The underworld is going freelance: Why The Godfather's Mafia model is no longer viable

A research project into organised crime in Europe reveals a very different picture to the close-knit family ties of the silver-screen classics, as David S Wall and Yulia Chistyakova explain

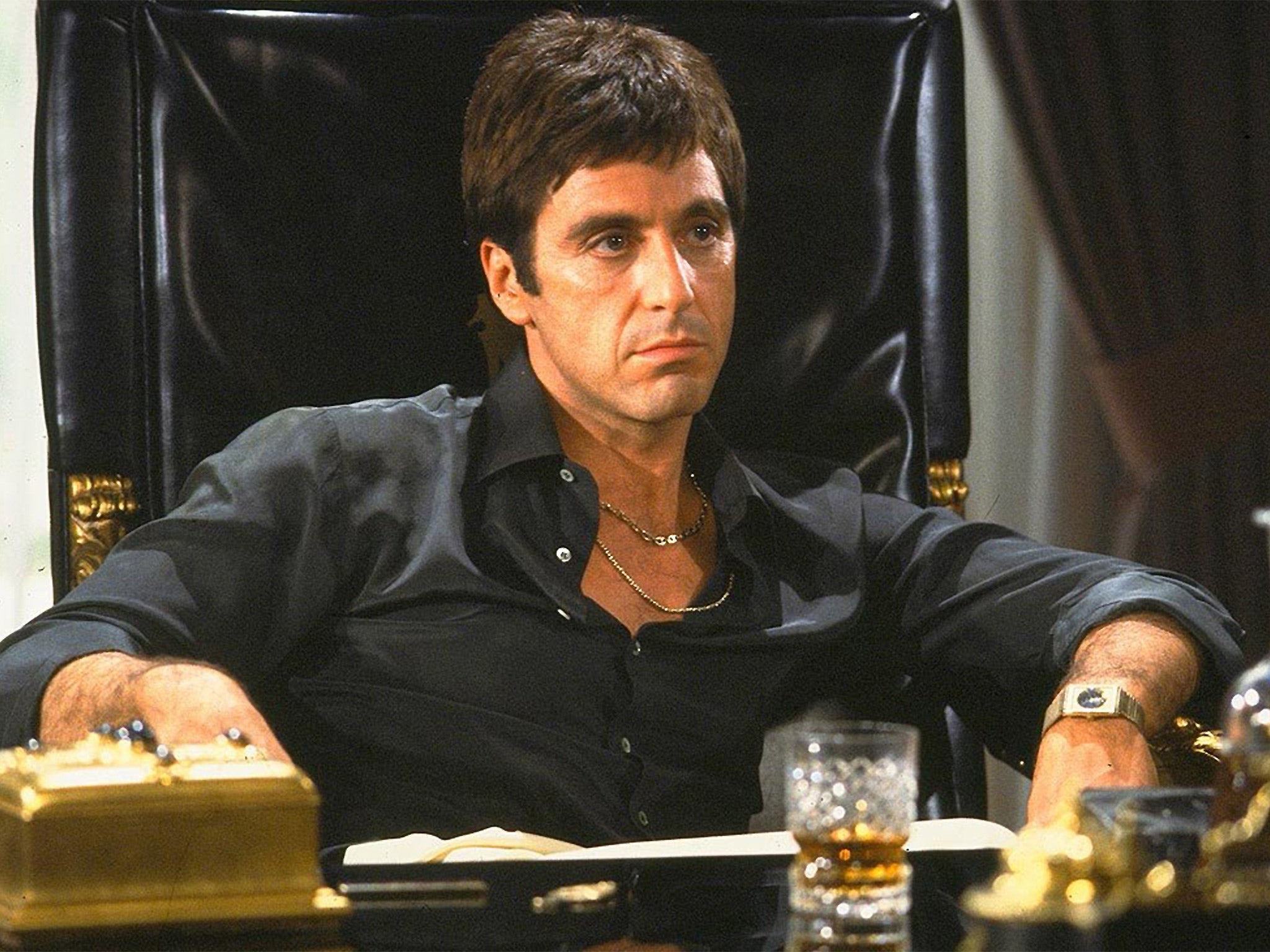

The term "organised crime" instantly conjures up brutal imagery of a crime family going about its day-to-day business to the tune of Coppola's The Godfather. Life began to imitate art, as US and Italian Mafia families (reportedly) copied the mannerisms of the over-stylised characters in the movies.

But this imitation was mostly aesthetic, because research is revealing a very different picture of organised crime to the close-knit family ties of the silver-screen classics, one of a complex and shape-shifting world of career criminals. The recent EU-funded Organised Crime Portfolio research project, to which we contributed, has estimated that organised crime costs the EU economy about €110bn.

One of the key concerns in the UK is the structure of organised crime groups and the extent to which they reflect or differ from the socio-geographically based Mafia groups found in Italy and elsewhere. The picture of organised crime in the UK leans away from the traditional Mafia model towards conglomerations of career criminals who temporarily join with others to commit crimes until they are completed and then reform with others to commit new crimes.

As of December 2013, the number of organised crime groups operating in the UK was estimated by the National Crime Agency (NCA) to be about 5,300, comprising about 36,600 organised criminals. A Home Office study of profiles of organised criminals in the UK has shown that the vast majority (87 per cent) were UK nationals. While the majority had been convicted for drug-related offences (73 per cent), only 12 per cent of them specialised in a particular crime type – most are generalists. Perhaps the most interesting finding of the EU Organised Crime Portfolio project is that if you take the Italian mafia groups, such as La Cosa Nostra, 'Ndrangheta and Camorra, then the pattern of organised crime groups in the UK is roughly similar to the rest to Europe. Most studies characterise them as polymorphous, adaptable and fluid multi-commodity criminal networks.

While kinship and ethnicity remain important factors for group cohesion, multiple cross-ethnic linkages also play an important role and such mixed networks may be more viable, successful, continuous and respected. The evidence points to domestic groups and networks, but there is some indication of activity by foreign-based organised groups operating legal businesses in the UK. These constantly adapting organised crime groups are shifting towards less risky and less violent – but still lucrative – market niches where detection of organised crime is more difficult. Our research shows that fraud, drug trafficking, counterfeiting and tobacco smuggling are currently the largest organised illicit markets in the UK. Other profitable markets are trafficking for sexual exploitation and organised vehicle crime. Alongside traditional markets of organised crime such as drugs and human trafficking, though, there is growing evidence of its presence in the financial sector, renewable energy, and waste and recycling.

Our estimates show that the profits of particular criminal enterprises can vary from tens of thousands to hundreds of millions of pounds. Contrary to popular belief, not all organised crime is associated with vast profits; many offenders just make enough to cover living expenses they "offend and spend", partly an effect of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, which empowers various agencies to seize the profits of crime. When criminals do invest, their main motivation is to satisfy personal and family consumption needs and lifestyle preferences. They may also create illegitimate businesses or use their profits to facilitate further crime such as money laundering, rather than accumulate wealth. The picture of organised crime emerging from the project is that of an evolving, adaptable, trans-national business model which points clearly to the need for a fundamental change in the approach towards policing organised crime in the UK.

The current hierarchical and rigid model we have is more suited to targeting traditional Mafia-type organisations. 21st century organised crime requires a bit more thought.

David S Wall is Professor of Criminology at Durham University. Yulia Chistyakova is a Senior Lecturer in Criminology at Liverpool John Moores University. This article was originally published on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments