Why Russia’s attempts to get round oil sanctions risk ecological disaster

Russia is taking increasingly drastic and hazardous measures in order to maintain its oil trade amid sanctions over the Ukraine war, bringing a much greater risk of a spill. Shweta Sharma reports

The last time Russia was involved in a major oil spill in the Arctic, it triggered one of the worst manmade environmental disasters in recent history. The collapse of a storage tank near Norilsk, due to melting permafrost, spilled some 21,000 tonnes of oil into the vulnerable Arctic ecosystem, contaminating a 350 sq km area and turning the bright turqoise waters of Siberia’s Ambarnaya River into red sludge.

Three years later, the waters of the Ambarnaya are still red, and the consequences of the incident are expected to last for decades. State investigators have accused the company involved of negligence and mismanagement, and Vladimir Putin was said to be personally angered by alleged delays in informing the authorities about the spill.

Now, experts and environmentalists fear that the way Russia is responding to Western oil sanctions over the Ukraine war is creating the perfect set of circumstances for another major spill, and that another disaster is overdue.

Before the war, the European market accounted for at least 32 per cent (139 million metric tonnes of crude and 76 million metric tonnes of refined products) of Russia’s oil exports in a year, largely through well-established pipelines or relatively short sea routes. Now, sanctions mean most European countries have stopped imports of Russian oil altogether, and a price cap applies to the use of West-based companies to insure and transport oil exports to third countries.

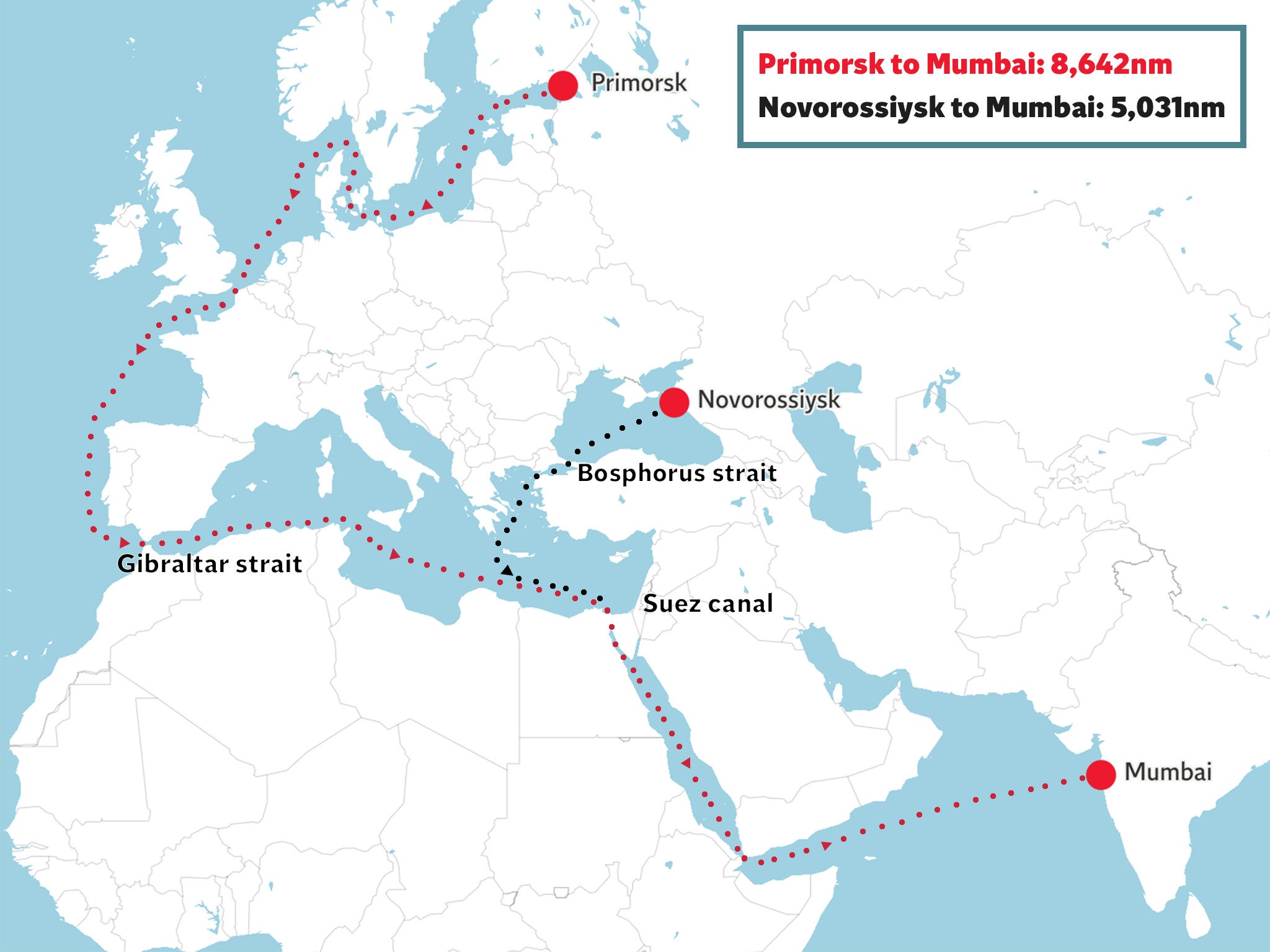

As previously reported by The Independent, Russia has maintained oil exports at a similar rate to pre-war levels by pivoting sales to India and China, albeit at significantly reduced prices. To do so, it is forced to deliver its crude oil using much longer sea routes, engaging in risky sea-to-sea transfers and deploying a so-called “shadow fleet” of ageing and unaccountable vessels.

Every month, now, more than 150 tankers laden with Russian oil are passing out of the Baltic Sea, a shallow body of water that is covered with ice for part of the year, and through the crowded, narrow channels of the Danish straits, according to industry observers.

“I think the world is very close to seeing an environmental disaster somewhere on this long route of Russian cargo coming to Asia,” Bruno Macaes, an author on international geopolitics and a former Portuguese secretary of state for European affairs, tells The Independent. “It is almost inevitable,” says Macaes, who is researching Russia’s oil industry and the impact of Western sanctions for his next book.

Ship-to-ship (STS) transfers in the open ocean are notoriously risky, involving smaller cargo vessels carrying Russian oil through the narrow straits of northern Europe and transferring it to larger ships.

At least 31 STS transfers have taken place so far in 2023, up dramatically from 24 in the whole of last year and just six in 2021, before Putin invaded Ukraine, according to data from Kpler, a global trade analytics platform.

“Historically, ship-to-ship transfers were not needed, as most of Russia’s exports were to Europe on shorter voyages, but increasing hand-offs in the middle of the sea raises the risk of an accident,” says Matthew Wright, senior freight analyst at Kpler.

“It comes down to the fact that they’re older vessels mainly, and that maintenance and crewing may not be good enough.”

He adds: “The reason Russian exports sometimes require STS is because Russian ports can’t accommodate the largest vessels.”

The route to reach India and China is not only lengthy but passes through some of the busiest shipping lanes in the world. Tankers must go through the English Channel and then enter the Mediterranean via Gibraltar, before traversing the narrow, manmade channels of the Suez Canal and emerging into the Arabian Sea, according to the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air.

Western-led sanctions were designed not to stop Russia from selling oil altogether – such an effort, if successful, would have seen the cost of living for US and European consumers rocket. Instead, they aim to throttle Moscow’s income, restricting the amount of money the Kremlin has available to fund its war in Ukraine. The main tool for this is an EU and G7 price cap, which means many of the world’s largest logistics companies and insurers can only support Russian crude oil exports if they meet a maximum price of $60 (£47) per barrel.

An unintended consequence of these sanctions has been a move by traders to continue their business in the shadows, with an opaque and more ecologically dangerous “grey” or “shadow” fleet plying these long trade routes.

The shadow fleet consists of vessels sold by companies based in Europe to owners who were not previously active in the tanker market, mainly headquartered in Hong Kong. The same tankers then continue to transport Russian crude, but without the support network of experienced operators, insurers and inspectors.

“If market prices for oil rise above the price cap, Russia [now] has access to some ships that don’t rely on EU and G7 services – the so-called ‘shadow fleet’,” says Craig Kennedy, an expert on Russian oil at Harvard’s Davis Center.

Kpler data indicates that Russia is currently relying on the shadow fleet for around 20 per cent of oil exports, and experts predict that this figure will rise if the conflict, along with Western sanctions, continues.

“If Russia continues to increase its use of shadow tankers to circumvent sanctions, it might also be increasing the risks of a catastrophic spill in the Baltic,” says Kennedy. “These ships are on average very old. Many have mixed inspection records and may not be properly equipped for operating in icy conditions,” he tells The Independent.

Besides the increased risk associated with ageing vessels, experts are concerned that an oil spill involving the shadow fleet would create a situation in which no one could be held accountable for a clean-up costing potentially billions of dollars.

“[These vessels] are insured with little-known, niche insurers with low levels of transparency,” says Kennedy. “So, if there’s a spill, it’s hard to know whether their insurers will have enough capital to cover the clean-up costs, since disclosure of their financing is hard to come by.”

According to S&P Global, a Manhattan-based market intelligence company, an estimated 443 vessels with a deadweight tonnage over 10,000 are currently operating within the Russian shadow fleet. This is of a total of approximately 1,900 vessels, regardless of nationality or ownership, that pose a higher potential risk in relation to Russian sanctions, being involved in activities such as Russian port calls and ship-to-ship transfers.

An S&P Global report said that this number is only growing, with 35 vessels introduced on Russian tanker routes in just three months up to mid-February. Around two-thirds of these vessels are more than 13 years old, and they are undertaking direct voyages to offload cargo in countries such as Egypt, Nigeria, China and India, the research shows.

Wright says that, although it is difficult to ascertain whether these ships are insured or not, there is a greater potential risk from the use of older vessels where their cover is uncertain.

“Some of these ships are now managed by owners who have a limited track record of ship ownership. It is therefore unclear how well the ships will be maintained and crewed. With question marks over the insurance cover, if there were an accident, salvage operations could be delayed,” he adds.

Macaes says there is a particular onus on India to consider the risks involved in its purchases from Russia, as these imports are entirely seaborne – China is able to import much of its crude from Russia through pipelines.

“It is for India to look into it very carefully [and] at what it will do when they have an environmental accident, as such an ecological disaster will have political as well as environmental consequences,” he says.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments