The families still searching for loved ones a year after Turkey’s earthquakes: ‘I don’t have a grave for my son’

The disaster in February 2023 killed more than 50,000 in Turkey and 6,000 in Syria. Lizzie Porter reports from two of the regions worst affected by the devastating tremors – and speaks to families struggling to rebuild their lives

Suna Ozturk has nothing but photos left of her daughter Tugba Kosar.

On a poster of missing people pinned up in her mother’s neat living room, Tugba’s smiling face beams out next to those of her sons, eight-month-old Mehmet Akif and three-year-old Mustafa Kemal. He liked diggers, and was named after Ataturk, the founder of modern Turkey.

“Tugba was a very forgiving person, and she was so happy to be a mother,” Suna said, as sleet falls across a steel grey sky outside in the central Anatolian town of Aksaray. “There are no memories left, just pictures.”

The 36-year-old and her children are among at least 145 people whom campaigners have identified as missing since the powerful earthquakes on 6 February 2023, which killed tens of thousands and devastated swathes of south Turkey and northern Syria. Activists say that the overall number of missing may be much higher than recorded figures, and includes Syrian refugees and other foreigners alongside Turks.

The Independent has spoken with five families whose relatives disappeared after the earthquakes. They are battling bureaucracy, mental turmoil and, they say, government apathy to try to identify their loved ones.

“I spend a lot of time crying,” says Suna, 56. “I miss my daughter and grandchildren a lot. There is no purpose in my life any more.”

People were lost during the chaotic hours immediately after the earthquakes as survivors and victims were taken to distant hospitals and burial sites without their families’ knowledge, according to Nermin Yıldırım Kara, a Turkish MP who is campaigning for families of the missing.

“Those who searched in the rubble for family members could not keep track of which hospital their relatives were taken to,” she says. “In this situation, many citizens disappeared and could not be traced.”

Tugba had left her family and moved to Antakya five years previously, working as a teacher for disabled children. She married a local man, who survived the quake but is still too grief-stricken to tell his story.

The family lived in block A2 in a luxury apartment complex, the Renaissance Residence. Its collapse became symbolic of the construction failures linked to the earthquake and the enormous loss of life caused by current building standards.

“When the Residence building was completed, it was said it was from heaven,” says Yasin, Tugba’s brother. “There was a big opening and government people came to cut the ribbon. They told us it was safe.”

The building caught fire as it collapsed, and Yasin believes that his sister and nephews were caught up in the blaze before they were able to escape. Although the Residence site has now been completely cleared of rubble, their bodies have not been found. The Independent contacted Renaissance, but received no reply.

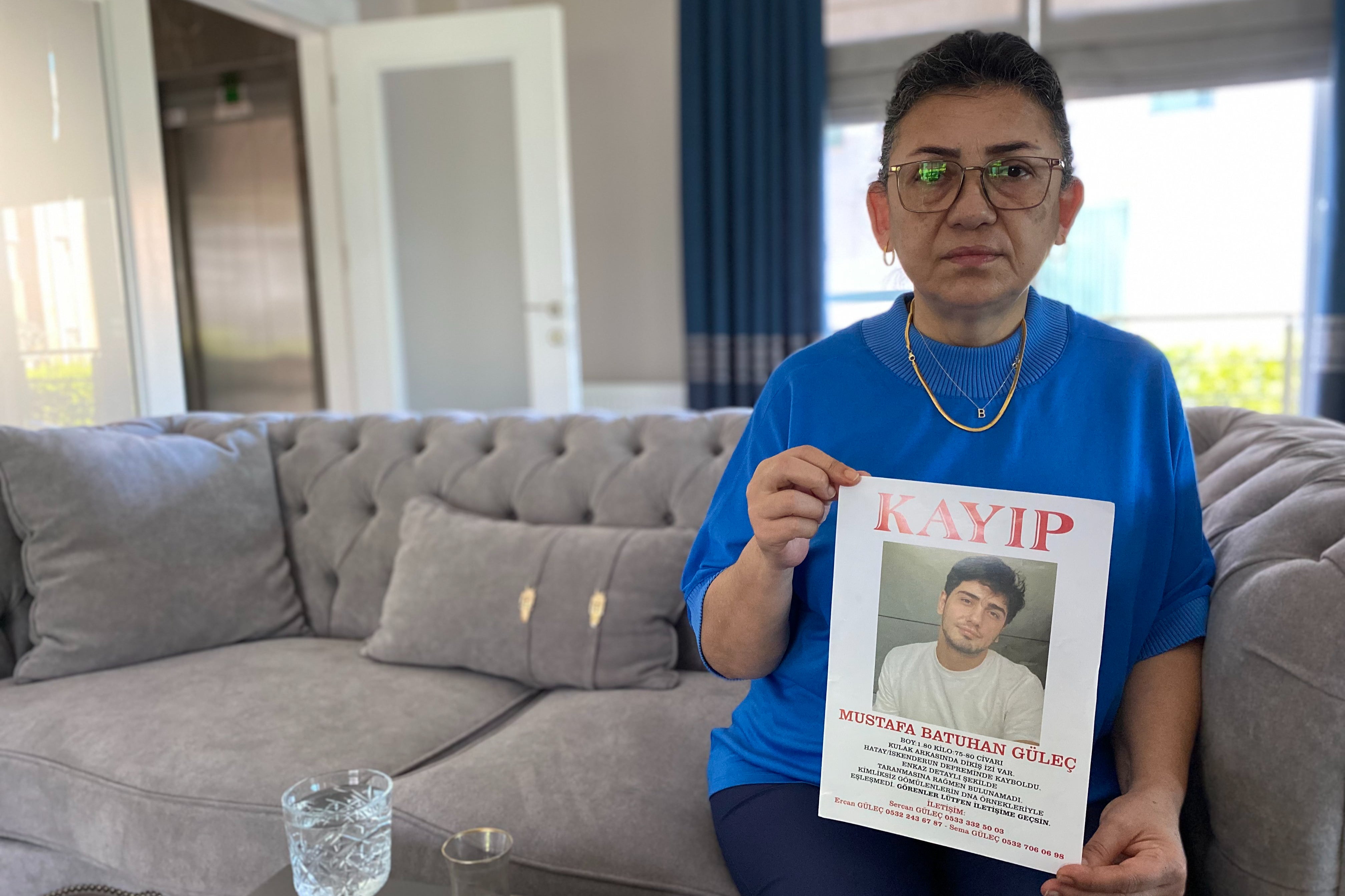

Sema and Ercan Gulec lost their son Batuhan, 25, when his block of flats collapsed on the outskirts of Iskenderun, a port town in Hatay province. The whole area was cleared of rubble without rescuers recovering his body. According to a witness who contacted the family after seeing Batuhan’s photo on social media, he emerged from the wreckage in a state of shock, but alive. He later got into a white civilian car and disappeared.

“I checked all the hospitals in Turkey where earthquake survivors were taken, but I could not find my son,” says Sema, 55. “I checked the graveyards and the pictures of the dead – but nothing. I went to the morgues. Nothing.”

Among the hardest things to cope with is the lack of clarity about what happened to Batuhan, who had just graduated from university with an architecture degree.

“All different types of scenarios come to my mind – maybe mafia or terrorists came for him. When you cannot find him, you think of all the possibilities,” Sema explains.

She now believes that her son died later on and his body was buried without DNA sampling. As such, unless his body is exhumed and tested, it is not possible to find a match with DNA that Sema and Ercan have since given.

The search for the missing has been complicated by the sheer scale of the disaster, which affected 17 provinces and caused tens of billions of dollars worth of damage. Amid the widespread fallout, families of the missing also feel forgotten by the authorities.

“We have not received the necessary support so far,” says Ayten Tuncer, whose sister Nesrin, 40, went missing after her house in Antakya city centre collapsed. “It is as if they see the losses as not having happened.”

An attempt to form a parliamentary commission to investigate the fate of the missing was voted down by MPs last month. That would have been an important step, families say, in increasing pressure on prosecutors’ offices across the disaster zone to accelerate the pace of both exhumations of bodies buried before they were identified, and gathering of DNA samples for possible matches with relatives.

“I have lost trust in the authorities,” says Sema. “I am angry. I am sad. Even if they cannot find my son, I want to feel that they have our backs. But they did not show that they do.”

Nermin Yıldırım Kara, who represents Hatay for Turkey’s largest opposition party, is also pushing for more work from prosecutors’ offices in the disaster zone.

“At this point, DNA matching and grave exhumations need to be increased,” she says. “The biggest demand of the families is that the authorities should make more efforts to ensure matching.”

The prosecutor’s office in Hatay province and the Turkish Ministry of Justice did not respond to requests for comment on how many missing persons had successfully been identified through DNA matches. A senior official from Hatay told Turkish media last week that DNA from 193 exhumed graves have not been matched with living individuals, and urged families to come forward to provide samples.

Among those who have found their missing relatives is Seyma Yılmaz. Her sister Hayriye Dilli, 43, was killed in the quake alongside her husband and their three children in the city of Kahramanmaras. Nearly three months later, on April 20 last year, Seyma received news that Hayriye had been exhumed from an unnamed grave and identified.

“When my sister's DNA matched, I both cried and laughed – at least we now know where she is,” she says. “Yes, we were happy for our dead. We were happy that we had found them.”

Seyma reburied Hayriye next to her husband and children.

Sema Gulec does not often return to the former site of her son’s home, which has now been cleared of rubble. But on the one-year anniversary of the quake this month, she will gather the courage to do so.

“I will go there this 6 February because I don’t have a grave to go to for my son, so I will go there instead. I will search for Batuhan until I find him.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments