How ‘street justice’ and retribution complicate the war in Ukraine

Collaborators with Russian forces are being brought to justice – but not always through official means, as Kim Sengupta explains from Kramatorsk

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As he rescued civilians from Kupyansk – an area retaken by Ukrainian forces but still under heavy Russian fire – Dmitry Lozhenko was approached by a group desperate to be evacuated.

What made them different from other residents seeking help was that they offered a lot of money to be taken out, and were keen to avoid the vetting carried out by Ukrainian authorities on anyone leaving formerly occupied territories.

“I was very suspicious that these were collaborators,” said Dmitry, a volunteer for the group “I am Saved” which has saved thousands of residents from dangerous situations. “They probably couldn’t get to Russia and were trying to get away before they were caught. Of course, I did not take them and passed on the information to the appropriate people.”

As Ukrainian forces continue their swift and successful offensive through the northeast and south of the country, some of those who had sided with the invading Russians have been left stranded and are now deeply worried about retribution.

Some have disappeared, such as Kupyansk’s mayor Hennaidy Matsegore, who handed over the key to the city to Moscow’s forces and urged citizens not to resist. He was charged with treason by Ukraine but is now likely to be across the border.

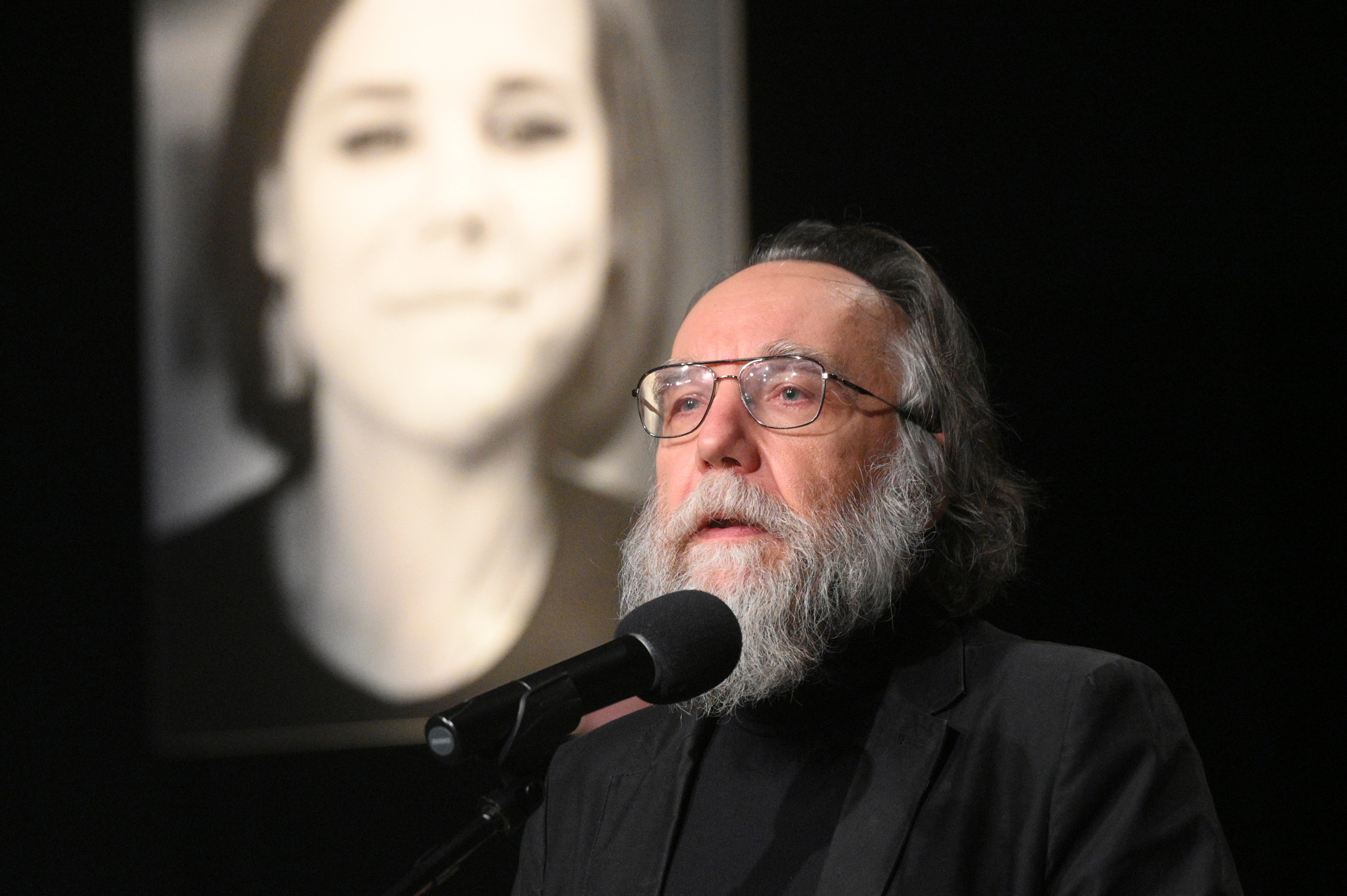

However, being inside Russia does not guarantee safety. It is increasingly believed that Ukraine sanctioned the assassination of Darya Dugina, a Kremlin-supporting journalist and the daughter of Alexander Dugin, a Russian nationalist ideologue. Ms Dugina was killed near Moscow in August by a bomb planted in a Toyota Land Cruiser belonging to her father, who may have been the real target. The conclusion by United States officials that a hidden Ukrainian hand was behind the attack, as reported by The New York Times, had been the generally held view in diplomatic and security circles.

The US Treasury had sanctioned Ms Dugina four months before her killing because of her part in a disinformation operation carried out by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a long-term Putin ally and the founder of the Wagner Group whose mercenaries are fighting in Ukraine.

Mykhailo Podolyak, an adviser to President Volodymyr Zelensky, denied Ukraine’s government was involved in any way. “Before Dugina’s murder, the people of Ukraine and representatives of the Ukrainian authorities did not know about her public activities and her influence on propaganda programmes,” he said. He did not mention Kyiv’s view of her father’s activities.

While Ms Dugina is believed to be the first to be attacked abroad, almost 35 Ukrainian officials who had collaborated with Russia or had been appointed to official posts by Moscow have been assassinated and injured in operations inside occupied territories.

Those deemed guilty of treachery have been shot, stabbed, blown up, poisoned and hanged, illustrating the ruthless and lethal determination of those hunting them down – Ukrainian intelligence officials working with partisans, according to various accounts. In June, Dmytro Savluchenko, an official of the Nova Rus youth organisation in Kherson, died after his car was blown up. The force of the explosion burned out two other cars and damaged a four-storey building.

There were nine assassinations or attempts in August alone. Targets included Volodymyr Saldo, head of the occupation administration in Kherson, allegedly poisoned by his personal chef but survived; Vitaliy Gura, the deputy mayor of Nova Kakhova, reportedly shot dead; Aleksandr Kolesnikov, the deputy head of traffic police in Berdyansk, killed in a blast; Ivan Sushko, the mayor Mykhaylivka, in the Zaporizhzhya region, killed by a car bomb.

In September Artem Bardin, the military commander of Berdyansk, died after his booby-trapped car exploded in an administrative building, severing his legs. This week Olena Shapurova, the education chief in Melitopol, was injured in a car bombing.

Collaborators are also being pursued through the justice system. Ukraine has opened inquiries into 1,309 suspects and launched 450 prosecutions. Those under investigation include judges, police chiefs and mayors. Questions are being raised, however, of what exactly constitutes sedition and how acts of coercion, cooperation and willing collaboration are differentiated.

It has been claimed, by Ukrainian officials, that many of these attacks ascribed to Ukrainians were really the result of rivalry between Russian and separatist pro-Russian security officials. Violent score-settling has been a feature in the politics of the Donetsk and Luhansk “People’s Republics” and there are examples of rival factions within the Kremlin security apparatus undermining each other.

Oleksiy Danilov, secretary of Ukraine’s National Security and Defence Council, has claimed that Russian intelligence was responsible for Ms Dugina’s death. He also claimed, in the early days of the war, that attempts to assassinate President Zelensky by Chechen special forces were foiled, with some of them killed, due to information received from Russian intelligence (FSB).

He said at the time: “We are well aware of the special operation that was to take place directly by the Kadyrovites [special forces of Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov] to eliminate our president. And I can say that we have received information from the FSB, who … do not want to take part in this bloody war. And thanks to this, the Kadyrov elite group was destroyed, which came here to eliminate our president.”

Mr Danilov might have been attempting to sow division between Russia and its ally. However, it has been pointed out that Kadyrov, who has been critical of the performance of the Russian military in the war, volunteered that some of his men had been killed in operations around Kyiv when it was not publicly known that they had been there.

Security officials from Britain, the US and eastern Europe told The Independent they do not have evidence that attacks on collaborators have been due to internecine strife in Russian or separatist ranks.

British and American officials stress their concern that any Ukrainian involvement in the death of Ms Dugina could lead to retaliation by the Kremlin, with escalating and severe consequences.

“One can’t be too surprised at the Ukrainians meting out unofficial justice to those they consider traitors,” said a Western security official. “The Russians, as we know, have themselves carried out assassinations of enemies outside their country. But the killing of Darya Dugina could have repercussions which could rapidly get out of control. That, we think, is what the Americans have been impressing on our Ukrainian friends.”

Some who have suffered at the hands of the Russians and their supporters within Ukraine welcome the retribution.

Sergei Pymonenko was arrested and severely beaten in Kupyansk by Russian and separatist interrogators.

“I do not have any problems with punishment being given to traitors,” he said. “I understand if they had to be dealt with by our people, given street justice before they fled to Russia.

“Others who are caught should be put on trial and jailed for a very long time if they are found guilty, although I think some of them may be freed in prisoner exchanges.”

Mr Pymonenko was hesitant about giving his views on the killing of Ms Dugina. “Look, I don’t know the facts on this. I don’t have information, so I do not know if this was necessary or our government was involved... but don’t forget, we are in a war.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments