'Russia, what do you want from me?’: The trial of a celebrated theatre director that's unlikely to end well

The controversial prosecution of director Kirill Serebrennikov – considered by many to be a test of creative freedom in Russia – does not look like it will buck the country's trend of guilty verdicts

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For two days last week, audiences at Moscow’s Gogol Centre theatre were served up an age-old question: “Just who in Russia has a happy life?”

In common with the rest of the theatre’s repertoire, Nikolai Nekrasov’s 1869 classic came with a bohemian workaround. The 2018 version had rap music, contemporary dance scenes, sex and fairly gratuitous nudity. But the gist of the tale remained the same: seven peasants traipsing across the largest country on earth, all in search of just one happy Russian.

The men move from priest to boyar, labourer to bureaucrat, men to women. Along the way, they are hindered by Russia: by incarceration, corruption, violence and vodka.

Eventually, they conclude no one is really happy or free. Only, perhaps, the tsar has it good. And even then, no one is sure.

The contemporary resonance of Nekrasov’s epic will have been lost on few in the audience. No one will have needed to see the cast’s “Freedom to the director!” T-shirts, revealed on final curtain, to know one important member of the production was missing. Or that the man, the virtuoso director Kirill Serebrennikov, was at home under house arrest, as he has been for the last sixteenth months.

Serebrennikov is one of four people who stand accused of forming a “crime syndicate”, defrauding the Russian state to the tune of 133m rubles (£1.5m). The charges relate to a grant awarded by then-president Dmitry Medvedev to develop experimental theatre.

Serebrennikov and his co-defendants deny all the charges, and have described them as “absurd”.

While the theatre world occasionally cuts corners with tax and cash payments, few believe the director’s problems are at all down to money. With provocative productions that touched on many taboo subjects such as homosexuality, Serebrennikov had, after all, created powerful enemies in the conservative elite.

For many, the trial has become no less than a test of creative freedom in Russia.

At the very least, it is a test of creativity in the state prosecutor’s office. Less than 0.1 per cent of all trials that reach court in Russia end with acquittals. So far, there is little evidence this case will buck the trend, with proceedings occasionally bordering on the absurd.

Initially, Serebrennikov and his co-accused stood accused of taking money for a play that supposedly never made it to the stage. Defence lawyers pointed out A Midsummer Night’s Dream was not only staged but actually received theatre awards.

This week, investigators presented several new tomes of “evidence” – invoices, all supposedly signed by Serebrennikov’s co-defendant, Alexei Malobrodsky. The vast majority of these documents bore no relation to the charges. Most were innocuous enough: phone bills, and electricity statements. But a substantial number of the documents also contained forged signatures.

Over the course of an hour, Malobrodsky and his lawyers attempted to raise objections with the presiding judge.

“This is not my signature, your honour,” Malobrodsky said. “These documents are forged and should not be considered.”

At one point, Malobrodsky’s lawyer, Kseniya Karpinskaya, called for the state prosecutor Oleg Lavrov to be removed from the case. Presenting false and tendentious evidence, she argued, showed he had no interest in the objectivity of his case.

Judge Irina Akkuratova promised to retire consider the request. Three minutes later, she returned with a decision that surprised no one.

“The judge does not see any basis for the claim,” she said.

Speaking with The Independent outside the courtroom, the lawyer Karpinskaya said the evidence presented by the state prosecution was “highly irregular”, and proved nothing: “Maybe they haven’t made a decision yet about where they are taking the case. But the danger is that when we reach the end of the process, the judge will have forgotten that it’s all junk.”

Already, the trial has come at considerable cost to the defendants and their families.

Serebrennikov, an only child, was this year unable to be by his dying mother’s side. His father, too, is currently suffering ill health, and is isolated from his son, several hundred miles away in Rostov.

Alexei Malobrodsky meanwhile saw his health deteriorate significantly during a year of pre-trial detention. He suffered a suspected heart attack in May, and only afterwards was released from detention. Last week, the trial was interrupted several times following another heart scare, and he remains under close medical supervision.

Karpinskaya says her client’s pre-trial detention was clearly “disproportionate,” and used to push him to give evidence against Serebrennikov, the only real target of the prosecution.

“Someone had it in for Serebrennikov,” she says. “I can’t say who and why, though I have my suspicions. The other defendants are simply collateral.”

The resources being thrown at the case bear little correlation to the alleged sums involved. There are many theories — but little light — about who could be the driving force behind the prosecution. Might it represent an attack on Vladislav Surkov, the once-all-powerful presidential aide and a prominent Serebrennikov backer? Was Vladimir Medinsky, the ultra-conservative culture minister somehow involved? Could Tikhon Shevkunov, Putin’s “personal confessor” be scheming?

The only man who matters, Vladimir Putin, has made several contradictory statements on the case. At one point, he called investigators “fools”, before later suggesting “serious economic crimes” had been committed.

One thing seems certain: The trial has become unusually sensitive for the Russian political system.

Earlier this month, two students in Russia’s leading film school were threatened with expulsion after they began making a film about Gogol Centre and the Serebrennikov affair.

Director Artyom Firsanov told The Independent the school’s management subjected him to several hours of intense questioning. They asked him to stop filming and withdrew permission to use the school’s facilities – allegedly after receiving a call “from above”.

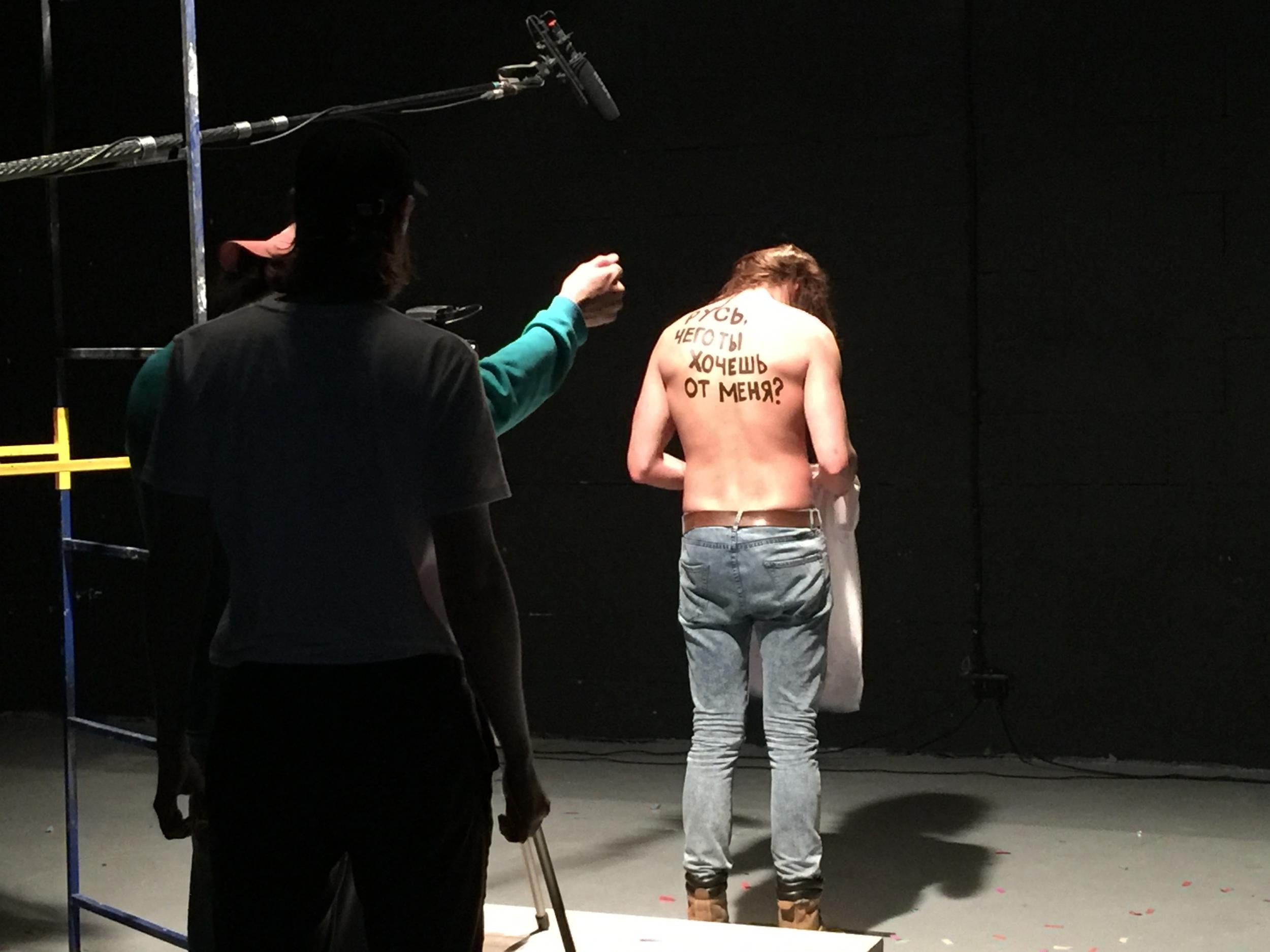

Shooting for Being Kirill Serebrennikov continued nonetheless in a hastily rearranged studio located in a suburban shopping centre. Over the course of a day, more than fifty people turned up to deliver short pieces to camera. Some employed song, while others appeared with portraits of the absent director, his mouth painted over.

The last participant stood simply, with his back to the camera, before removing his t-shirt to reveal a message written across his shoulders.

“Russia, what do you want from me?” it read.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments