less grave. If enough voters agree with Lammers and support the far right in elections here on Wednesday and across the continent later this year, then it's modern Europe itself - defined by cooperation, openness and multicultural pluralism - that could come crashing down.

The stakes have risen sharply as Europeans' anti-establishment anger has swelled. In interviews across the Netherlands in recent days, far-right voters expressed stridently nationalist, anti-immigrant views that were long considered fringe but that have now entered the Dutch mainstream.

Voters young and old, rich and poor, urban and rural said they would back the Geert Wilders-led Freedom Party - no longer the preserve of the “left-behinds” - which promises to solve the country's problems by shutting borders, closing mosques and helping to dismantle the European Union.

“They've found a very powerful narrative,” said Koen Damhuis, a researcher at the European University Institute who studies the far right. “By creating a master conflict of the national versus the foreign, they're able to attract support from all elements of society.”

Along the way, Europe's old assurances have been swept aside. The far right may exist, the continent's political establishment has long told itself, but a virtuous brew of growing economic prosperity, increased cross-border integration and rising education levels would blunt its appeal. Most important all, the pungent memory of the nationalist right's last turn in power would keep it from ever gaining control in Europe again.

But in 2017, every one of those assumptions is being challenged - perhaps even exploded.

***

After the jolts of Brexit and Donald Trump last year, continental Europe is bracing for a possible string of paradigm-rattling firsts in its postwar history.

In France, far-right leader Marine Le Pen has a credible shot at a triumph in spring presidential elections. In Germany, an anti-immigrant party appears poised to win seats in the national parliament this fall. And here in the Netherlands, a man convicted only months ago of hate speech could wind up on top when votes are counted in next week's national elections.

At first glance, the Netherlands - a small nation of 17 million that has long punched above its weight on the global stage through seafaring exploration and trade - seems an unlikely setting for a populist revolt.

Unlike in France, where the economy continues to stagger nearly a decade on from the global financial crisis, the indicators in the Netherlands are broadly positive: falling unemployment, healthy growth and relatively low inequality. By most measures, the Dutch are some of the happiest people on earth.

And unlike Germany, where Angela Merkel opened the country's borders to a historic influx of refugees in 2015, the Netherlands has been relatively insulated from mass immigration. Compared with its neighbours, the Dutch took significantly fewer asylum seekers during the refugee crisis, and much of the country's non-native population settled in the Netherlands decades ago.

***

Those differences make it all the more surprising that the far right's message resonates here and hint at just how difficult it could be to halt the global populist wave.

For much of the past two years, Wilders' Freedom Party has led the polls, though it has recently dropped into a virtual tie with the ruling centre right.

Because of the deeply fragmented nature of Dutch politics - there will be 28 parties on the ballot on Wednesday - the Freedom Party could come out on top with just 20 per cent of the vote. Even if it does, it is considered extremely unlikely that Wilders would end up governing, because other parties have spurned him.

But he has already had an outsize influence, forcing rival politicians - including the prime minister, Mark Rutte, - to shift their policies and rhetoric in his direction.

***

To many Wilders supporters, the overall picture of a growing economy with a comparatively small number of recent immigrants is beside the point. Their reasons for backing the platinum-haired politician - who refers to Moroccans as “scum” and advocates a total ban on Muslim immigration - run much deeper.

“The main issue is identity,” said Joost Niemöller, a journalist and author who has written extensively on Wilders and is sympathetic to his cause. “People feel they're losing their Dutch identity and Dutch society. The neighbourhoods are changing. Immigrants are coming in. And they can't say anything about it because they'll be called racist. So they feel helpless. Because they feel helpless, they get angry.”

And today, that anger can be found far beyond the poorer, less-educated, working-class areas where Wilders and his party first gained substantial support.

“I hear it on the tennis court and at the golf club. People don't want immigrants,” said Geert Tomlow, a former Freedom Party candidate who fell out with Wilders but still sympathises with many of his positions. “One-third of Holland is angry. We're angry. We don't want all these changes.”

That is true even in places where little seems to have changed.

***

Teunis Den Hertog, a 34-year-old small-business owner, lives in a pastoral town that he said is virtually untouched by immigration. “I've heard there's a Turkish man who lives here - but just outside the town, thankfully,” he said.

Nonetheless, Den Hertog said he wants the government to close the country to new arrivals and reestablish compulsory border checks for the first time in decades.

“You can see a vehicle coming with a lot of men with dark skin and pick them out,” said Den Hertog, who grew up poor and one of nine children but now earns enough to afford a comfortable, suburban-style house for his family of four. “Otherwise, it's just too dangerous.”

Den Hertog said he typically avoids the country's diverse, cosmopolitan cities. But Wilders supporters exist there, too, as Lammers - the Amsterdam island resident - can attest.

University-educated, financially successful and raised in the culturally progressive firmament of the Netherlands' biggest city, Lammers had long staked her ground on the left. Her father was a regional mayor from the Labour Party, and she identified as a supporter well into adulthood.

“I was very politically correct,” she said. “I believed in the social experiment.”

It was a move up the social ladder that precipitated her shift across the political spectrum.

In 2005, she and her husband bought their home in the Amsterdam neighbourhood of IJburg, an innovative development built on a cluster of artificial islands.

Like many who moved there, Lammers and her husband did so because the area offered bigger houses at lower prices than could be found in the crammed city centre. And at first, it was everything they had hoped.

“It had a village feeling. Everyone knew each other. They put a temporary supermarket in a tent,” she recalled. “It was cosy.”

But then came a surprise. Families of Moroccan and Turkish origin started moving in, part of a social program to dedicate 30 per cent of the development's housing to people on low incomes, the disabled or the elderly.

Suddenly, she said, white Dutch residents had to share their streets, gardens and elevators with Muslim women wearing headscarves and men sporting beards. Crime, noise and litter soon intruded on her urban idyll, she said.

The newcomers generally spoke Dutch, and many seemed to work. But she faulted them for “not integrating,” the evidence of which she said could be found in their traditional dress and attendance at a modest, storefront mosque.

She suggested they try church instead, though Lammers said she does not attend. (“Sometimes on Sunday I watch American church on the television,” Lammers said. “They're very opposed to Islam. I like that.”)

***

If the newcomers have hurt her neighbourhood's desirability, it's not apparent in the home prices, which have sharply risen. Nor is it visible on the streets, which are clean, tidy and, on a mild late winter's day, filled with children of various ethnic backgrounds happily riding scooters and bikes. But Lammers remains bitter.

“You think you're going to live in a well-to-do neighbourhood,” she said. “But you end up living in a so-called black neighbourhood because of the socialist ideology.”

Among the beneficiaries of that ideology is one of Lammers' friends, Ronald Meulendijks, a 44-year-old who has been living on full-time medical disability since he was 29.

The government pays him the equivalent of $1,000 (£818) a month and provides him with a steep discount on a light-filled, three-bedroom apartment in the heart of IJburg - benefits he said he deserves as a native-born Dutchman with a long pedigree.

***

“My whole family of seven generations paid taxes,” he said.

Muslim immigrants and their children, by contrast, are undeserving, he said.

“When I see all the refugees getting everything for free, I get very angry. I want to throw something at the television,” said Meulendijks, who dotes on his pair of chow-chow rescue dogs and serves visitors to his art-filled apartment copious tea and strawberry pie. “A government has to treat its own people correctly before accepting new ones. First, you must take care of your own.”

And if the government fails, Meulendijks has dark visions of what's to come.

“I think Holland will need a civil war,” he said, “between the people who don't belong here and the real people.”

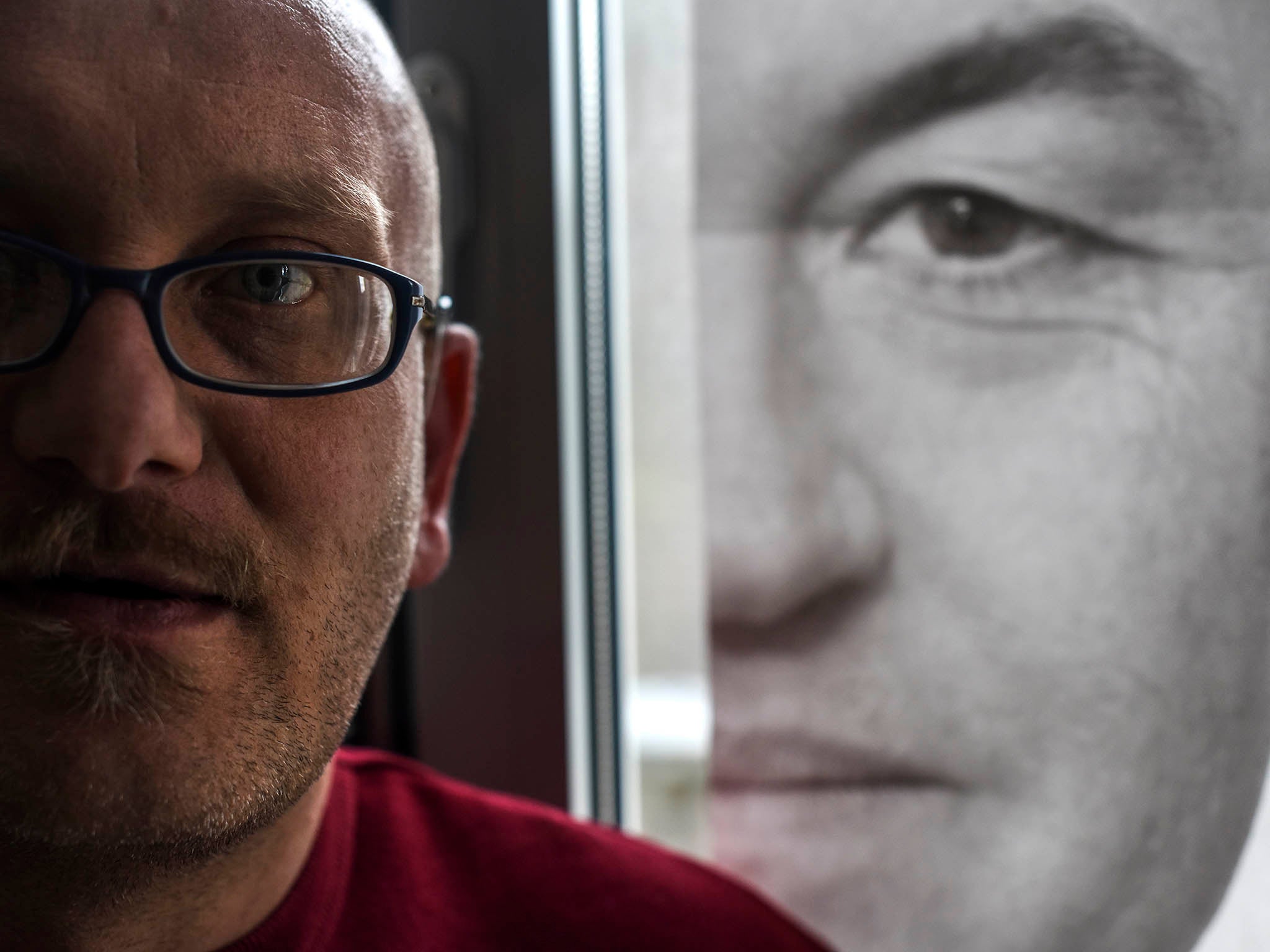

To drive home the point, Meulendijks has decorated his panoramic windows with five large posters bearing the face of Wilders and his party's campaign slogan: “The Netherlands is ours again.”

A pronounced nick in the glass - the result of a carefully aimed rock - suggests not everyone in the neighbourhood agrees with Meulendijks' clash-of-civilisations world view.

Neighbours said they did not recognise the grim vision of IJburg that Lammers and Meulendijks described.

“Which country you come from or which religion you have, it doesn't matter here,” said Iris Scheppingen, 41, a resident for the past decade who is raising three children in IJburg. “The children all play together.”

At a nearby halal pizza restaurant - one of IJburg's few businesses that explicitly cater to Muslim customers - the owner said the area was safe and quiet. He said he had never noticed a cultural clash.

“Nice people here,” said 49-year-old Farhad Salimi as his staff of young kitchen workers slung pies and sprinkled toppings. “Everyone comes here for pizza. Immigrants. Dutch people. Everybody. We don't have problems.”

The world, however, was a different story.

A refugee from Iran who moved to the Netherlands nearly 30 years ago, Salimi said he had seen what religious zealotry and the politics of exclusion did to his native land.

Now, the grey-haired Salimi fears, it is happening across the West, even in the peaceful and prosperous country that had so enthusiastically welcomed him.

The politicians are exploiting divisions, turning people against one another for their own gain, he said. Extremism is rising. Where will it end?

“Everywhere,” he said solemnly, “is messed up.”

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments