Inside Olenivka, the Russian prison camp where Ukrainians vanish

The Missing: Last month an attack on Olenivka killed more than 50 people. It was the latest in a long line of atrocities at the prison camp, where The Independent has uncovered evidence of potential war crimes including torture, disappearances and forced labour, reports Bel Trew from Dnipro, Kyiv and Warsaw

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

In a field whipped hard by frost, separatist soldiers handed their three Ukrainian captives a shovel each and ordered them to dig their own graves.

The three men – all civilian humanitarian volunteers – had been stopped at a checkpoint while trying to rescue family members from the besieged city of Mariupol. The soldiers, from the Russian-backed Donetsk People’s Republic, took them blindfolded to a patch of fresh soil beside two neat crosses.

“They told us the guys buried there had also said they were volunteers but, when their mobiles were checked, they were ‘military’,” says Arkady, a 31-year-old professional climber, describing the start of his ordeal in March.

It would lead to him being disappeared for more than 100 days in what was then a little-known prison called Olenivka.

“They wouldn’t say what happened to the people buried there,” Arkady continues shakily. “They just kept repeating, ‘Now those two men are sleeping. Keep digging.’”

Streaming now on Independent TV – Bel Trew’s exclusive documentary

This was just a few weeks into Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Arkady, from Mariupol, says he and two friends had been attempting their second trip into the strategic coastal city to rescue relatives.

Stopped by soldiers, they were taken to an abandoned house where they were beaten, forced to sleep in a pit outside in sub-zero temperatures, starved, and for two days made to dig their own graves.

“They kept threatening to kill us; we didn’t know if they were going to go through with it. We just kept digging,” he says.

Finally, the men were spared execution and instead were hooded, handcuffed, beaten, and shuttled between several overcrowded, squalid detention centres.

Eventually they were interned in Olenivka, just south of the occupied city of Donetsk.

Among the thousands of male and female inmates held in the detention centre over the course of the conflict so far were the Ukrainian soldiers who in May surrendered to Russia after a stand-off at Mariupol’s Azovstal steel plant – including, say witnesses, British citizen John Harding.

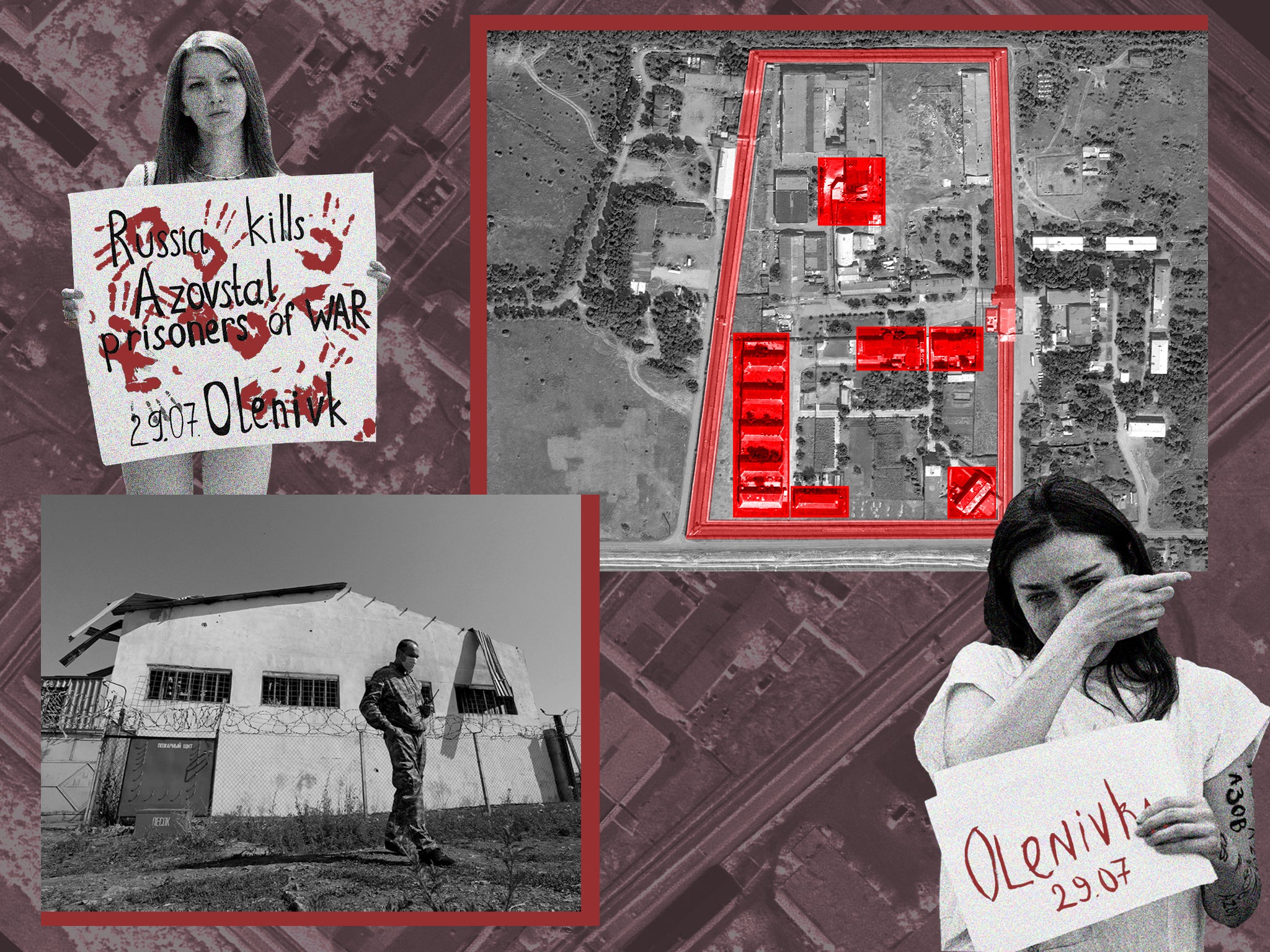

The dilapidated, sprawling facility was unknown internationally until the morning of 29 July, when an explosion killed at least 50 Ukrainian prisoners of war; Russia and Ukraine have blamed the attack on each other.

Civilian internees say that, once they were captured, they had no direct communication with the outside world.

“My mother didn’t know anything for nearly a month,” Arkady, who was released a few weeks ago, tells The Independent. She found out only through someone else who had been released.

Oleksiy, head of an IT company before the war, was also arrested, separately, while trying to rescue civilians from Mariupol. He says he lost contact with his family “from day one”. “We were never charged with anything official,” he says. “We just vanished.”

‘Extremely disturbing allegations’

Russia has vehemently and repeatedly denied that its forces, or the separatist troops it backs, have violated international law in Ukraine. It has instead accused Kyiv of deliberately staging apparent war crimes to besmirch Moscow’s reputation and win Western support.

But a month-long investigation by The Independent has revealed evidence of possible violations of international law and potential war crimes, including torture, enforced disappearances, arbitrary detention and forced labour.

The Independent conducted more than a dozen interviews with recently released civilian detainees and with family members of those still believed to be held in Olenivka, as well as with activists held and tortured in detention centres in other southern cities, Ukrainian officials, and international and local rights groups that are monitoring the missing.

The testimonies also cast doubt on Moscow’s version of the events of 29 July: that Ukraine had rocketed its own PoWs in Olenivka to silence them about crimes Kyiv had committed.

Allan Hogarth, Amnesty International UK’s head of policy and government affairs, said the testimonies contained “extremely disturbing allegations” of acts that, if proved to have taken place, would be likely to constitute war crimes.

“The Russian military authorities must urgently investigate them. Under the Geneva Conventions, captured combatants and other protected persons should be treated humanely at all times,” Mr Hogarth said.

“Enforced disappearance, the denial of food and water, forced labour and, of course, any kind of physical mistreatment are all serious breaches of international humanitarian law and would likely constitute war crimes.

“We’re deeply concerned about these appalling reports and the possibility that Russia and its proxies in the Donetsk People’s Republic are committing widespread war crimes against hundreds – and possibly more – [of] prisoners being held in terrible conditions.”

Human Rights Watch did not comment directly on the findings, but has documented dozens of cases of torture, unlawful detention and forcible disappearance of civilians in the occupied south of the country.

Rachel Denber, deputy director of the Europe and Central Asia division, said that while the laws of war do allow warring parties to intern civilians in non-criminal detention if they pose a serious threat to security, this does not give them “carte blanche” for abuse.

Little is known about Olenivka – information is tightly controlled – but it is understood that, on average, about 2,500 Ukrainians are held at the facility at any one time. According to officials and detainees, the prison was built to hold just half that number.

Lyudmyla Denisova, Ukraine’s former ombudsman for human rights, claims that at some point there may even have been as many as 5,000 citizens detained there. Among them were around 1,500 defenders of Mariupol who surrendered in May, according to Arkady Zhorin, the former commander of the Azov Regiment.

The Independent understands there are currently around 100 interned civilians, including a pregnant woman, almost all of whom were arrested at checkpoints or during what is called the “filtration process” in and around Mariupol.

Three former detainees we interviewed said that, in May, they had briefly met and talked to British citizen John Harding, originally from Sunderland, who had been fighting with the Azov Regiment when he was captured by Russian proxies.

They said he appeared confused and that he was suffering from memory loss due to an explosion shortly before capture.

All four former prisoners we spoke to were subjected to multiple beatings and interrogations on arrival, denied access to sufficient food and water, and made to live in overflowing squalid cells without electricity or running water in the depths of winter.

They said they were also forced to renovate several wings of the facility without compensation, which could amount to forced labour, another potential crime.

They described witnessing military PoWs being beaten with metal rods, wooden sticks and the barrels of guns. One of the civilians was put in “disciplinary” solitary confinement for three days after he questioned why he was being held.

Olenivka was thrown into the spotlight because of the 29 July explosion which, according to Russia, killed 53 soldiers – most of whom had surrendered in May after an 80-day siege at the sprawling Azovstal iron and steel works.

Russia has blamed the deaths on Ukraine, claiming Kyiv used a US-supplied HIMARS (high-mobility artillery rocket system) in a bid to stop its troops revealing the alleged crimes they had committed.

But the Ukrainians have said it was a deliberate “false flag” attack to besmirch Kyiv and cover up abuses committed by Russia and its proxies against Ukrainian citizens being held in prison.

American officials agree, telling media outlets that intelligence shows Moscow putting together fabricated evidence to implicate Ukraine. United Nations chief Antonio Guterres has announced a fact-finding mission into the incident, but there is little hope of the truth emerging.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) said last week it had still not been granted access to the PoWs affected by the attack on Olenivka. Staff were allowed to visit the location twice in May, but the ICRC said that at that point they were not permitted direct access to PoWs individually, something enshrined in the third Geneva Convention.

“I remember the Red Cross visiting once, but they were only allowed to visit the areas we had done up and rebuilt,” says Philip, another former civilian prisoner of Olenivka.

Arkady says they were made to clean the prison whenever there were “special” visitors. “When journalists or the Red Cross came, we were finally given decent food for once. Everything had to be spotless.”

‘They take you to this place and crush you’

The prisoners of Olenivka nicknamed it the “welcome party”. Eyes taped, black bin bags over their heads, they were dragged into a basement in Starobesheve, a town about 18 miles southeast of Olenivka.

There, at the height of winter, on freezing concrete, they were forced to their knees in the stress position for an hour and a half. Three civilians interviewed by The Independent say they were beaten almost unconscious as the Russian soldiers screamed questions and insults at them.

Occasionally the soldiers pressed the cold barrels of rifles to their heads, threatening to shoot. According to ex-detainees, most of those held by Russian and separatist forces at checkpoints around Mariupol were subjected to this routine before they were eventually delivered to Olenivka, where they were again forced to endure another “welcome party”.

“They are like receptions for us,” says Oleksiy, who was first picked up on 28 March at a checkpoint near Nikolski, a northwestern entrance to Mariupol. “We could hear the sounds of gunfire, they were threatening us with guns.”

“At points we could hear the screams of others being tortured,” adds Vitaliy, a truck driver who had teamed up with Oleksiy just the day before they set off for their ill-fated trip. “They told us, ‘The desire to be volunteers will be beaten out of you.’”

Philip, an entrepreneur before the war, was arrested separately on the same day as Vitaliy and Oleksiy while trying to leave Mariupol with rescued civilians. He describes the same treatment.

He says that a month into his detention at Olenivka, he was held in solitary confinement for three days on the ground floor of “DIZO” – a two-storey “disciplinary” block in a southeastern corner of the facility.

There, Philip says, he was beaten and starved. “They take you to this place to humiliate and crush you,” he adds. “I kept asking the guards, what had I done? I don’t know why I was there. I am a civilian, I was never charged with anything or accused of anything.”

All four men say that, despite the abuse, they were treated far better than the Ukrainian soldiers.

“Before the Azov Brigade arrived in May, the beatings of the PoWs would take place in front of our eyes. We saw how bad it was,” Oleksiy says, describing ferocious attacks in which PoWs would collapse.

After hundreds of Azov fighters arrived, they shifted the torture rooms to DIZO. “We were told they would beat them using guns, their legs, wooden sticks and metal rods. Whatever they had to hand,” Oleksiy adds.

‘At least I knew he was alive’

They slept at night crushed with 20, even sometimes as many as 50 people to a cell intended for no more than six inmates. The detainees say they would sit crouched on the concrete floor, taking turns to rest.

In the corner of the room, where the lights were never switched off, was a prison toilet. But since at that point Olenivka had no running water, it was just a spewing vat of sewage.

At first they would be given only two litres of drinking water and a piece of bread a day to share between them, says Oleksiy. And so they had to improvise.

“We managed to secure another plastic bottle of water. Whenever we had the chance, when we were sent out to work, we filled it with water we stole,” he says.

All four former inmates say Olenivka was an abandoned wreck when they arrived. “When we got to Olenivka there were no beds, no utensils for cooking. Few of the buildings had windows, the walls were broken, there was no electricity. It was a nightmare in the cold,” explains Philip.

“The guards put us to work painting the walls and windows of the barracks, cleaning and scrubbing the cells, and laying cement on the walls and the floor,” he adds.

The first project they were set on, Philip says, was repairing a section of the prison known as “the barracks”. This would later house members of the Azov Regiment and was where Oleksiy, Vitaliy and Philip would talk to John Harding.

The “barracks” are five two-floored structures on the western flank of the prison, each of which has a small, caged exercise yard and can hold several hundred people.

They were reserved for PoWs, but civilians who worked on them were permitted to stay there as conditions were mildly better than the cells in DIZO or in a neighbouring maximum-security two-storey building called “UUK”, where they had been intermittently held.

Oleksiy says moving to the barracks weeks into his detention was the first time he saw the sky. As an IT professional, he was singled out for specific work. One month into his detention, he was called in to help the prison’s administrative staff deal with a computer virus in the system, where he learned how cash-strapped the jail was.

He managed to strike a deal with guards in which he secured the purchase of a printer and a laptop in exchange for a single phone call to relatives.

“It was mid-April. The only number I remembered off by heart was my ex-wife’s: it would be the first time my family knew for sure I was alive,” he says.

Vitaliy’s 39-year-old wife Tetiana, meanwhile, says she received the last text message from her husband on 24 March as he drove towards Mariupol. It was not until 30 April that a woman recently released from Olenivka called her out of the blue.

“She said my husband’s ‘filtration’ detention term had been prolonged for two weeks, and hoped he would soon be released. But that turned out not to be true,” Tetiana says from Poland where she now lives. “But at least I knew he was alive.”

‘It’s hard to explain how terrible I feel, we don’t know what to do’

The first question the former detainees asked after the attack was: why on earth were inmates in that section of Olenivka? All of the men, who watched videos posted on Russian and Ukrainian Telegram channels of the explosion’s aftermath, say that it was an empty industrial area north of the prison cells, where no one lived. This is consistent with The Independent’s own examination of videos posted online and of satellite imagery.

“They made prisoners work in this area, but no one slept there, it wasn’t kitted out like that,” Arkady says. Oleksiy also says that it wasn’t set up for living. “I think the Russians specifically transferred them to this part to kill them there,” adds Oleksiy.

Ukrainian intelligence, military and security officials claim the site of the blast was fitted out to house prisoners only two days before the attack. After that, detainees from Azovstal were hastily moved in – a point they say is evidence that this was a staged, deliberate attack.

It is impossible to verify that claim, but experts have questioned the narrative of a Ukrainian rocket attack being responsible for the mass killing.

Six specialists who examined available images told The Washington Post that the impact appeared inconsistent with an attack launched by a high-mobility artillery rocket system, because of the lack of shrapnel marks or craters and the minimal damage to internal walls.

They also said that visible signs of an intense fire were at odds with damage caused by the most common HIMARS warhead.

Open-source intelligence analysts, including Bellingcat’s Eliot Higgins and independent Danish analyst Oliver Alexander, have also raised concerns about ground disturbances that appear on satellite imagery around 10 days before the explosion. Alexander said they could be pre-dug graves.

These disturbances to the earth are located in an area the inmates call “the garden”, just south of the main part of the prison. They appear to be opened just before the explosion, then covered up a day after the attack.

The former detainees confirmed to The Independent that the garden had been empty, except for rubbish dumps, from when they were incarcerated until 4 July, though this could not be verified.

Families of Azovstal detainees inside Olenivka are desperately searching for information and have held demonstrations in Lviv demanding intervention from the UN and the ICRC. They worry that, even if their relatives survived the blast, if this was a staged false flag attack it might happen again.

“It’s hard to explain how terrible I feel. We don’t know what to do, we don’t have any information, we don’t know who to call,” says Karina, whose brother is a 31-year-old military medic who was posted to Azovstal during the last stand.

She asked for his identity to be withheld, fearing the worst: his name has not appeared on the list of the dead, but she worries he could be next. She found out her brother was in Olenivka in June, and he later appeared for a split second in a video, posted to Russian Telegram groups, taken by a Russian media outlet that appeared to have been given a tour of the barracks.

The Independent was able to give her more news about her brother as he had briefly met and talked to Vitaliy and Oleksiy in jail. They also confirmed that the location of the video appeared to be in the barracks.

The last time she spoke to him was a few weeks before 29 July, in a short phone call, possibly organised by the Red Cross.

“He was speaking quietly, like someone nearby was trying to listen in. He kept saying the prison is full of people, like pregnant women, injured people and medical staff from Mariupol,” Karina says.

“He kept asking, ‘How is it okay in the 21st century for pregnant civilians, for medics to be treated like prisoners of war in jail?’”

‘I am all alone in the world’

For the families of the Olenivka detainees, their loved ones one day just left and vanished.

On 30 March, Ludmilla’s son Dima sent her a single-line text message asking her to pray for him and his girlfriend as they approached Mariupol, from where he hoped to rescue their grandparents.

The 54-year-old told him she loved him and that he was “the most precious thing” to her. He replied that he was sure everything would be OK, and that if they were stopped at a checkpoint they would not try to continue to Mariupol.

But he never messaged again. His phone never switched back on. To this day, she has not heard a single word from him.

Like so many parents, Ludmilla has spent the past few months frantically trying to work out if her only child is still alive.

“For two weeks I didn’t know anything. Then I got a phone call from a person I didn’t know, telling me that they were all stopped in Mangush [outside Mariupol] and they were held captive in the town of Dokuchaevsk.”

The unknown caller had apparently been freed, but was too frightened to say more and hung up. Later, Dima’s girlfriend was released with more information: that they had been taken to the city of Donetsk for 10 days.

“It is very difficult to get any information. That is why the relatives who have captured children get together and swap information online. It’s through this that I understand he had been taken to Olenivka,” Ludmilla says.

Unlike Vitaliy, Oleksiy, Philip and Arkady, Dima has never been released; he has never reappeared. So far, none of his cellmates have been freed to bring further news. Ludmilla assumes Dima remains behind bars in Olenivka, but no one knows what state he is in.

“We understand he, and other people with him, were accused of terrorism and were notified they were going to be sentenced for 20 years in prison,” she says. “We don’t know what that means and I am so frightened.”

Her testimony highlights that Oleksiy, Philip, Vitaliy and Arkady are among the lucky few. The four detainees were among around 20 who were suddenly freed on 4 and 5 July.

“I don’t know why I was released,” Arkady says. “They said, after 100 days of being there, ‘You are not terrorists and you are free.’”

There are hundreds if not thousands of detainees still left behind, many of whom may still have had no contact with relatives.

Yuri Belousov, a Ukrainian prosecutor who is investigating alleged war crimes committed against Ukrainians, says there have been at least 12,500 cases of missing people reported to the national police hotline. “The true number is much higher because not everyone files a case, so they won’t be logged in the database.”

Philip says civilians in Olenivka who were ex-military or worked in the police force were particularly worried about never making it out.

“We made a group in prison that supported each other, but there were people who isolated themselves, sunk into a deep depression,” he says. “One former border guard I know had a total breakdown, and kept repeating over and over again, ‘I will spend 25 years in here. My life is over. My life is over.’”

Oleksiy and Vitaliy say they are still dealing with the physical and emotional scars of their time behind bars.

One former border guard had a total breakdown and kept repeating, ‘I will spend 25 years in here. My life is over’

Oleksiy says his teeth are damaged from beatings, poor medical treatment and bad food. “I also have problems with my blood pressure. It’s hard to move long distances,” he adds.

Vitaliy, meanwhile, says he suffers from punishing headaches, and using phones and computers for long periods of time is difficult. “We are very tired all the time,” he adds.

But part of the healing process is in a determination to keep volunteering. “Before I was taken, I was a coordinator at a reception centre welcoming refugees from Mariupol. I still want to do this,” says Oleksiy, speaking from Poland, where he is now recovering. “This would be one way to put my experience, what I went through, to good use.”

Meanwhile the families still waiting for news are stuck in a kind of hell – scrolling through social media for any glimpse of their missing loved ones.

“I am all alone in the world and I don’t know what to do,” says Ludmilla, crumbling into tears. She now lives alone in a quiet cabin north of Kyiv. All day, every day she scours social media for any word of her son.

“One day my only child left to rescue his grandmother and never came back. Please help me find my son.”

Names have been changed to protect identities

Coming soon to Independent TV – On The Ground | The Missing: The Ukrainians abducted in Putin’s war

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments