In the dark shadow of Putin’s war: Murder, mass graves and torture mark a Russian retreat

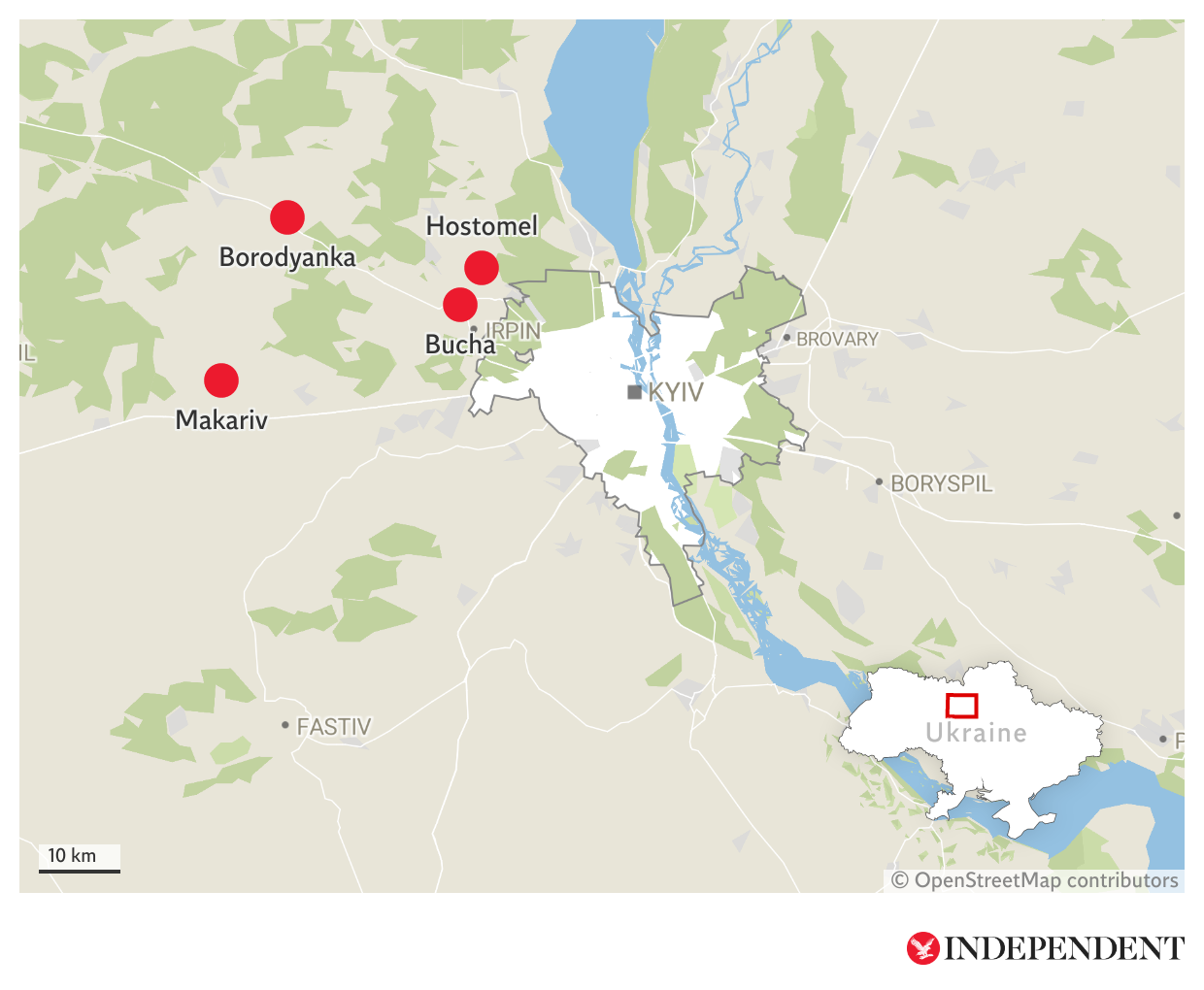

Special Report: A man watches a Russian missile destroy his family’s home in front of his eyes. A teenager avoids a summary execution by seconds. In Borodyanka, Bucha, Hostomel and Makariv, Bel Trew finds a Russian retreat marked by a trail of murdered civilians, mass graves and devastation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It took the firefighters more than a month to reach the bombed-out building and begin to pull the bodies out. Anyone who had survived the Russian attack on the block of flats in Borodyanka would have long since suffocated or died of thirst in this lonely concrete tomb.

Vadym, whose family is under the rubble, knows this. But he cannot let go of hope. Islanded by grief, the 45-year-old waits in front of the skeletal remains of the tower block for news of his loved ones’ bodies. The fisherman, who by chance was outside when the missile struck, clutches his winter jacket like a lifebuoy. It’s the only possession he has left in the world.

Just before 8am on that freezing March morning, he missed a call from his mother Lida, 64, while he was moving his wife and child to a bunker inside a nearby school.

A few metres in front of the block of flats, he tried to ring his mother back to urge her to relocate as well. Before the call could connect, he was thrown into the air. The world turned red and white and upside down. The sky exploded and imploded at the same time. When the dust settled, the centre of the nine-storey building had gone, gouged out by a ferocious fist of fire.

“It was so intense, I have never seen anything like it. It forced me across the ground,” he says in front of the block which yawns open to the sky. The second-floor flat where his mother, brother, sister-in law, and mother-in-law were living is now a pile of charred concrete.

“I don’t know if they made it to the basement but even if they did, there was no way to get to them. I tried so many times, but the bombing was so intense it was impossible. We couldn’t do anything but leave them there.”

Swathes of Borodyanka, 26 miles northwest of Kyiv, were wiped out by bombing and shelling in the ensuing days before Russian troops rolled in, occupying the area, looting and setting fire to shops, and shooting those Ukrainians who dared to venture out. Phone networks and power lines were cut, food and water became scarce.

And so the rescue operation was unable to take place until this Thursday, when Russian forces had pulled out. According to authorities, four bodies were pulled from the snarls of concrete and steel that afternoon, including a child, the corpses charred beyond recognition.

“Why target this? There was not a single Ukrainian soldier in the town when the war started. We were just families with children,” Vadym says.

“I am clinging on to hope but I also don’t believe in miracles. At least I want to locate the bodies so I can bury them properly,” he adds, breaking down into tears.

Borodyanka, Bucha, Irpin, Hostomel, Makariv: these are names now synonymous with some of Russia’s most brutal acts. Before they were chewed up in Russia’s Kyiv offence when President Putin launched his 24 February invasion of Ukraine, they were sleepy satellite towns unknown to the world.

A drip-feed of horror has emerged over the last few weeks from those who fled. Now, after Russian forces withdrew in their repositioning in the east, the true scale of these atrocities has been revealed. Hundreds if not thousands are thought to be dead. Ukraine’s prosecutor general, Iryna Venediktova, said on Friday 650 bodies had been found – 40 of them children – in the Kyiv region, though the search goes on for more.

Russia has repeatedly and vehemently denied targeting civilians and committing war crimes. The Kremlin said on Tuesday that western allegations of civilians executed in Bucha, particularly, were a “monstrous forgery” aimed at denigrating the Russian army.

But in more than a dozen interviews, residents of these towns dramatically contradicted these claims. They told of summary executions, torture and civilians shot as they tried to get supplies or flee. Some were reportedly raped.

The Independent has stumbled upon mass graves and execution sites, makeshift cemeteries and scenes of alleged torture. In Borodyanka, the gaping wounds of war scar almost every building in the centre; almost every shop has been looted. Empty shoe boxes scatter the main streets – locals say Russians had ransacked a footwear store, trying each pair on for size.

Groups including Human Rights Watch say they have documented multiple instances of possible war crimes. The laws of war prohibit the wilful killing, rape and torture, and inhumane treatment of both captured combatants and civilians in custody. Pillage and looting are also prohibited.

UN human rights chief Michelle Bachelet echoes these warnings. Her office says the horrors uncovered in these towns mark a new low in the war, with victims’ bodies desecrated in death.

The testimonies gathered by The Independent tell the true story of this bloody war, and shed light on Russia’s playbook for the entire country as Putin’s onslaught continues.

“We were left here alone, abandoned, without water, without food, without electricity, without light,” says Vadym’s sister Julia, 31, in tears as she too awaited news of her mother’s body.

“We had no warning, our world just collapsed around us.”

‘My life was going to end in this stupid way’

The soldiers forced 15-year-old Roman to his knees, pushed his face into the dirt, then fired two warning shots next to his head.

The bullets narrowly missed his father Viktor, 40, and a neighbour, who were laying face-down in the ground next to him. They had been lined up for an “execution” in their backyard in Bucha.

“Maybe we can waste the old ones and save the young one,” sneered one of the soldiers, pressing the barrel of his gun into Roman’s neck.

Moments earlier, Roman and his father had been fixing the roof of their partially destroyed building after hiding in a bunker through three days of intense bombing without food or water. A group of soldiers occupying the area had taken issue with this and ordered them to be summarily executed.

“I just remember being upset that my life was going to end in this stupid way,” the teenager says blankly. “But at the last second their commander came and ordered them not to kill us.”

Roman’s uncle was not so lucky, says his mother Tanya, 37, adding: “He was killed while trying to find supplies, but we don’t know why.”

Roman says they also stumbled upon a neighbour whose body had almost entirely been eaten by rats, and a woman who had been shot in her head, half of which was missing.

“We couldn’t work out who she was because there wasn’t enough of her face left,” he adds with a disarming calmness.

His street – Vokzalna – looks like it has been mauled. Every house, bar Roman’s, has been grabbed at by a giant claw.

In the centre lie the charred remains of a dozen beached Russian armoured vehicles: a column that early in the war had come under ferocious Ukrainian fire.

The Ukrainian authorities say at least 300 people have been killed in Bucha – around 50 of them through summary execution, though the death toll rises each day with the discovery of fresh corpses. The only word to describe Bucha and the surrounding towns is haunted.

There, wind whips through the rusty ribcages of shops, restaurants and supermarkets, a whisper of what the towns once were. Unexploded missiles and mines are wedged into roads. The walls of homes and fences are etched with “we have not left” and “children are inside” in a desperate bid to avoid being targeted by advancing troops. Still, the front yards have been bulldozed by tank tracks.

But the real horror is in the bodies – or bits of bodies – scattered everywhere. Dozens of civilians have been found with their hands tied behind their backs and shot. Other corpses are recognisable only because of the tell-tale flick of a charred spine, or a jaw, wedged inside upturned Russian tanks.

The last terrifying moments of families fleeing are frozen in chilling tableaux: in one Bucha neighbourhood, a crashed car is reversed up on to a banked pavement, the bonnet smashed by a shell, as a baby seat still attached to the seat belt hangs on the side.

In Hostomel, just north of Bucha, outside one home fragments of skull and brain fleck an airbag – in line with three neat bullet holes through the driver’s headrest. The body of the victim – shot dead as she drove her 11-year-old son – has been buried, a family who rescued the boy explain. He had been found screaming, pinned down beneath his mother’s lifeless body.

Then there are the graves.

Across Bucha, Hostomel, Makariv and Borodyanka, communal gardens of Soviet-era flats have become makeshift cemeteries as it was too dangerous to take bodies to morgues.

In Bucha we bump into Helena, 61, who shows us three she helped dig outside her flat window. Two contain men who lived in the building and were shot (one had his head smashed in with a blunt object first). The third, a man called Leonid, was killed by a grenade thrown into his flat “for fun”.

“It was the most horrific scene I’ve ever seen,” she adds in tears by his grave. “They knocked on his door [and] tossed in the grenade for amusement. He was missing a leg and half of his face. Only a few of us were brave enough to bury him.”

In a different neighbourhood, a few residents emerge from the shadow of a ghostly set of flats to show The Independent a hastily dug grave, for a man publicly shot in the central courtyard on 16 March because the Russians accused him of filming from his window.

“We were too afraid to bury the body at first because they shot at anyone who walked outside. But then the dogs started to eat him so we asked if we could at least cover him with soil,” says Anya, 70.

This is just one of three summary executions that occurred in this block alone, they say. In another, a 14-year-old boy apparently escaped because he played dead next to his father’s corpse.

Alexei, 43, who lived two floors above, takes us around the building, showing where Russian forces crowbarred open and ransacked every single apartment. TVs computers, clothes, even towels are gone.

The pavement in front of the building is covered in coins. “They looted the entire block of flats, down to the kids’ piggy banks. They were breaking them open here,” Alexei says with a shrug.

He adds that residents had to shield themselves by blocking windows with washing machines and heaters.

“We needed to protect ourselves from the sniper who would take potshots at people from that window.”

‘We stopped counting bodies at 100’

On the road from Borodyanka to Makariv, the partially burnt corpse is almost too camouflaged to spot amid the shadows of the wood.

Dressed in jeans and a checked shirt, the body’s hands and legs are tied. He is too small to be an adult. The Ukrainian soldiers who found him three days ago while de-mining the area estimate he is no older than 16.

Just five metres behind him is the first Russian trench. Ten metres beyond that is a Russian camp clearly abandoned in a hurry. A cafetiere has been left with the last dregs of coffee still in the bottom. Socks and underwear are drying on a tree. In the middle is a chicken coop, with two chickens pecking through two bags of grain split open. There is a half-open sewing kit, and dozens of buttons. A makeshift kitchen has been left with all the supplies intact.

“We found a further three more bodies of Ukrainian soldiers whose hands were also tied behind their backs a few hundred metres way ” a soldier, who declines to give his name for security reasons, adds.

“We are still trying to identify this teenager and find out what happened.”

This teenager is apparently one of dozens of civilians shot by Russian military in Makariv, according to local officials. The Independent could not verify true death tolls but has collected testimonies across the Kyiv region and has seen bodies indicating the practice was prevalent.

In Demydiv, 5km north of Kyiv, which was occupied on the first day of the invasion by Russian forces, Denis, 27, who volunteered to distribute food and medicines in the town, tells The Independent he was shot, beaten, stripped and tortured in a basement by Russian forces.

A month into the war, Russian troops accused him and one of his friends, also a volunteer, of secretly revealing Russian positions to Ukrainian forces after a strike killed three Russian soldiers in a house they were using.

The soldiers shot them, beat them, stripped them and then forced them into the boot of two vehicles, Denis says. The pair were then taken separately to different basements where, bleeding and wounded, they were beaten until their release.

“They threatened to behead us and kept saying ‘our soldiers died because of you’,” the young man continues. “They were drunk and beating us continuously. My friend’s foot looks like mince.”

In a hospital in Kyiv, Tanya, 50, from Moshun, another satellite town in the Kyiv region, says trigger-happy soldiers shot her husband in the hand, shoulder and leg because he had tried to venture outside to put out a nearby fire started by shelling.

She had to make a tourniquet out of bedsheets to keep him from bleeding out as they waited for rescue.

And so now, parts of her husband’s leg were being amputated as she spoke to The Independent. “We were also shot when we tried unsuccessfully two times to flee to safety – they were shooting at anyone trying to escape,” she adds. In Bucha, meanwhile, Father Andrei, of St Andrew and Pyervozvannoho All Saints church, says most of the bodies he received had been shot, with their hands tied behind their back. Some also had signs of torture and were blindfolded.

The pastor had been forced to dig two huge trenches behind the glittering domes of his church when it became too dangerous to venture to the nearby graveyard and the morgues were overflowing.

“At first we had the body bags from the morgue but they quickly ran out so all we could do is place the bodies in this hole,” he says, gesturing to the pit.

“We don’t know how many [are] buried here. We stopped counting at 100.”

Identifying the bodies is a nightmare, he says, now that they have been exhumed and sent to Kyiv. Locals improvised. One woman – shot as she tried to flee Bucha in her car – was buried with her car number plate to help identify her later.

‘It was personal’

Back in Borodyanka, all Vadym and his sister Yulia can do is stand and wait. Friends who also knew families huddle in tears. Firefighters work hard to peel open the layers of concrete to find bodies. An army of volunteers, meanwhile, work to clear the abandoned streets.

“I have no other explanation than it was done on purpose,” says Vadym, gathering his words through several pauses.

“This is clearly a residential area, it has no strategic value other than to terrorise the inhabitants.”

Together with his sister they piece together the timeline of attack, and realise the fighting worsened after a column of Russian forces was destroyed.

“The only way we can see this is that it was a deliberate attack on civilians, that it was personal.

“This was hatred. This was revenge.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments