Valeriy Lobanovskyi defined what it is to be Ukrainian, not Russian

In 1986 a Ukrainian manager led a mostly Ukrainian team to the world cup under the USSR flag, he is now a symbol to a culture under attack, writes Simon O’Hagan

Through the centre of Kyiv runs a wide boulevard called Lobanovskyi Avenue. It was here that a Russian shell struck an apartment building during the first two days of the invasion of Ukraine, providing one of the most vivid images so far of the horrors unleashed by Vladimir Putin.

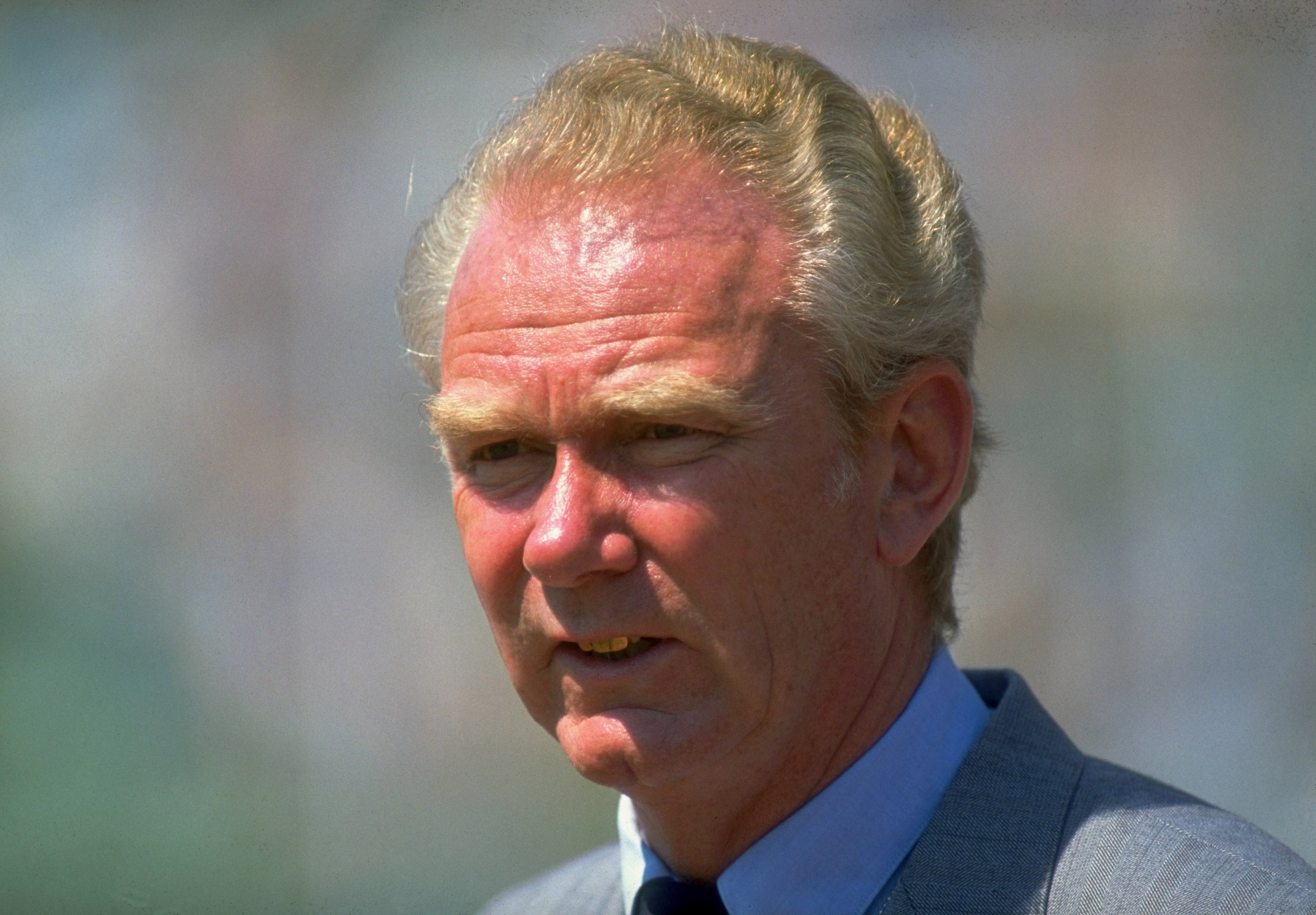

Lobanovskyi Avenue is named in honour of one of the greats of Ukrainian history – a man who stood for everything that Russia is now seeking to destroy. That man was Valeriy Lobanovskyi, and he was the father of Ukrainian football.

Was it coincidence that this was where that shell was aimed? Or was it a deliberate attempt to strike at the memory of so revered a figure, responsible for putting Ukraine on the world map as no one else has?

Back in the 1980s, as a coach who was globally admired for his vision and sophistication, Lobanovskyi presided over some remarkable football – the best in Ukrainian history, as good as any football of its era.

For all that Ukraine was, at the time, still part of the Soviet Union, Lobanovskyi’s achievements were identifiably Ukrainian, and I don’t think it’s too much to argue that, in its own way, the story of Lobanovskyi and of the formidable teams he shaped informs what is happening in his country right now.

I discovered Lobanovskyi slightly by chance. In the spring of 1986 I happened to be on holiday not too far from Lyon when the French city hosted the final of the European Cup Winners’ Cup – Atletico Madrid v Dynamo Kyiv.

It was too good an opportunity to miss. I knew almost nothing about Dynamo Kyiv, but what I witnessed changed all that. Kyiv – managed by Lobanovskyi – won the match 3-0, and they played such dazzling football that I was completely smitten.

A remarkable turn of events followed the Kyiv team’s triumph, and in what it said about the relationship between Russia and Ukraine it resonates to the present day.

Lobanovsky was a rebuke to the greater forces of the Soviet Union/Russia. He represented an independence of spirit that looks very much like part of what has driven Putin over the edge

Within a few weeks of Dynamo Kyiv returning home with the European Cup Winners’ Cup, the World Cup was due to get under way in Mexico.

The Soviet Union had qualified for the tournament but were not in great shape. Expectations were low. Did Lobanovskyi provide an opportunity for drastic action?

He’d managed the national team for two brief spells previously. But he’d never been asked to take it over with a World Cup looming. That, however, is exactly what happened in 1986. The policy would be very simple – club would become country.

The Soviet Union’s opening match of the World Cup was against Hungary. The team that took the field that afternoon contained no fewer than 10 Dynamo Kyiv players. No country has ever been represented by so many players from the same club. The result: Soviet Union 6 – Hungary 0. Or, in effect, Ukraine 6 – Hungary 0. Or indeed, Dynamo Kyiv 6 – Hungary 0.

The football world looked up. In the manner of Soviet teams across all sports, this one was supremely well drilled but it also had flair. The players could express themselves. The team attacked with speed and incisiveness, and soon the question was being asked – could the Soviet Union under Lobanovskyi actually win the World Cup?

The team, however, had fatal flaws. They only really knew how to attack. In the second round they came up against a Belgium team who were destined to reach the semi-finals. It was a pulsating match, with the Soviet Union playing brilliantly when going forward. But their defending was awful and they ended up losing 4-3 after extra time.

In spite of that disappointment, the club/country experiment was deemed to have been a success. Dynamo Kyiv and the Soviet Union: they became one and the same, both teams coached by Lobanovskyi, and things remained that way for the rest of the decade, right up to the fall of communism.

I was so captivated by the football they played that I found ways to see them whenever I could. After Lyon, I followed Kyiv/the Soviet Union to matches in London, Glasgow, Swansea, Paris, Berlin, and Porto.

It was in Porto in 1987, when Dynamo Kyiv were playing the Portuguese team in a European Cup tie, that I sat down in a hotel lobby and, through an interpreter, interviewed Lobanovskyi.

The interview was about football not politics. Lobanovskyi was serious-minded, his presence forbidding. He expounded on his philosophy of “collective speed”, whereby with every pass he sought his players to eliminate at least one member of the opposition.

It was the morning after the match, and as Lobanovskyi and I spoke, a few of the Kyiv players, having been given some time to themselves, filed into the hotel carrying designer bags from a shopping trip. There was something poignant about the opportunity they’d taken to gather up Western luxuries which one imagined were not available to them back home.

The high point of this period of Lobanovskyi was the 1988 European Championship when his Kyiv-dominated Soviet Union reached the final, only to lose to The Netherlands – a match best remembered for a wonder goal by the Dutch striker Marco Van Basten.

Lobanovskyi produced one more great team – the Dynamo Kyiv team of the late 1990s which in the young Andrei Shevchenko contained a player destined to be the greatest striker in the history of Ukrainian football.

By now the Soviet Union had broken up, Ukraine was Ukraine, and Lobanovskyi was a national hero. When he died, in 2002 aged only 63, the Ukrainian parliament held a minute’s silence in his honour. The Dynamo Kyiv stadium became the Valeriy Lobanovskyi Dynamo stadium, and then there was Lobanovskyi Avenue, now scarred by Russian aggression.

Lobanovskyi was a rebuke to the greater forces of the Soviet Union/Russia. He represented an independence of spirit that looks very much like part of what has driven Putin over the edge. It must be galling for Putin to remember how the Soviet Union football team was once made up entirely of Ukrainians.

Maybe Russia knows that if it is ever going to have a world-beating football team it’s going to need some Ukrainians in it. Lobanovskyi’s legacy lives on. In that sense there is something powerfully symbolic about Ukrainian football – and for Ukrainian football, read Valeriy Lobanovskyi.

Russia can bomb Lobanovskyi Avenue all it likes but I doubt it could ever destroy the memory of the man it’s named after.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments