‘This is what madness looks like’: Inside Putin’s endgame for Ukraine

As Russia claims to have seized the eastern town of Soledar after months of fighting, Bel Trew reports on what it means for Moscow’s invasion – and for the Ukrainians in the path of any further advance

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The only way for many to survive the “meat grinder” of Russia’s 11-month invasion of Ukraine is to live a half-life underground.

In the besieged eastern city of Bakhmut, deep in the burrows of a Soviet-era apartment block, Ludmilla, 47 and Tamara, 65 are busy trying to create some sense of normalcy in the musty four walls of the communal cellar. The sound of shelling is dulled inside the building, the ceiling gently pulsing with the booms – but the fear of a hit is a constant.

Residents of the block have built a functioning stove to cook and keep warm. “If needs be, we don’t need to surface,” says Ludmilla, wearing two coats, as she shows us the oven in the gloom. “We’ll stay here all winter until it’s over.”

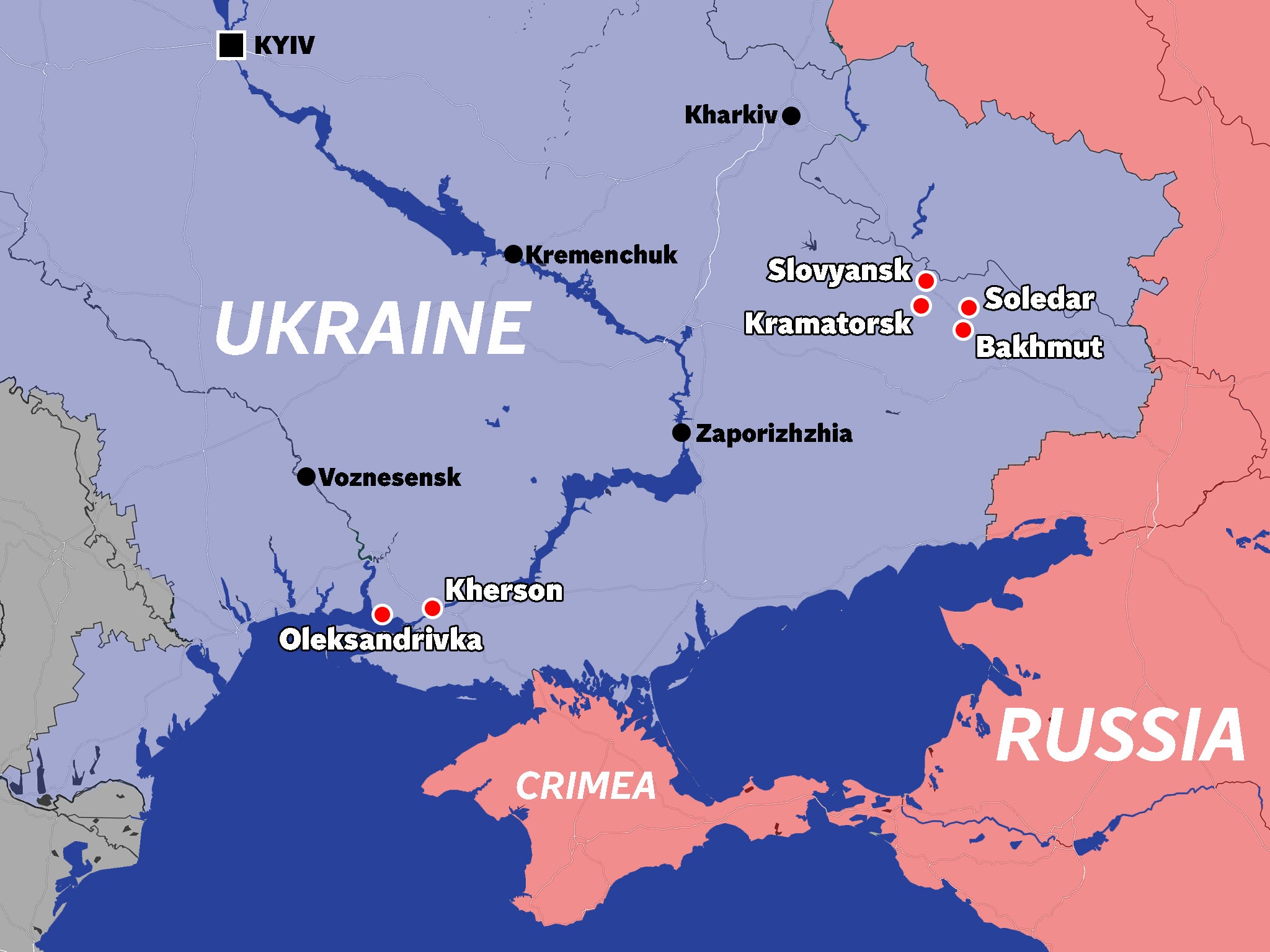

Bakhmut and the area that surrounds it, including the neighbouring salt-mining town of Soledar, has become the epicentre of some of the more ferocious and bloodiest fighting between Russian and Ukrainian forces. This is because the area is a gateway for Moscow’s troops to push further into Ukraine – with president Vladimir Putin having set his heart on taking the whole of what is known as the Donbas, encompassing the eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk.

Russia’s defence ministry announced on Friday it had seized Soledar, although Kyiv disputes this and says the fighting goes on. If Moscow takes both Bakmut and Soledar, they will control key supply lines and have a platform to advance on two bigger cities – Kramatorsk and Sloviansk.

That, in turn, could lead to other towns and cities across the Donbas to fall like dominos – and give Russia control of Ukraine’s industrial heartland, something Moscow has coveted since 2014, when it illegally annexed Crimea.

Taking this territory, along with securing the land corridor to Crimea through the southern region of Kherson, would also give Putin the one thing he has been looking for: a battlefield victory potentially big enough to extricate his embattled forces from this bloody war.

Ludmilla and Tamara are among the youngest left in Bakhmut, which had a pre-war population of some 70,000 people and was once better known for its sparkling wine.

“My daughter left with her family, all the young generation evacuated,” Ludmilla says. “It’s only the people who can’t move that stay. Rent is too expensive.”

Tamara has only remained in Bakhmut because of her octogenarian parents.

“My father says he lived through WWII and won’t leave and so we’re here,” she says flatly. “He says this is our home why should we go?”

But there may be little left of Bakhmut to call home. The city is only just “holding on” according to Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky.

While Bakhmut’s few remaining inhabitants hardly dare to go above ground, the pock-marked road from there to Soledar is populated only by ambulances and humanitarian vehicles.

Tens of thousands of Ukrainian soldiers have been sent to the frontlines in Soledar and Bahkmut to face the full ferocity of the army of the Russian Federation, its proxy soldiers and mercenaries like the Wagner group. And in recent days it appears that the Kremlin’s tactic of throwing bodies at the problem has worked.

Zelensky had previously acknowledged that the situation in Soledar is “difficult”, but maintained that Ukrainian defenders had bought more time by holding on, and that Kyiv will eventually drive Russians out of the entire eastern region.

“Everything is completely destroyed, there is almost no life left,” the president said during one of his daily addresses. “And thousands of their people were lost: the whole land near Soledar is covered with the corpses of the occupiers and scars from the strikes,” he said. “This is what madness looks like.”

In the rage of war, civilians are going missing including two British citizens, Christopher Parry, 28, a running coach and Andrew Bagshaw, 48, a resident of New Zealand. They were last seen heading to a northeastern corner of Soledar to evacuate the elderly on Friday.

Their desperate families have spoken about feeling “raw” following their vanishing. The head of Wagner Yevgeny Prigozhin claimed late Wednesday that his forces have discovered a body and published photos of the pair’s passports.

Their friends who live with them in the nearby city of Kramatorsk and joined them on evacuation missions fear that in the frenzy, the frontlines caught up with them.

“Everything is moving so fast,” says one flatmate who declined to be named.

“We are scared they might not have known where the Russian positions were.”

The fighting in the east has consumed both sides in recent weeks, given the strategic importance – but Russia has not forgotten Crimea in the south.

The southern front

What was once the only evacuation route out of the region of Kherson is full of the scorched wreckage of cars. This is Oleksandrivka, west of Kherson city. Tripwires frill the single-lane road that runs along a short landbridge rising like a spine out of the heavily mined marshlands around the seaside town.

Every metre or so, a destroyed car marks the failed attempt of a civilian trying to escape the eight-month Russian occupation. Kherson region – with its main eponymous city of 280,000 people – was one of the most significant and fastest victories Russian forces enjoyed. Up until November, it was also the last regional capital that Moscow had captured and still held.

But with supply lines cut off and Ukrainians pressing an advance in November, Putin’s generals ordered a withdrawal to the east bank of the River Dnipro that cuts the region in half. This was to protect the land corridor to the nearby Crimean peninsula that Russia had successfully formed from towns like Melitopol. Crimea is home to Putin’s Black Sea fleet and a hallowed prize for the Kremlin since it was annexed in 2014.

Oleksandrivka town had only been liberated two days before The Independent got there, after an eight-month occupation, but the soldiers had been quick to shift the bodies that we watched being transported to nearby Mykolaiv in large refrigerated trucks.

In the disarming quiet, de-miners get to work, marking each half-metre of movement forward with red spray paint.

“All these vehicles are signals of potential war crimes,” says Dmytro Sheshenko, the chief prosecutor of the district whose teams are preparing to investigate. Behind him de-miners shout at us to be careful as we fail to spot a tripwire that, gossamer-like, swings gently in the breeze. Then, a solitary car appears.

“My child is 10 years old, and he already has grey hair,” says Dima (not his real name), 43, sitting behind the wheel. He is a veteran soldier and father-of-three who is visiting his hometown Oleksandrivka for the first time since the invasion.

He was already deployed to the front when the war broke out and was powerless to do anything when the Russians swept through his neighbourhood on 14 March.

“My family barely got out. People were shot. Many people died both military and civilians,” he adds with despair.

“The Russians were so fast, we couldn’t do anything.”

He says his house was one of the first to be destroyed.

“I don’t feel anything. I am numb. Everything is gone. The only thing I have left is my car.”

Back in Kherson, Russian forces are deeply entrenched along one side of the Dnipro river, just a few hundred metres across the water from the city centre. They are heavily shelling Ukrainian positions.

“The enemy has taken up their positions and in the future, will use much more means of destruction. As Russians always do, they will shell,” says Kurt, a Ukrainian commander whose unit was among those that liberated Kherson and the surrounding areas. We cannot name the unit for security reasons.

He is so concerned about the ferocity of future attacks, he wants civilians to evacuate.

“The children and women especially should leave. Their snipers have already taken up positions, at night we have small arms fire.”

Kurt believes that rather than trying to cross the river again the Russians will aim to bed down even more deeply on the left bank of the Dnipro.

Other soldiers in Kherson The Independent spoke to admitted that while relinquishing Kherson city was an embarrassment for Putin, it was not a significant strategic loss because he “does not need it”. Trying to hold Kherson city would only have bled their forces dry when the real prize is the east.

The children and women especially should leave. [Russian] snipers have already taken up positions

And so for the civilians who insist on staying and living in Kherson, they know even if the more kinetic battlefields are further away, it is only going to get bloodier here.

“They want to make our lives a daily misery,” says Tetiana, 44, who with her husband Boris is queuing up for food aid outside Kherson city railway station.

“How hard is it to keep shelling us from across the river?”

The Eastern Front

Back in Bakhmut and Soledar, soldiers, the Ukrainian army and pro-government social media accounts have begun releasing a steady stream of defiant mobile phone videos of heavily wounded Ukrainian soldiers. In the clips, they insist that while the battles are bloody and awful, they are standing strong.

“I am actor Dmytro Linartovych, a soldier of air assault troops in Soledar,” says one young man whose mangled face is so swaddled in gauze he can barely speak. The video is posted to the army’s official Twitter account.

“Remember that we are on God-given land. We will never be broken. We are winning,” he adds weakly.

But this defiance does not reflect the reality on the ground.

With Soledar fallen, nearby Bakhmut could be next and then potentially the rest of the Donbas region – giving Putin that face-saving, albeit pyrrhic – “victory” that he so craves.

In the city, elderly residents keep their spirits up as much as they can do – emerging above ground in the rare breaks between shelling.

“We are hoping there will be electricity, water, and some good news,” says Tamara as the deafening crash of incoming punctuates her sentence.

“We are hoping everything will be okay. Hoping.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments