Russian spy agency GRU appears to reveal details of operatives' children in latest blunder

Spy agencies reportedly turned children into centurions in crude attempt to disguise their identity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For a country with an average life expectancy barely above 70, the existence of a hundred centurions living in two hostels in northwest Moscow appeared suspicious.

So suspicious, says a new report, the Russian pension fund ordered an investigation. Dead souls, after all, have long been a profitable business for local criminals and novelists.

The report, published on Friday by a publication funded by Kremlin foe Mikhail Khodorkovsky, says the pension fund investigation was shut down on the orders of the Russian Ministry of Defence. What the probe had inadvertently revealed, it claimed, were the names and personal details of the children of military intelligence agents.

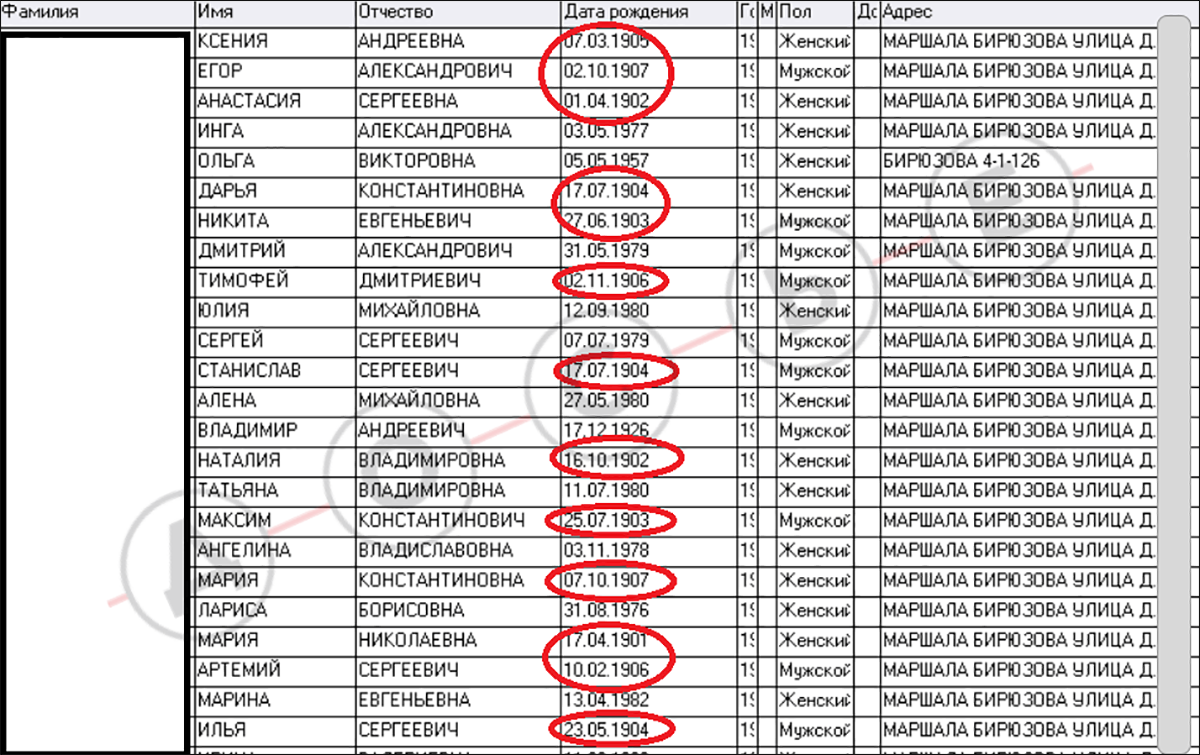

Their identities had apparently been crudely concealed, in 2011, by taking 100 years off their date of birth: those born in 2005 were switched to 1905, and so on.

Veteran investigative journalist Sergei Kanev, says he replicated the findings of the pension probe using readily-available databases.

He ran searches for addresses with known connections to Russian military intelligence in phone directories. These revealed 47 “centurions” in one hostel on Volokolamsky Road, in northwest Moscow, and another 56 in a hostel nearby, on Marshal Biryusova Street.

The latter address famously housed Anatoly Chepiga – aka Ruslan Boshirov, one of two men accused of conducting a nerve agent attack in Salisbury – when he studied in Moscow.

It has become widely known as the “old people’s home” among agents, the journalist claims, though he quotes only a single security agency source.

Another easily-obtainable dataset, from the police – one of the most corruptible institutions in Russia – led the investigator to his second set of discoveries.

GRU agents had, it appeared, fallen victim to a robbery involving $90,000 in cash. Another officer reported his car stolen. But the victims had also been on the wrong side of the law, assaulting police officers and shooting people with rubber-bullet handguns.

The revelations chronicle the latest in a series of humiliating blunders by Russia’s military intelligence agency.

Not for the first time, it appeared the bureaucratic oversights of senior officers had allowed investigators to unlock embarrassing operational details.

Previous investigations pounced on decisions to issue agents passports in numerical sequence; to send operatives to spy on European agencies while using their real identities; and to tie passports and driving licences to known GRU addresses.

Those arbitrary decisions allowed internet researchers – not to mention foreign spy adversaries – to identify hundreds of suspected agents in domino fashion.

It has led to the most difficult period in the military intelligence agency’s recent history.

In the first decade of Putin’s rule, the GRU was sidelined by flashier colleagues in the Federal Security Service and Foreign Intelligence Service. But starting from around 2014, the organisation moved beyond its usual zone of influence, and began to play important roles in military interventions in Ukraine and Syria.

That past performance makes it unlikely the gaffe-stricken agency will fall out of favour with the Kremlin any time soon.

The Kremlin has not responded to the latest report, and previously indicated it would only issue statements in reply to “official, published data”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments