The global machine behind the rise and rise of Sweden’s far right

Former street neo-Nazis enter the corridors of power, bringing with them talk of a culture war where immigrants and refugees are a threat

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

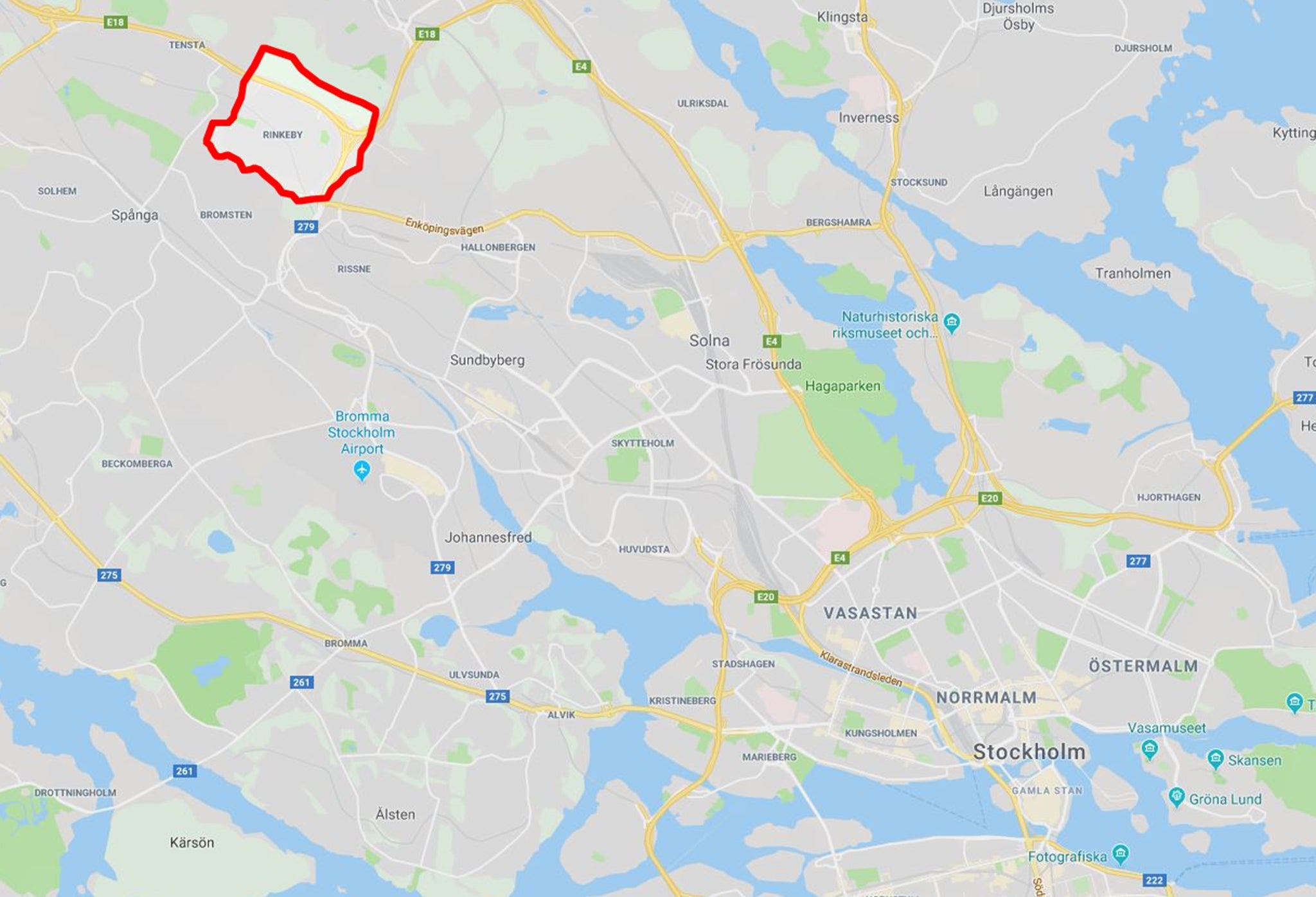

Your support makes all the difference.Johnny Castillo, a Peruvian-born neighbourhood watchman in this district of Stockholm, still puzzles over the strange events that two years ago turned the central square of this predominantly immigrant community into a symbol of multiculturalism run amok.

First came a now-infamous comment by President Donald Trump, suggesting that Sweden’s history of welcoming refugees was at the root of a violent attack in Rinkeby the previous evening, even though nothing had actually happened.

“You look at what’s happening last night in Sweden. Sweden! Who would believe this? Sweden!” Trump told supporters at a rally on Feb. 18, 2017. “They took in large numbers. They’re having problems like they never thought possible.”

The president’s source: Fox News, which had excerpted a short film promoting a dystopian view of Sweden as a victim of its asylum policies, with immigrant neighbourhoods crime-ridden “no-go zones.”

But two days later, as Swedish officials were heaping bemused derision on Trump, something did happen in Rinkeby: Several dozen masked men attacked police officers making a drug arrest, throwing rocks and setting cars ablaze.

And it was right around that time, according to Mr Castillo and four other witnesses, that Russian television crews showed up, offering to pay immigrant youths “to make trouble” in front of the cameras.

“They wanted to show that President Trump is right about Sweden,”Mr Castillo said, “that people coming to Europe are terrorists and want to disturb society.”

That nativist rhetoric — that immigrants are invading the homeland — has gained ever-greater traction, and political acceptance, across the West amid dislocations wrought by vast waves of migration from the Middle East, Africa and Latin America.

In the nationalists’ message-making, Sweden has become a prime cautionary tale. What is even more striking is how many people in Sweden — progressive, egalitarian, welcoming Sweden — seem to be warming to the nationalists’ view: that immigration has brought crime, chaos and a fraying of the cherished social safety net, not to mention a withering away of national culture and tradition.

Fuelled by an immigration backlash, right-wing populism has taken hold, reflected most prominently in the steady ascent of a political party with neo-Nazi roots, the Sweden Democrats. In elections last year, they captured nearly 18% of the vote.

To dig beneath the surface of what is happening in Sweden, though, is to uncover the workings of an international disinformation machine, devoted to the cultivation, provocation and amplification of far-right, anti-immigrant passions and political forces. Indeed, that machine, most influentially rooted in Vladimir Putin’s Russia and the American far right, underscores a fundamental irony of this political moment: the globalisation of nationalism.

The central target of these manipulations from abroad — and the chief instrument of the Swedish nationalists’ success — is the country’s increasingly popular, and virulently anti-immigrant, digital echo chamber.

A New York Times examination of its content, personnel and traffic patterns illustrates how foreign state and non-state actors have helped give viral momentum to a clutch of Swedish far-right websites.

Russian and Western entities that traffic in disinformation, including an Islamophobic think tank whose former chairman is now Trump’s national security adviser, have been crucial linkers to the Swedish sites, helping to spread their message to susceptible Swedes.

The distorted view of Sweden pumped out by this disinformation machine has been used, in turn, by anti-immigrant parties in Britain, Germany, Italy and elsewhere to stir xenophobia and gin up votes, according to the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, a London-based nonprofit that tracks the online spread of far-right extremism.

From Margins to Mainstream

Mattias Karlsson, Sweden Democrats’ international secretary and chief ideologist, likes to tell the story of how he became a soldier in what he has described as the “existential battle for our culture’s and our nation’s survival.”

It was the mid-1990s and Karlsson, now 41, was attending high school in Vaxjo. Sweden was accepting a record number of refugees from the Balkan War and other conflicts. In Vaxjo and elsewhere, young immigrant men began joining brawling gangs, radicalising Karlsson and drawing him towards the skinhead scene.

He took to wearing a leather jacket with a Swedish flag on the back and was soon introduced to Mats Nilsson, a Swedish National Socialist leader.

In 1999, Karlsson joined the Sweden Democrats, a party rooted in Sweden’s neo-Nazi movement. Indeed, scholars of the far right say that is what sets it apart from most anti-immigration parties in Europe and makes its rise from marginalized to mainstream so remarkable.

While attending university, Mr Karlsson had met Jimmie Akesson, who took over the Sweden Democrats’ youth party in 2000 and became party leader in 2005. Mr Akesson was outspoken in his belief that Muslim refugees posed “the biggest foreign threat to Sweden since the Second World War.” But to make that case effectively, he and Karlsson agreed, they needed to remake the party’s image.

They purged neo-Nazis who had been exposed by the press. They announced a zero-tolerance policy towards extreme xenophobia and racism, emphasised their youthful leadership and urged members to dress presentably. And while immigration remained at the centre of their platform, they moderated the way they talked about it.

To what extent the party’s makeover is just window dressing is an open question.

Under Mr Akesson and Mr Karlsson, the party has hosted American white nationalist Richard Spencer. High-ranking party officials have bounced between Sweden and Hungary, ruled by authoritarian nationalist Prime Minister Viktor Orban. Mr Karlsson has come under fire for calling out an extremist site as neo-fascist while using an alias to recommend posts as “worth reading” to party members.

Still, even detractors admit that strategy has worked. In 2010, Sweden Democrats captured 5.7% of the vote, enough for the party, and Mr Karlsson, to enter Parliament for the first time. That share has steadily increased along with the growing population of refugees. (Today, roughly 20% of Sweden’s population is foreign born.)

At its peak in 2015, Sweden accepted 163,000 asylum-seekers, mostly from Afghanistan, Somalia and Syria. Though border controls and tighter rules have eased that flow, Ardalan Shekarabi, the country’s public administration minister, acknowledged that his government had been slow to act.

Mr Shekarabi, an immigrant from Iran, said the sheer number of refugees had overwhelmed the government’s efforts to integrate them.

“I absolutely don’t think that the majority of Swedes have racist or xenophobic views, but they had questions about this migration policy and the other parties didn’t have any answers,” he said. “Which is one of the reasons why Sweden Democrats had a case.”

A Right-Wing Echo Chamber

As the 2018 elections approached, Swedish counterintelligence was on high alert for foreign interference. Russia, the hulking neighbour to the east, was seen as the main threat. After the Kremlin’s meddling in the 2016 U.S. election, Sweden had reason to fear it could be next.

“Russia’s goal is to weaken Western countries by polarising the debate,” said Daniel Stenling, the Swedish Security Service’s counterintelligence chief. “For the last five years, we have seen more and more aggressive intelligence work against our nation.”

But as it turned out, there was no hacking and dumping of internal campaign documents, as in the United States. Nor was there an overt effort to swing the election to the Sweden Democrats, perhaps because the party, in keeping with Swedish popular opinion, has become more critical of the Kremlin than some of its far-right European counterparts.

Instead, security officials say, the foreign influence campaign took a different, more subtle form: helping nurture Sweden’s rapidly evolving far-right digital ecosystem.

For years, the Sweden Democrats had struggled to make their case to the public. Many mainstream media outlets declined their ads. The party even had difficulty getting the postal service to deliver its mailers. So it built a network of closed Facebook pages whose reach would ultimately exceed that of any other party.

But to thrive in the viral sense, that network required fresh, alluring content. It drew on a clutch of relatively new websites whose popularity was exploding.

Members of the Sweden Democrats helped create two of them: Samhallsnytt (News in Society) and Nyheter Idag (News Today). By the 2018 election year, they, along with a site called Fria Tider (Free Times), were among Sweden’s 10 most shared news sites.

Russia’s hand in all of this is largely hidden from view. But fingerprints abound.

For instance, one writer for Samhallsnytt, who previously worked for the Sweden Democrats, was recently declined parliamentary press accreditation after the security police determined he had been in contact with Russian intelligence.

Fria Tider is considered not only one of the most extreme sites, but also among the most Kremlin-friendly. It frequently swaps material with the Russian propaganda outlet Sputnik. The site is linked, via domain ownership records, to Granskning Sverige, called the Swedish “troll factory” for its efforts to entrap and embarrass mainstream journalists.

At the magazine Nya Tider, editor Vavra Suk has travelled to Moscow as an election observer and to Syria, where he produced Kremlin-friendly accounts of the civil war. Nya Tider has published work by Alexander Dugin, an ultra-nationalist Russian philosopher who has been called “Putin’s Rasputin”; Suk’s writings for Dugin’s think tank include one titled “Donald Trump Can Make Europe Great Again.”

Then there is Nyheter Idag. Its founder, Chang Frick — a former Sweden Democrat official who takes a maverick’s glee in his defiance of orthodoxy — readily admits to being a paid contributor to RT. At a pizza shop near his home one afternoon, he pointedly noted that his girlfriend was Russian and, with a flourish, pulled out a wad of rubles from a recent trip.

“Here is my real boss! It’s Putin!” he laughed.

There is another curious Russian common denominator: Six of Sweden’s alt-right sites have drawn advertising revenue from a network of online auto-parts stores based in Germany and owned by four businessmen from Russia and Ukraine, three of whom have adopted German-sounding surnames.

The ads were first noticed by the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter, which discovered that while they appeared to be for a variety of outlets, all traced back to the same Berlin address and were owned by a parent company, Autodoc GmbH.

The New York Times found that the company had also placed ads on anti-Semitic and other extremist sites in Germany, Hungary, Austria and elsewhere in Europe.

Rikard Lindholm, co-founder of a data-driven marketing firm who has worked with Swedish authorities to combat disinformation, dug deeper into the Autodoc network.

Hidden beneath the user-friendly interface of some of the earliest Autodoc sites lay what Mr Lindholm, an expert in the forensic analysis of online traffic, described as “icebergs” of blog-like content completely unrelated to auto parts, translated into a variety of languages. A visitor to one of the car-parts sites could not simply access this content from the home page; instead, one had to know and type in the full URL.

Thomas Casper, a spokesman for Autodoc, said the company had no “interest at all in supporting alt-right media,” and added, “We vehemently oppose racism and far-right principles.”

He said the company’s digital advertising team worked with third parties to place ads on “trusted websites with substantial traffic.” Autodoc, he said, had instituted controls to try to ensure that it no longer advertised on far-right sites.

As for the icebergs, after receiving The New York Times’ inquiry, the company removed what Casper called the “obviously dubious and outdated content.” It had originally been placed there, he said, to improve search engine optimisation.

But Mr Lindholm said that made no sense. “By linking to irrelevant content, it actually hurts their business because Google frowns on that,” he said.

Links Abroad

Another way to look inside the explosive growth of Sweden’s alt-right outlets is to see who is linking to them. The more links, especially from well-trafficked outlets, the more likely Google is to rank the sites as authoritative. That, in turn, means that Swedes are more likely to see them when they search for, say, immigration and crime.

The New York Times analysed more than 12 million available links from over 18,000 domains to four prominent far-right sites — Nyheter Idag, Samhallsnytt, Fria Tider and Nya Tider. The data was culled by Mr Lindholm from two search engine optimisation tools and represents a snapshot of all known links through July 2.

As expected, given the relative paucity of Swedish speakers worldwide, most of the links came from Swedish-language sites.

But the analysis turned up a surprising number of links from well-trafficked foreign-language sites — which suggests that the Swedish sites’ rapid growth has been driven to a significant degree from abroad.

Many are well known in American far-right circles. Among them is the Gatestone Institute, a think tank whose site regularly stokes fears about Muslims in the United States and Europe. Its chairman until last year was John Bolton, now Trump’s national security adviser.

Other domains that linked to all four Swedish sites included Stormfront, one of the oldest and largest American white supremacist sites; Voice of Europe, a Kremlin-friendly right-wing site; a Russian-language blog called Sweden4Rus.nu; and FreieWelt.net, a site supportive of the AfD in Germany.

Building a Coalition

In February, the Sweden Democrats’ Karlsson strode into a Washington-area hotel where leaders of the American and European right were gathering for the annual Conservative Political Action Conference.

At the conference Karlsson hoped to learn about the infrastructure of the American conservative movement, particularly its funding and use of the media and think tanks to broaden its appeal. But in a measure of how nationalism and conservatism have merged in Trump’s Washington, many of the Americans with whom he wanted to network were just as eager to network with him.

Karlsson had flown in from Colorado, where he had given a speech at the Steamboat Institute, a conservative think tank. That morning, Tobias Andersson, 23, the Sweden Democrats’ youngest member of Parliament and a contributor to Breitbart, had spoken to Americans for Tax Reform, a bastion of tax-cut orthodoxy.

Now, they found themselves encircled by admirers like Matthew Hurtt, director for external relationships at Americans for Prosperity, part of the billionaire Koch brothers’ political operation, and Matthew Tyrmand, a board member of Project Veritas, a conservative group that uses undercover filming to sting its targets.

Tyrmand, who is also an adviser to a senator from Poland’s anti-immigration ruling Law and Justice party, was particularly eager. “You are taking your country back!” he exclaimed.

Karlsson smiled.

New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments