HMS Erebus video: Divers conduct live tour of Sir John Franklin's recently discovered flagship

Canadian divers presented tour of wreck - 11 metres beneath the surface of Arctic Ocean

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Almost 170 years after it disappeared – and just seven months after it was found – the flagship from Sir John Franklin’s ill-fated expedition to discover the North West Passage has been shown to the world.

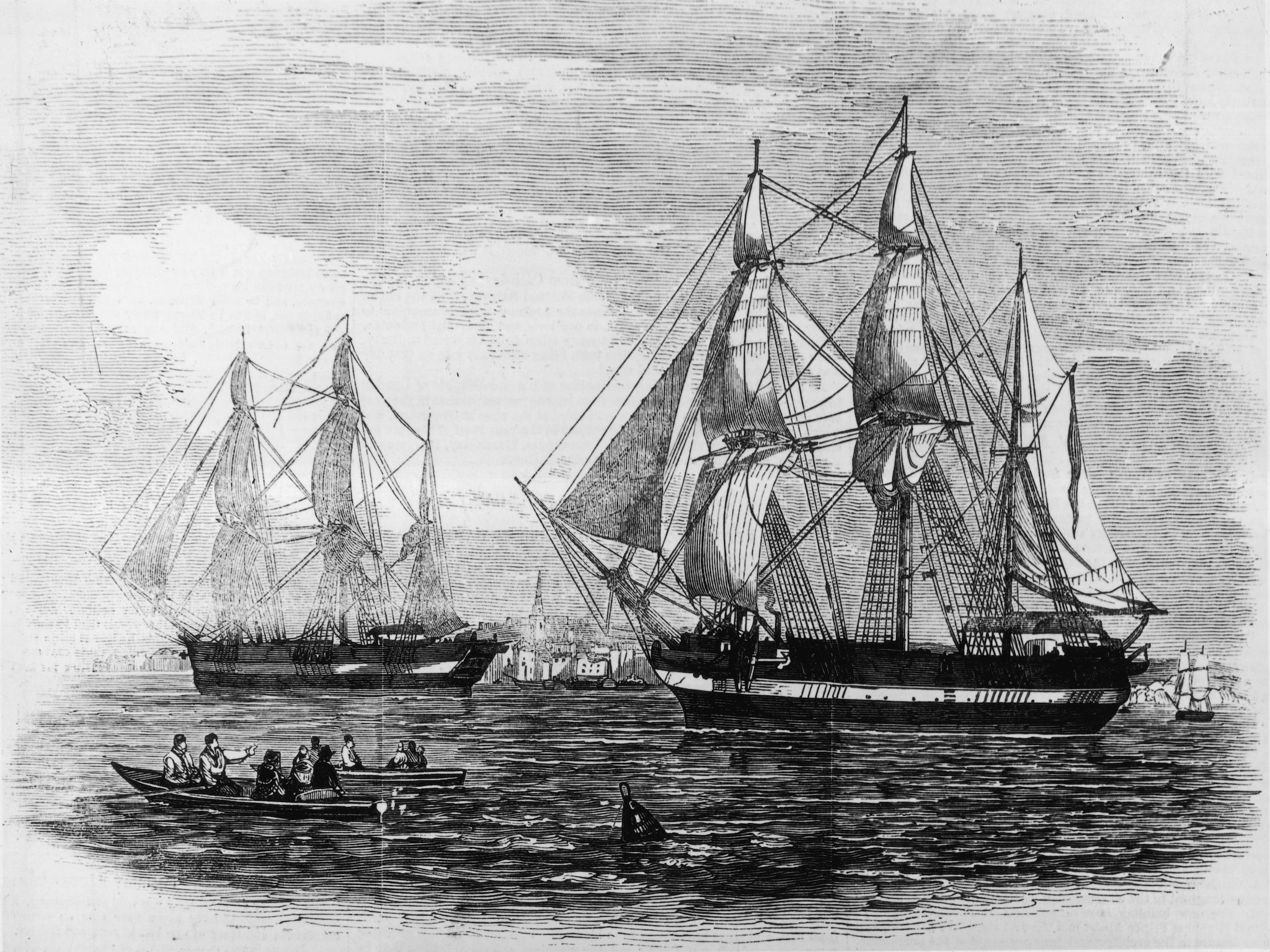

HMS Erebus was one of two ships that went missing in the Canadian Arctic with the loss of Franklin and his entire 128-strong crew after becoming trapped in ice, probably in 1846. Subsequent searches found some remains and documents that suggested Franklin perished in the summer 1847.

Despite extensive searches, several funded by Franklin’s widow, no trace of the HMS Erebus was discovered until Canadian officials announced last September that the ship had been located.

On Thursday, Parks Canada, a government agency, hosted a live presentation by archaeologists and ice divers who descended 11 metres beneath the frigid waters of the Queen Maud Gulf.

“We have a real treat for you,” said diver Ryan Harris, as he led a tour of the wreck. “You’re going to be the first people to see this.”

Amid the kelp – and in between the sound of his breathing - Mr Harris pointed out two brass 6lb cannons, the tiller and quarter deck of the HMS Erebus, “where the senior officers would have sat”.

The footage subsequently released suggests that Franklin’s ship is remarkably well preserved, with the a sheared off main mast and some of the deck structures still intact. Divers recovered a large brass bell from vessel in November.

In the days before the Panama Canal, Franklin had been leading an expedition to try and find the so-called North West Passage, a route to the Pacific that would have saved sailors the time and danger of navigating via Cape Horn.

By no small irony, as a result of climate change and reduced sea ice, some of the routes that were shut off to Franklin, are now open to long-distance vessels.

An early search party found a note at Victory Point on King William Island recounting how both ships became trapped in the Arctic ice in 1846. According to the note, Franklin died the following year, on June 11 1847.

Three bodies linked to the expedition that were discovered in the 1980s were found to have a high lead content, and many believe the 129 men were unintentionally and unknowingly poisoned by lead from their poorly soldered tin cans.

No trace of Franklin has been found. His wife, Lady Jane Franklin, paid for several of the 20 or search expeditions that were launched and commissioned a bust that sits in Westminster Abbey.

She was also the author of the words to Franklin's Lament, a song made popular in the Sixties by the folk singer Martin Carthy.

"We were homeward bound one night on the deep,

Swinging in my hammock I fell asleep

I dreamed a dream and I thought it true

Concerning Franklin and his gallant crew."

The search for the sister ship of the Frankin's flagship, HMS Terror, is still continiung.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments