The daring tales of the Spaniards who fought for the SAS in the Second World War

Graham Keeley speaks to British Army officer Sean Scullion about his new book, detailing the bravery of Spanish soldiers fighting for the British against the Nazis

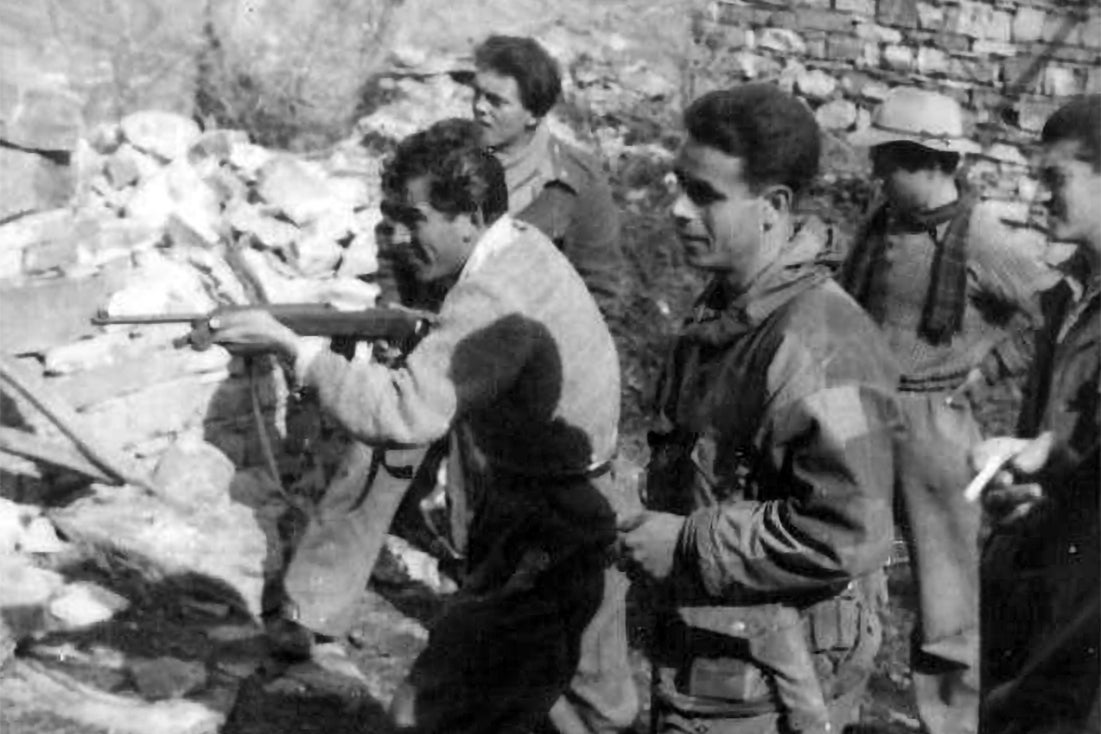

In the final days of the Second World War, commandos from the SAS parachuted behind enemy lines to attack a crack German mountain unit in an operation which seems like something out of the pages of a novel.

Rafael Ramos Masens killed six Nazi troops and carried his wounded captain to safety. His actions earned him the Military Medal for “notable bravery during and after the attack” behind enemy lines. Before he reached the attack in Italy, Ramos had walked about 125 miles and fought in two other battles.

This is just one of many extraordinary tales of hundreds of Spaniards who fought across Europe and beyond for the British Army, to defeat fascism.

Spanish soldiers fought in every theatre of war, including Tobruk, Crete, Salerno, Normandy, Arnhem and the Ardennes. When victory over Germany finally came, however, Spaniards who had risked their lives were disappointed that the Allies did not try to bring down the Spanish dictator General Francisco Franco.

Their story is captured in dramatic fashion in Churchill’s Spaniards, published this month, which relates the heroism of these men, who were already veterans of the Spanish civil war when they enlisted for Britain.

Sean Scullion, a lieutenant colonel in the British Army, who is based in the Netherlands for Nato, spent eight years researching the stories of about 1,200 Spaniards who fought for Winston Churchill. The SAS had at least nine Spanish troopers.

Two of Ramos’s comrades, Justo Balerdi and Francisco Gerónimo took part in another operation with the secretive army unit.

Balerdi lost his life when he was shot in the head. He was buried under the nom de guerre, R Bruce, after Robert the Bruce. He chose the name to avoid being sent back to Spain if he was captured or to escape summary execution under Hitler’s 1942 “commando order”, which said that any Allied commando must be killed when captured.

Geronimo, who was known as Frank Williams, wanted to be called Francis Drake but was not allowed to use the name of the English national hero.

Another remarkable character was Angel Camarena. Before the Spanish civil war, this poetry-writing free spirit worked as a driver for General Franco and played with the future dictator’s daughter. But after the civil war broke out, he was condemned to death as a Republican. As he was about to be shot by firing squad, he jumped off a prison ship and was picked up by a passing British ship, only to be returned to the Spaniards on the condition he was not executed.

After five years in prison in Morocco, he was released, joined the Allies and was recruited by the SAS.

“Camarena becomes a good friend of Geronimo and after the war they end up living on the same street in Swansea, of all places,” Scullion says.

“He was involved in the SAS operation which was one of the most famous and most dangerous, Operation Loyton. A lot of the SAS troopers were betrayed by infiltrators as they were close to the German border. I think over 30 SAS members were murdered by the Germans. He survived that. He was another hard as nails guy.”

Ramos, who was born in Barcelona, had fought on the Republican side in the civil war in the battle of the River Ebro in 1938. After being captured, he escaped to France. His story is typical of other countrymen who were forced to flee Spain after the victory of Franco’s forces in the civil war in 1939.

Some ended up in refugee camps in southern France and then enlisted in the French Foreign Legion to fight the Germans after the Nazi invasion in 1940. But when France fell, many were anxious to change armies and fight for Britain as they respected British discipline.

A second wave of Spanish troops joined the British in 1942 after the liberation of North Africa by Allied soldiers. Some joined the SAS and took part in long-distance desert forays with this elite unit.

The No 1 Spanish Company of the Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps was the only exclusively Iberian company.

Some were judged “hotheads” by the British, who disdained the lack of discipline of a few Spanish troops. However, Scullion notes, what some Spaniards lacked in discipline, they made up for in bravery.

“They were not generally great marksmen,” he writes. “But they loved the feel of cold steel in their hands: knives and bayonets.”

After the war, many former soldiers formed exile groups in Britain.

“Some of them settled down, married local girls or Spanish girls or got their families over from Spain. They formed ex-servicemen associations and carried on the fight [against Franco] from there,” says Scullion, who speaks Spanish fluently as he spent part of his youth in Madrid.

Scullion’s meticulous research involved interviewing the families of 70 soldiers – but sadly all had died before he could reach them. So he had to separate fact from family myth.

For Scullion, this was simply a tale which needed to be told: “It is a fascinating story.”

‘Churchill’s Spaniards’ is published by Helion & Company

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments