The war in Ukraine is crushing thousands of elderly Japanese people

In the disputed Northern Territories of Japan, the war has crushed people’s hopes of ever seeing their homeland again after Russia broke off negotiations, write Michelle Ye Hee Lee and Julia Mio Inuma

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Soviet soldiers barged into Hirotoshi Kawata’s home on 4 Sept 1945, searching for hidden Japanese soldiers and valuables. Kawata, then 11, remembers understanding only two words they said: tokei, or wristwatch; and sake, which they went on to loot from the home.

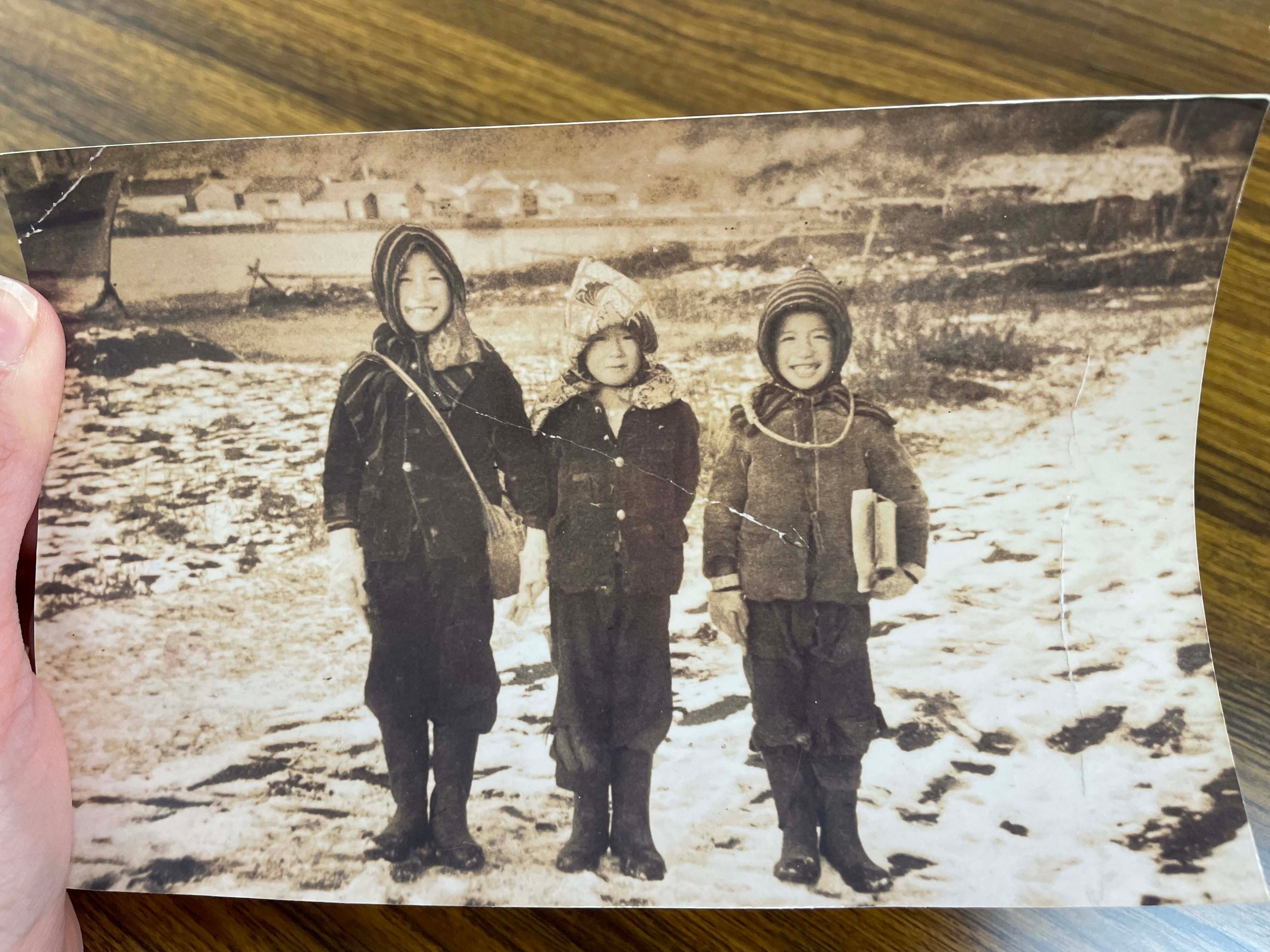

It was the beginning of the Soviet takeover of a resource-rich chain of islands in northern Japan, to the terror of families who had thought that the worst of the war was over after Japan’s surrender. Japanese citizens were soon forbidden from working or moving freely, and women and children were detained for forced labour.

Many families fled on boats in the middle of the night, rowing at first until they were far enough from the coast to turn on their engines. Kawata’s family was among thousands displaced during that time.

“All these years later, I still can’t forget everything I saw right before my eyes,” Kawata, 87, says. Now, “seeing the Ukrainians... it just hits so close to home. It doesn’t seem like something happening in the distance.”

Thousands of miles from Ukraine, in this city in the far northeast of Japan where many of the roughly 17,200 former residents of the Northern Territories resettled, the Russian invasion and the plight of millions of Ukrainian refugees resonate deeply.

The war has crushed their hopes of ever seeing their homeland again after Russia broke off the negotiations over the islands in response to Japan’s sanctions on Russia for invading Ukraine.

For these former residents, whose average age is nearly 87, the hope of returning home in their lifetimes has vanished.

In Nemuro, it’s hard to travel a few blocks without seeing a massive statue or sign demanding, in uncharacteristically forceful Japanese language: ‘The Northern Territories, give it back!’

“The only ones left to tell these stories are just the recollections of some fifth-graders. The rest have all passed away, unable to share their stories,” says Hiroshi Tokuno, 88, who fled Shikotan island at the age of 13.

For years, under former prime minister Shinzo Abe, Japan sought to improve relations with Russia and to prioritise the peace treaty and territorial settlement in an effort to make Moscow a strategic partner and keep it from drawing closer to China. When Russia annexed Ukraine’s Crimea region in 2014, concern over negotiations for the islands shaped Abe’s tepid response.

But in a dramatic turn away from its years of pursuing rapprochement with Russia, Japan has imposed wide-reaching economic sanctions in response to the invasion of Ukraine. Although negotiations had stalled since 2020, Moscow said last week that it had no intention of returning to talks and planned to end visa-free trips by Japanese citizens to the islands. It also threatened to withdraw from joint economic projects there.

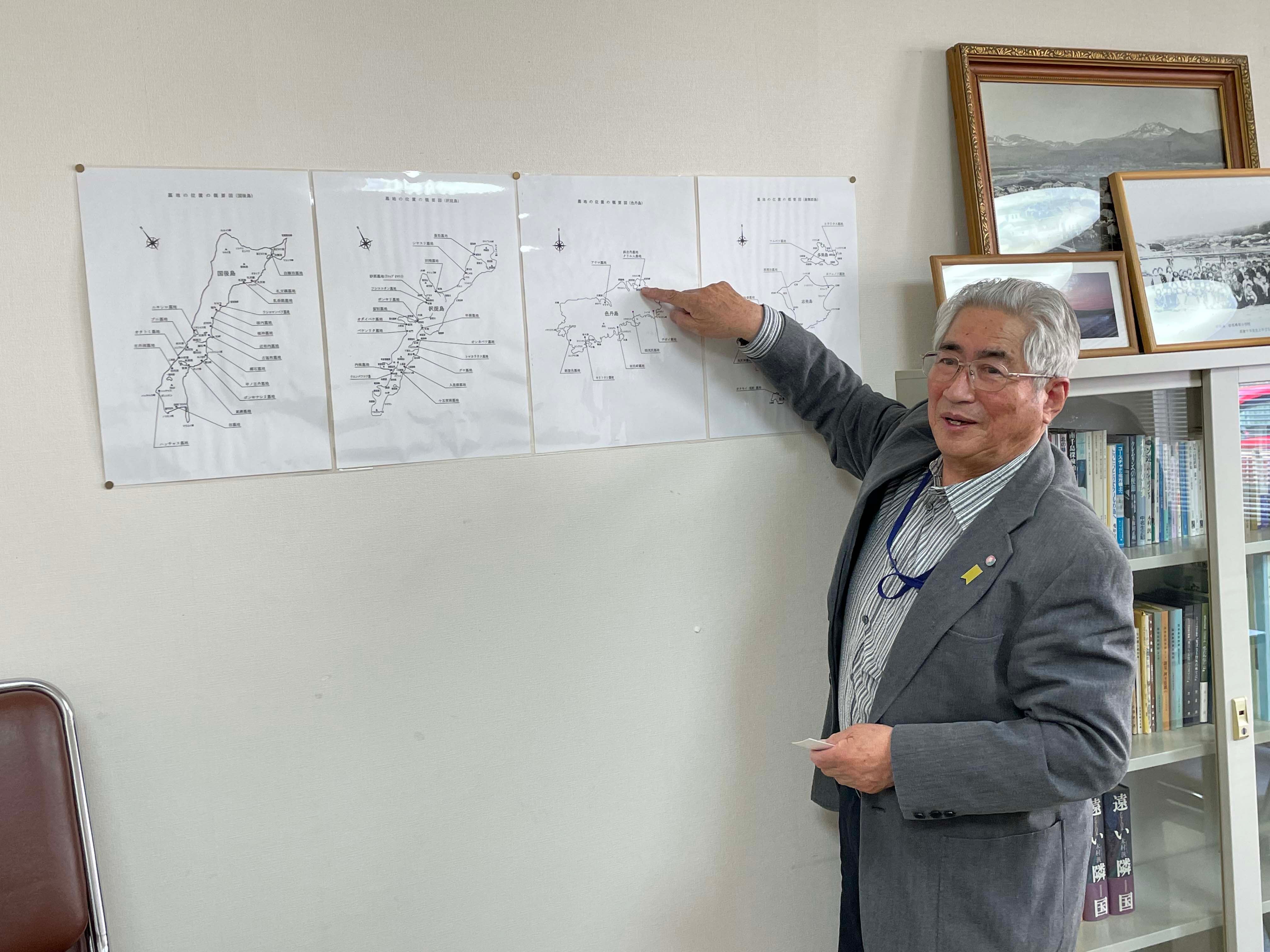

What Japan calls the Northern Territories – the islands of Kunashiri, Etorofu, Habomai and Shikotan – lie off the coast of Hokkaido, and some of them are visible from Nemuro on a clear day. They were part of Japan before the Second World War, but soon after the country surrendered in August 1945, the Soviet Union claimed the islands, which it called the Kuril Islands.

These volcanic islands southeast of Russia’s Sakhalin Island separate the Sea of Okhotsk and the Pacific Ocean, and are at the heart of post-war Russo-Japanese relations. The two countries made a joint declaration in 1956 ending the state of war between them, but have not signed a peace treaty. That has been awaiting a resolution of the dispute over the islands.

From Japan’s perspective, the Soviet seizure of the islands was a betrayal, because Japan had already surrendered, and the islands had been Japanese territory since the first treaty between the Russian empire and the empire of Japan in 1855, says James Brown, an expert in Russo-Japanese relations at Temple University’s campus in Tokyo.

For Russia, the islands are its rightful territories, obtained in exchange for joining the United States against Japan in the Second World War. Giving up the islands is considered a betrayal of Soviet soldiers and citizens as well as Russia’s Second World War legacy, Brown says. The islands are also of strategic interest to Russia, because they make it easier for Moscow to get its ships into the Pacific Ocean from the Sea of Okhotsk, and have valuable natural resources, including a rare-earth metal used in aerospace construction.

Tokyo and Moscow have held peace negotiations on and off since the 1956 declaration, but there has not been any significant movement. Unlike Japan’s territorial disputes with China and South Korea over largely uninhabited islands, the scale of the dispute with Russia is different, because the islands are bigger (Etorofu is nearly 2,000 square miles) and thousands of people’s lives are directly affected.

In Nemuro, it’s hard to travel a few blocks without seeing a massive statue or sign demanding, in uncharacteristically forceful Japanese language: “The Northern Territories, give it back!” Road signs and street names are written in Japanese and Russian, for the benefit of the Russian fishermen who do business in Nemuro.

Here, Russia’s announcement of its withdrawal from negotiations carries consequences. It prevents the former residents from visiting the graves of relatives on the islands. It also ends cultural visits between the islands’ Russian residents and Japanese citizens, who hoped that the two populations could one day co-exist if the dispute were ever resolved.

“It is extremely unfair and unacceptable, undermining the efforts of the residents of both countries who have been working hard to promote an exchange,” said Hokkaido governor Naomichi Suzuki in response to Russia’s announcement.

With Russia considering shutting down its economic agreement with Japan, the fishing industry is also on edge, because it relies on the waters between Japan and Russia. This area, where 3 million tonnes of fish and other seafood are caught annually, is considered one of the best places on the planet for fishing.

Fewer than 5,500 former residents of the Northern Territories are still alive. They are clear-eyed about what Japan’s tougher response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine means for the future of the negotiations over the islands, but some still support Japan’s standing up to Russia. At the museum in Nemuro dedicated to the dispute, residents and visitors have left messages attacking Russian president Vladimir Putin and expressing solidarity with Ukraine.

Some residents say they hope to see prime minister Fumio Kishida take a tougher approach with Russia to resolve the Northern Territories dispute.

“What Russia is doing in Ukraine, trying to change the status quo by force, can never be justified,” says Yasuji Tsunoka, 84, who was 8 when Soviet forces took over the tiny island of Yuri, a part of the cluster of Habomai islets on which there were 70 homes.

“Kishida made strong sanctions, and we understand this. But we want now, more than ever, for negotiations to be direct and strong, without trying to constantly be sensitive of Russia,” he says. “The situation in Ukraine is once again an issue of territory, just like the northern islands with Japan.”

After the Soviets took over the islands, some Japanese families remained for a few years, living alongside the Soviet families that had moved there. Tokuno recalls attending school with Soviet children, and his experience was later turned into an animated film for children called Giovanni’s Island.

But eventually, to make room for Soviet citizens, Japanese residents were displaced from their homes and pushed into sheds and horse stables. By October 1947, all Japanese remaining in the Northern Territories were taken off the islands in Soviet ships. That group included Tokuno, who recalls that they first withstood gruelling conditions in Sakhalin before making it to Nemuro. Some died on the journey.

It wasn’t until 1964 that Russia and Japan agreed to allow limited numbers of humanitarian trips to the islands so that former residents could visit their relatives’ burial sites.

The former residents say they hope future Japanese generations, as well as US leaders, will take up the fight.

“We will continue sharing the movement with the next generation to keep it going for as long as it takes,” Tsunoka says. “Japan must never stop.”

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments