‘Turkey got what it wanted’: An Erdogan victory, a poll bump, but little substance in Nato expansion deal

Though hailed as a great victory by Turkey, analysts say only minor concessions were given by Finland and Sweden

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was criticised by his political opponents as too little, shrugged off as unenforceable by experts and ultimately may do little to improve his political fortunes ahead of major elections scheduled for a year from now.

But Turkey’s agreement to allow Sweden and Finland join Nato in exchange for concessions generated positive press and accolades among supporters of the government and sympathetic media, a rare island of good news for President Recep Tayyip Erdogan amid a sea of economic troubles.

“Turkey got what it wanted,” declared the staunchly pro-government A Haber TV.

The memorandum of understanding signed on Tuesday will probably cool hostility towards Turkey in Washington and other capitals at a time when the western powers are struggling to present unity in the face of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

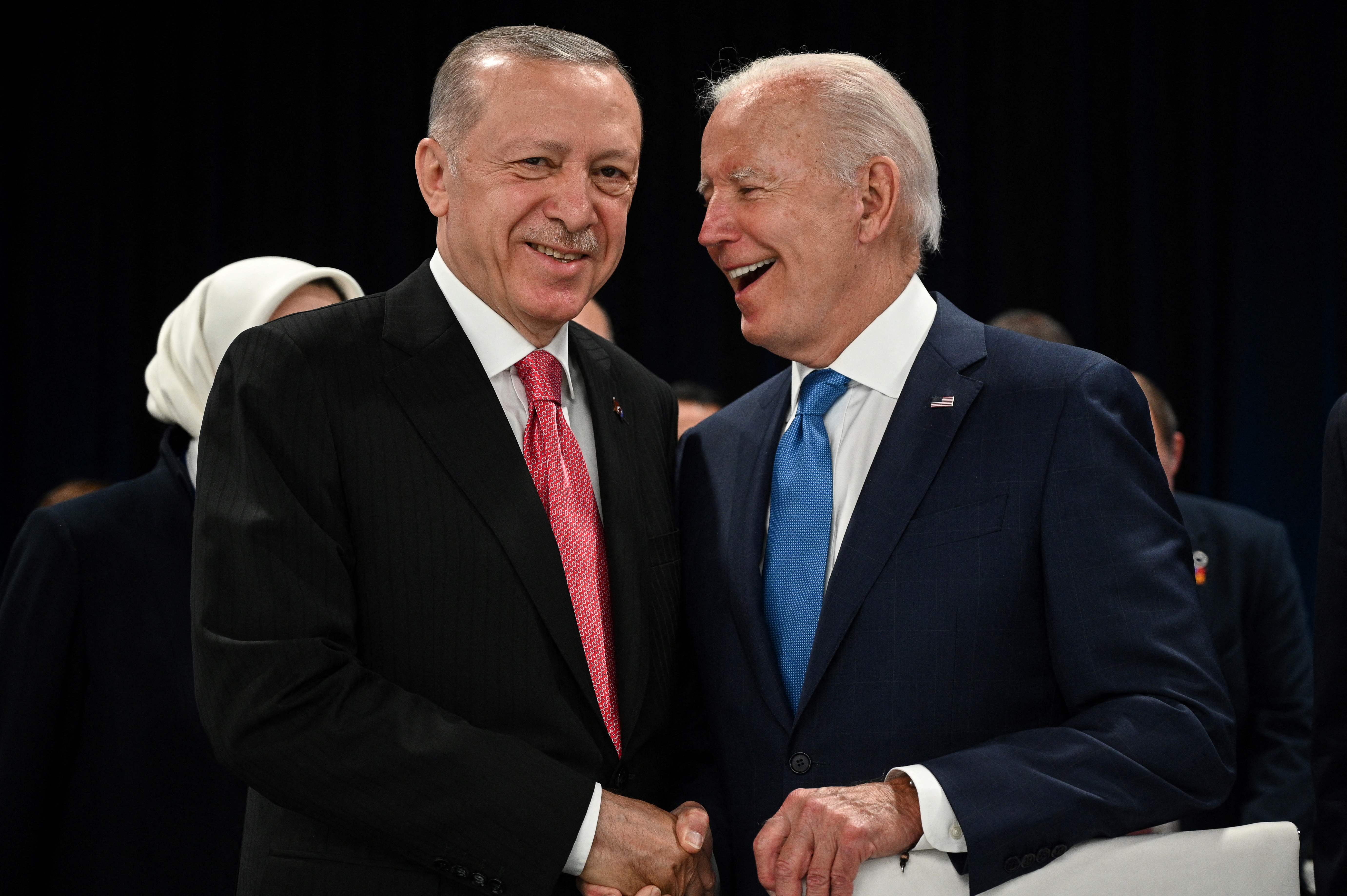

President Joe Biden and other Nato leaders had urged Turkey, Sweden and Finland to put the matter to rest before the summit got underway. Turkey was feeling the pressure, as was Sweden, whose historic sympathy for ethnic Kurds was viewed as the primary stumbling block to allowing it and Finland into the alliance.

“It was a diplomatic breakthrough,” said Minna Alander, a northern Europe specialist at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs in Berlin. “Erdogan needed a win and he got something that he could present as such.”

The Turkish leader had been threatening to scuttle plans to allow Sweden and Finland to join Nato, arguing the two countries were not doing enough to fight what he described as terrorism. His government had demanded the two countries hand over terrorism suspects and admit past wrongs.

Mr Erdogan also demanded that Finland and Sweden lift an arms embargo imposed against Turkey in 2019 and distance themselves from Kurdish nationalist groups that have a presence in Scandinavia before they are allowed to join the alliance.

They agreed. But Stockholm and Finland would have likely had to drop the arms embargo if they had joined Nato anyway.

“In future, defence exports from Finland and Sweden will be conducted in line with Alliance solidarity,” said the memorandum.

Mr Erdogan had also wanted a long-coveted tete-a-tete with US President Joe Biden, which he got on the sidelines of the Nato Summit in Madrid, and appeared to further secure a deal to procure American F-16 fighter jets.

But the US was already on track to sell the warplanes. Both the Pentagon and White House had urged a deal to go ahead following Ankara’s removal from the Nato programme to deploy next-generation F-35 warplanes over Turkey’s purchase of Russian anti-aircraft batteries. The Russian weapons violated US sanctions.

The agreement, which contains no enforcement provisions, offers no guarantees on whether the Scandinavian countries would do anything additional to what they say they have been already doing to curtail activities of Kurdish-led militant organisations and those of an outlawed Islamist religious cult led by exiled cleric Fethullah Gulen, who is accused of being behind a 2016 coup attempt in Turkey.

Still, the memorandum contained some language that appeared to offer concessions to Turkey, including commitments to not only combat the activities of the already outlawed Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) but also those of its Syrian branches, which are part of the coalition of forces battling Isis.

Turkish media hailed the agreement as securing the “full cooperation” of the Scandinavian countries against Kurdish groups, and boasted that the memorandum referred to “FETO”, a controversial term used by government supporters to describe Gulen’s movement.

It contained a commitment to elevate the review of judicial cases against individuals Turkey is seeking to extradite, though without any explicit commitment to hasten or follow through on any extraditions.

“Ultimately Turkey got what it could get under these circumstances,” said Sinan Ulger, a Turkey specialist at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “It’s a good deal, in that every party can go home and claim they got what they wanted.”

The deal also may put to rest accusations that Turkey was doing Moscow’s bidding by sowing discord within Nato at a time when Russia is waging war against Ukraine and President Vladimir Putin and his enforcers are issuing daily threats against the rest of Europe.

“I don’t think there was any attempt to please Russia,” said Toni Alaranta, a specialist on Turkey at the Finnish institute For International Affairs in Helsinki. “Turkey has been trying to do this balancing act between Russia and the west for some time but it does not mean Putin and Erdogan had some kind of deal. The relationship between Russia and Turkey is just as complex and ambiguous as it is between Turkey and the west.”

Sweden and Finland have been working closely with Nato in joint military exercises and in security arenas such as intelligence for decades. That coordination has intensified after the 2014 Russian attack on eastern Ukraine, and has become even more pronounced since Moscow’s ongoing war against Ukraine. The two Nordic countries have long been integrating their defence strategies and operations with Nato, regardless of formal membership.

“They have both been able to work as the closest possible way short of membership since the 1990s,” said Ms Alander. “It was clear that Turkey can’t and won’t stop Finland and Sweden becoming members. Time was on Finland and Sweden’s side because the blocking strategy wouldn’t work after a while.”

The deal was criticised by some of Mr Erdogan’s opponents, who accused him of making a U-turn in the face of western pressure. Opposition voices on social media decried his “retreat” and “inconsistency”, while several lawmakers accused Mr Erdogan of posturing for weeks before embracing a toothless deal.

Pollsters say that Mr Erdogan’s perceived tough stance on the Nato expansion issues and claims that he managed to get concessions have modestly strengthened his support, which has been lagging behind several major opposition figures in repeated surveys. But few believe it will make a difference come election time, which could take place next year.

“In the grand scheme of things these types of foreign policy successes are short-lived in a country that has a very turbulent news cycle,” said Mr Ulgen.

“The main issue domestically is not about foreign policy, it’s the economy. That matters much more than foreign policy actions. There might be a boost for Erdogan but it’s going to be limited and short-lived.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments