San Marino stokes envy with speedy Russian-supplied vaccine campaign

Seeking emergency help, the micronation turned to Russia for help, a batch of Sputnik V doses arrived and now the entire adult population expects to be inoculated by the end of May, write Chico Harlan and Stefano Pitrelli

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Just weeks ago, the nation of San Marino was in a panic. It stood as the lone country in western Europe without a supply of coronavirus vaccines.

Its hospital employees, still unprotected, were threatening to not enter Covid wards. One parliamentarian called the situation dangerous. Another said the long wait for vaccines was costing lives every day.

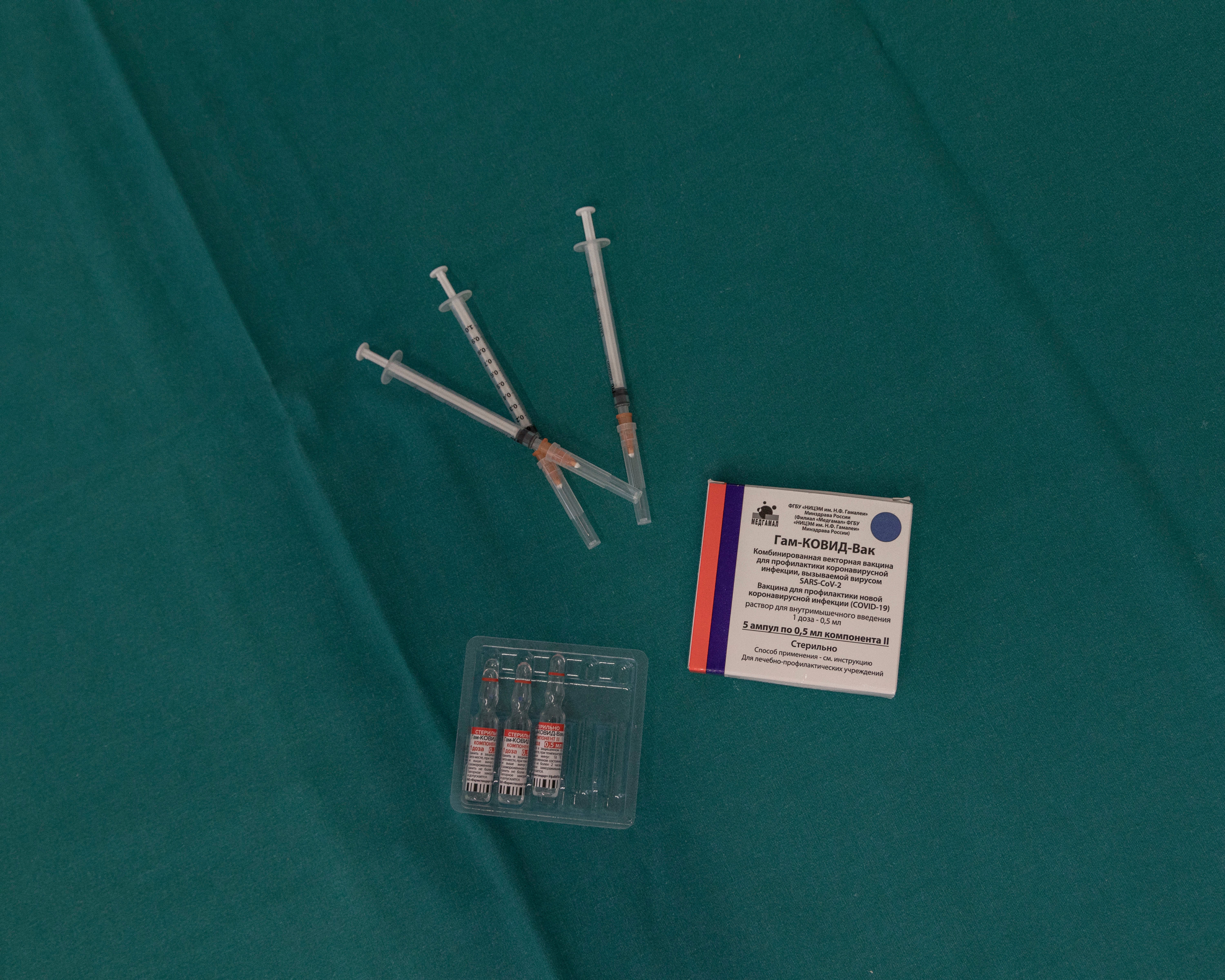

San Marino’s solution, the country’s leaders now say, was driven by that moment of alarm. Seeking emergency help, it turned to Russia and Russia swiftly obliged. An initial batch of Sputnik V doses was soon on the way, escorted by police. Health care workers received the first jabs. San Marino now expects to cover its entire adult population of 29,000 by the end of May.

“We simply made a choice out of necessity,” foreign minister Luca Beccari says.

Read More:

But in easing its own vaccine crisis, this hilltop micronation – which is not a member of the European Union – has become a foil for a much larger crisis playing out beyond its borders. While San Marino has raced ahead with a vaccine not authorised by the EU, Italy – and much of the rest of Europe – has moved at a crawl, with a problem-plagued inoculation drive that has prioritised equitable access across the bloc’s members but prolonged the period of lockdowns, economic suffering and apprehension.

In the shuttered “red zone” Italian regions that surround San Marino, the tiny republic has suddenly become the example of a go-it-alone approach, with implications for both geopolitics and local jealousies. Some politicians – as well as mayors of towns near San Marino – say Italy, too, should be considering the state-made Russian vaccines. Meanwhile, hundreds of anxious Italians have attempted, in vain, to book appointments in San Marino for Sputnik V. Some have tried to enter false San Marino ID numbers in an online system.

The EU, which acquires and authorises vaccines on behalf of its members, is reviewing Russia’s Sputnik V, but the process is likely to take months

“Almost everybody asks me, ‘Can I get it, too?’” says Bruno Frisoni, 76, a San Marino resident. “I tell them it’s not possible.”

For the moment San Marino’s vaccine strategy has created a strange alternate bubble in the Italian countryside, where one’s fortune in the pandemic hinges on national identity.

On both sides of the barely noticeable border between San Marino and Italy, people speak the same language, eat the same stuffed pastas, use the same currency. People from both sides cross to the other for work. The economies are deeply connected, too: In normal times, tourists break away from the Italian Adriatic beaches for day trips to San Marino, whose territory is a mix of medieval fortresses, perfume shops and duty-free electronics stores.

But now, deep into the pandemic, there is a critical difference, even as the virus again surges on both sides of the border. San Marino has administered at least one dose to 27 per cent of its people and could eventually emerge as a protected enclave while other parts of the Continent are still fighting the worst of the virus. In Italy, where 12 per cent of people have received at least one dose, many young people will be waiting long into the summer or autumn for their jabs, a delay amplified by questions about the safety of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine. The EU, which acquires and authorises vaccines on behalf of its members, is reviewing Russia’s Sputnik V, but the process is likely to take months.

“I applaud San Marino,” says Domenica Spinelli, the mayor of Coriano, a town 10 miles away. “They found the Plan B that Europe doesn’t have.”

Even before the vaccine doses arrived, San Marino had been something of a pandemic aberration. With the state’s coffers empty, unable to offer subsidies to shuttered businesses, San Marino was often reluctant to follow Italy into hard lockdowns. When Italy required restaurants to close at 6 pm, San Marino’s stayed open until midnight; now the Italian ones are shuttered all day; San Marino’s still serve lunch.

Still, it had been San Marino’s intent – at least initially – to rely entirely on Italy for its vaccines. In January, it signed a deal in which Rome agreed to redirect one of every 1,700 Europe-supplied doses. That seemed to ensure San Marino would vaccinate at whatever pace the EU would. The agreement, though, required not just a sign-off from Italy but also from Brussels and the vaccine providers. Paperwork delayed the arrangement by nearly two months.

“Once the delays began, we found ourselves dealing with a very strong protest from the citizens,” said Health Minister Roberto Ciavatta. “We needed to offer solutions.”

San Marino considered options aside from Sputnik V. But Chinese-made vaccines had no peer-reviewed studies showing how well they worked. India’s, too, felt like a “leap into the dark”, Ciavatta says. Sputnik V had an advantage for several reasons: A report in The Lancet showed the vaccine was 91.6 per cent effective in preventing symptoms of Covid-19 and fully effective in stopping severe cases, giving it nearly the efficacy of those produced by Moderna and Pfizer. Plus, it was relatively cheap – at roughly 72p per dose. Its design – an adenovirus vector – made it similar to vaccines from AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson.

Because San Marino has no drug regulator equivalent to the European Medicines Agency, it simply put the question about Sputnik V’s use to a small bioethical committee.

The members gave Sputnik V the green light.

The rollout – with a Russian TV documenting one early day – made San Marino a pandemic outlier in a new way: it has become the lone western European county to authorize Sputnik V.

Though more than 50 countries are now issuing Sputnik V jabs, the other users in Europe are closer to Russia’s geographic sphere – Serbia and Moldova, for example. Among EU members, Hungary is the only one to have authorised use. Slovakia and the Czech Republic have also broken away from the EU’s unified purchasing arrangement and acquired Sputnik V for their populations; Austria is considering a similar step. Some other western European countries, including Germany and Italy, have said they would be happy to use Sputnik V but with the caveat that it first should be approved by the EU’s regulator.

Sputnik V’s production capacity is small enough that countries would have to set up their own manufacturing hubs to use the vaccine on a mass scale. For now, Russia seems to be best off sending doses to countries such as San Marino, where it can make a big splash with even a small quantity of the product. Russia initially provided 15,000 doses – enough for 7,500 people – but San Marino officials say they will probably soon ask for more.

Igor Pellicciari, a professor at the University of Urbino in Italy, who is also a San Marino ambassador and consulted on the Sputnik V deal, said Moscow is deploying the vaccine as a soft power tool, using exports to expand its influence, including in places where it is viewed warily or under sanctions.

“Like vodka in the 1970s,” he said. “This is the strongest asset Russia has.”

San Marino’s top health official, Agostino Ceccarini, says the vaccine is clearly working. Nobody among the more than 7,000 who have received it has ended up with a grave form of Covid-19. Though the country is now also receiving a trickle of Pfizer doses from its agreement with Italy, Sputnik V accounts for 85 per cent of San Marino’s administered shots.

Ceccarini says the Russian doses have kept the nation’s single hospital from “exploding” because they have protected the older population at a time when a severe third wave, driven by a more transmissible and probably deadlier British variant, has caused more dire cases among the young.

Despite its vaccination campaign, San Marino’s situation remains critical. The country’s death rate, though similar to northern Italian regions, is technically the highest of any nation in the world, according to Johns Hopkins University in the US. Ten people have died in San Marino over the past month, bringing the overall toll to 84 – deaths that mostly come in a crammed ward on the hospital’s fourth floor.

On the ground level, nurses unpack the day’s Sputnik V doses.

“Let’s hope this can bring the pandemic to an end,” says patient Anna Maria Toccaceli, 75, minutes after receiving her second dose.

“We were lucky,” said Daniele Ceccoli, 74. “This virus, it’s still something very explosive.”

Just beyond San Marino’s borders, the same pressures are at play, and hospitalisations are at the highest point during the pandemic. The difference in Italy is the sense that an endpoint still feels out of reach.

At a hotel that he owns 10 miles from the border, Italian Gianmaria Castaldo says people were losing much of the hope that surged with the beginning of Europe’s vaccination campaign in December. Few have got shots, he says, and “everybody I know is infected” – including himself and he was still in isolation after recovering.

Read More:

He says he looks at San Marino with envy. He worries that the slow pace of vaccinations in Italy is endangering the tourist season. His hotel couldn’t survive another year like the last – when he earned a quarter of the usual income. He says he worries, above all, about his father, Vittorio, 59, with whom he shares the business, which includes three other properties. Vittorio has a lung condition and yet has been travelling to the other hotels across northern Italy, with no vaccine appointment in sight.

Castaldo says he didn’t really care what vaccine he or his father got, so long as it came quickly.

“If the solution is a Russian vaccine, let’s just take it,” he says.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments