Silvio Berlusconi obituary: The bunga bunga party loving billionaire who was the king of comebacks

The flamboyant tycoon and politician has passed away aged 86 after a colourful life that took in sex scandals, tax fraud, and four stints as Italy’s prime minister

Silvio Berlusconi, the boastful billionaire media mogul who, despite scandals over his sex-fuelled parties and allegations of corruption, was Italy’s longest-serving prime minister, has died at the age of 86.

A one-time cruise-ship crooner, Berlusconi used his television networks and immense wealth to launch his long political career, during which he inspired both loyalty and loathing.

To his admirers, the multiple-time premier was a capable and charismatic statesman who sought to elevate Italy on the world stage. To his critics, he was a populist who threatened to undermine democracy by wielding political power as a tool to enrich himself and his businesses.

Born in 1936 in Milan to a bank clerk father and housewife mother, he attended a Catholic college, where he began a complicated relationship with the Church, which supported him until the mounting allegations of sleaze “superseded the limits of decency” in the view of at least one weekly Catholic newspaper.

His capacity to entertain emerged early when he worked on cruise ships and played bass with a band, performing George Gershwin hits like “I Got Rhythm” in the dancehalls of Milan before being sacked for devoting more time to flirting with the audience (“marketing and PR”, he called it) than playing music.

After graduating in law, Berlusconi turned down a job as a cashier at the bank where his father had worked in order to strike out as a property developer.

His ambition was notable. To pull off one make-or-break deal, he persuaded a secretary to tell him when her pension-fund-director boss would be taking a seven-hour train journey so as to ensure that he could sit in the seat next to him. Later, when the flight path over his Milano 2 residential development proved a deterrent to buyers, he had alternative routes opened.

A modest plan to make his homes more attractive by offering a local cable TV service, Telemilano, which showed light entertainment and reruns of American soap operas such as Dallas, grew into a network of local channels until, by the end of the 1980s, his trash TV empire of game shows and barely clothed hostesses came to dominate the Italian airwaves.

As well as hauling in advertising revenue, Berlusconi’s channels allowed him to give favourable coverage to friendly politicians who helped him protect his commercial interests, which now included publishing houses and the football team AC Milan. When he entered politics himself, these contacts would prove indispensable.

The “Clean Hands” corruption inquiries that took out a generation of Italian politicians eventually provided the motivation for that move. Power, he reasoned, would not only protect himself from prosecutors but allow him to defend his businesses.

Headline-grabbing proposals included a million new jobs and lower taxes. A political outsider positioned as an enemy of the establishment, Berlusconi was in many ways a prototype for Donald Trump.

Running a successful Serie A side like the “Rossoneri” was one of his main qualifications for high office, he felt. When challenged by an economist over his tax plans, he replied: “How many intercontinental [football cups] have you won?”

In 1994, he took 21 per cent of the vote in the general election and found himself prime minister, beginning a two-decade domination of Italian politics through which he shamelessly advanced his own interests.

His personal lawyers, now on the state payroll as MPs, spent their time drawing up laws to get him out of trouble, including immunity from prosecution for the prime minister and a tax amnesty that saved his company €120m (£103m). His communication minister, meanwhile, amended competition rules, allowing him to retain his media empire.

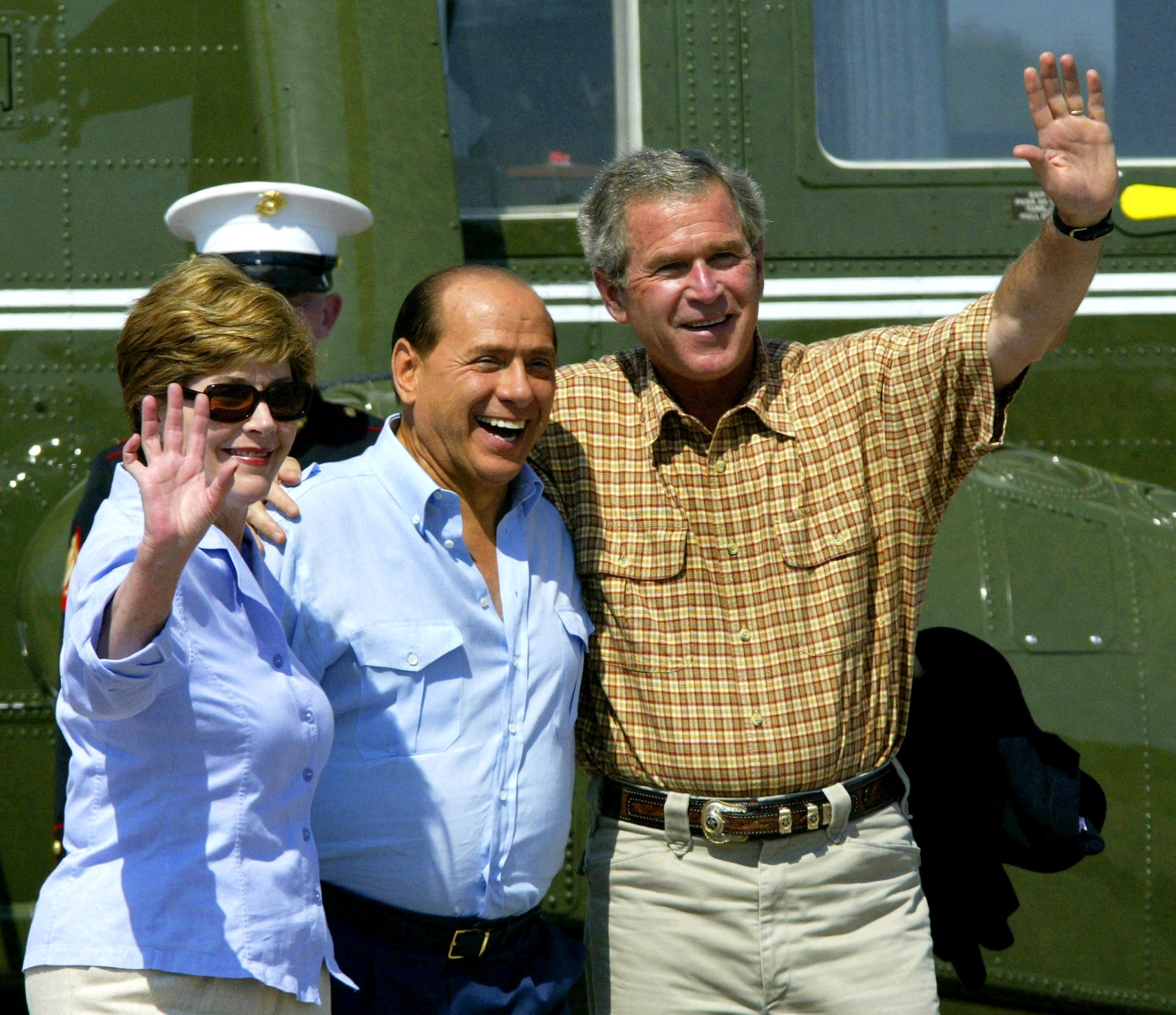

His calling to international relations was evident when he made himself foreign minister as well as prime minister, wooing leaders such as Tony Blair and Putin by inviting them to his James Bond-esque Sardinian villa, which had its own fake volcano. Cherie Blair described her evening there as the best of her life.

But gaffes such as calling America’s first Black president, Barack Obama, “suntanned” and suggesting that a German MEP should play a concentration camp guard made him an international laughing stock. His standing took a further hit in 2009 when his second wife, Veronica Lario, publicly accused him of “frequenting minors”.

When a 17-year-old Moroccan nightclub dancer known as Ruby the Heartstealer, who had been arrested for a petty crime, told police she knew Berlusconi, the claim set in motion a chain of events that would bring about the mogul’s downfall.

Ironically, if Berlusconi had not interceded, claiming she was the niece of Hosni Mubarak, the Egyptian despot, the case might have ended there.

Investigators, their hackles raised by Berlusconi’s meddling, discovered that a harem of showgirls and models regularly visited his villas for sex parties, where they received lavish gifts and envelopes of cash. The drip-feed of salacious details appalled even Italy, where it is less of a taboo for rich men to have mistresses. Thousands took to the streets in protests that expressed women’s frustration at their humiliating role in Berlusconi’s Italy.

But, ultimately, it was not the “bunga bunga” parties that undid him, but his inability to cope as Italy’s debt reached unsustainable levels in 2011, when he was forced to resign in favour of technocrats.

Out of office, he remained in the spotlight thanks to his own media empire and as the defendant in dozens of trials, throughout which he claimed he was the victim of a plot by a left-wing judiciary.

After years of wriggling out of every writ, his eventual conviction for tax fraud in 2014, and subsequent sentencing to community service in a home for Alzheimer’s sufferers, represented rock bottom – but, as usual, Berlusconi proved irrepressible, entertaining residents with bingo games and singalongs – a revival of his old cruise-ship act.

His final years went some way towards rehabilitating his image. He became the oldest member of the European parliament, his centrist pro-European politics far preferable, in the eyes of German chancellor Angela Merkel, to the dangerous populist ideas that were surging in Europe.

When, in February 2021, his party joined a government led by that most establishment of figures, the former European Central Bank chief Mario Draghi, his triumphant comeback was complete.

His return to government represented an unlikely final twist in the story of a figure who had risen from selling electric hairbrushes to being the richest and most powerful man in Italy and a object of global fascination as (depending on your point of view) a media mogul, marketing genius, football club owner, political trailblazer, womaniser and showman.

For every Italian that hated him for his monopolistic control of the media and abuse of power, there was another who admired his business acumen and was amused by his lowbrow larks. As the writer Curzio Malaparte wrote, Berlusconi’s qualities and defects “are the qualities and defects of all Italians”.

Berlusconi is survived by 12 grandchildren and five children: Pier Silvio, Marina, Barbara, Eleonora and Pierluigi.