The Big Question: Who is Dmitry Medvedev, and what would his presidency mean for Russia?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why is this the question of the moment?

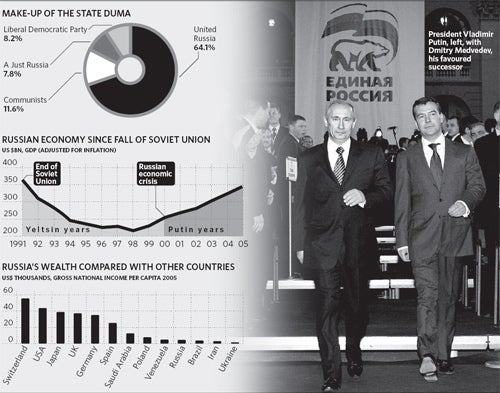

Dmitry Medvedev, one of Russia's two first deputy prime ministers, has been formally nominated by the dominant United Russia party as its candidate for the presidential election next March. He was crowned at the party's congress, held this week in Moscow and, crucially, endorsed by President Vladimir Putin.

In a piece of televisual stage-management clearly designed to send a message of top-level approval and continuity to Russian voters, the two men had entered the hall together and walked briskly towards the platform side by side through the applauding throng of delegates.

Who is Dmitry Medvedev?

He was born in 1965 in St Petersburg, then called Leningrad, to professional parents: his father was a professor and his mother a teacher. He graduated from Leningrad State University in law in 1987, just as Mikhail Gorbachev started the reforms that resulted in the collapse of the Soviet Union, and embarked on a conventional academic career. From 1990, however, he combined his university work with work at Leningrad City Council, then run by the ultra-reformist mayor, Anatoly Sobchak.

He is married, to his childhood sweetheart, Svetlana, who does social work and organises fashion shows for charity. They have a 12 year old son, Ilya.

How did he come to be heir apparent?

At Leningrad City Council, Medvedev worked in the mayor's external affairs team. This was headed by Putin, who had recently returned to work in his native Leningrad after resigning from the KGB. Unlike many of Putin's entourage, he has no security service background, but his association with Putin was vital. In 1999, he followed Putin to Moscow as deputy chief of staff in the administration of the declining president, Boris Yeltsin.

The following year, he ran Putin's presidential election campaign and began his involvement with the state energy and media conglomerate, Gazprom. He became chairman of Gazprom in 2002 and Kremlin chief of staff the following year, in a double recognition that he was a man who could get things done in the way Putin wanted them. In 2005, he was promoted to first deputy prime minister in charge of social programmes.

Is he certain to be the next president?

Given his nomination by United Russia the party that won more than 60 per cent in this month's parliamentary elections and his endorsement by the hugely popular Putin, it is hard to see how he can fail. His main electoral opponent is likely to be Gennady Zyuganov, the head of the Communist Party, whom he would beat hands down. There are, however, other scenarios. A major security emergency, for instance, might increase the pressure for Putin to stay on. One US academic has posited a sequence of events, triggered by the assassination of Putin, entailing a coup by the so-called siloviki a Kremlin faction of hardliners with security connections.

Nor can other plausible candidates be completely excluded, including the other first deputy premier, Sergei Ivanov, or the current Prime Minister, Nikolai Zubkov, both of whom are members of Putin's St Petersburg set. Nominations close next week.

And Garry Kasparov?

The millionaire and one-time world chess champion heads an alliance of disparate opposition parties from extreme left to extreme right called The Other Russia, whose public activities have been heavily circumscribed by the authorities. It has no shortage of funds, but its support is small in part, but not entirely, because of the difficulty any anti-Kremlin group has in getting its message across in Russia today. Kasparov announced last week that he would not stand for president after failing to find a hall to host his nominating meeting.

What sort of a president would Medvedev make?

He is young still only 42 energetic, and determined. He is regarded as being among the liberals in Putin's team, but he has never joined a political party, and is considered non-ideological. Some believe that his non-security background might make him more tolerant of dissent than Putin, and he has said that "no non-democratic state has ever become truly prosperous for one simple reason: freedom is better than non-freedom". At the same time, it would be wrong to get too excited about reports that he enjoys Western rock music. Something similar has been said of almost every Russian leader since Stalin.

What about policies?

He says he will continue "Putin's plan", which envisages a series of major infrastructure projects (railways, airports and power stations) to be undertaken between now and 2020, funded by some of the country's energy windfall. These are enormous undertakings that will require political determination and authority that extends into the furthest regions.

His responsibilities as first deputy premier have included initiatives to reverse Russia's adverse demographic trends and modernise the failing Soviet-era health and education services. Putin improved the pay of doctors and teachers, but has barely made a start on improving systems and facilities.

What about the outside world?

He is seen as more cosmopolitan in outlook than Putin and more business-friendly. Recent hints about listing Gazprom on the New York and Shanghai stock exchanges suggest a desire to integrate Russia further into the global economy that could include reviving Russia's application to join the World Trade Organisation. None of this means, though, that he would not be as staunch a defender of Russian interests, as he sees them, as Putin. Russia's opposition to US anti-missile installations close to its borders, for instance, is likely to continue.

Where will Putin fit in?

Putin has long insisted that he will step down in March, as the Constitution requires, and it is now more certain than ever that he will. But he also indicated this week that he might well accept Medvedev's invitation to be prime minister. In some ways this would suit his temperament he sees himself as more of an administrator than a politician. But it is still by no means certain that he will become prime minister. The plan could just be a device to assuage Russian voters' fears of the unknown in the run-up to the March election, allowing Putin an honourable retirement and perhaps a new career.

Will Russia change if Medvedev becomes president?

Yes...

* He is the next generation after Putin, with less of a Soviet stamp and no KGB associations.

* He will inherit a Russia with higher material expectations than ever, and he will have to take this into account.

* As an elected president he will have the upper hand, even if Putin becomes his first prime minister.

No...

* He will owe his job to his association with Putin, and will be expected to follow where Putin has led.

* Putin's authority is such that the next president will inevitably be in his shadow.

* Russia is so big, backward and unwieldy that it will take more than a change of president to effect significant change.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments