Refugee crisis: The Nazi-era airport that's now 'home' to 3,000 refugees

Tempelhof was built as the first cornerstone to Germania - the mythical city Hitler envisioned as the centrepiece of the Nazi empire

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I wait for Nabeel, a young Iraqi who has promised to show me around his new 'home' at Tempelhof, the historic Berlin airport that now houses 3,000 refugees.

I am standing by the Luftbrückendenkmal - the large pronged memorial to the Berlin airlift which kept Berliners alive during the blockade of 1948 and 1949. As I wait, two men pass me shivering in clothes too thin for the German winter, speaking Arabic, smoking.

One of them smashes out his cigarette and goes over to the memorial. Taking off his shoes and using his coat as a makeshift prayer mat, he performs the Salah on the platform in front of it.

The symbolism of this act is not lost on me.

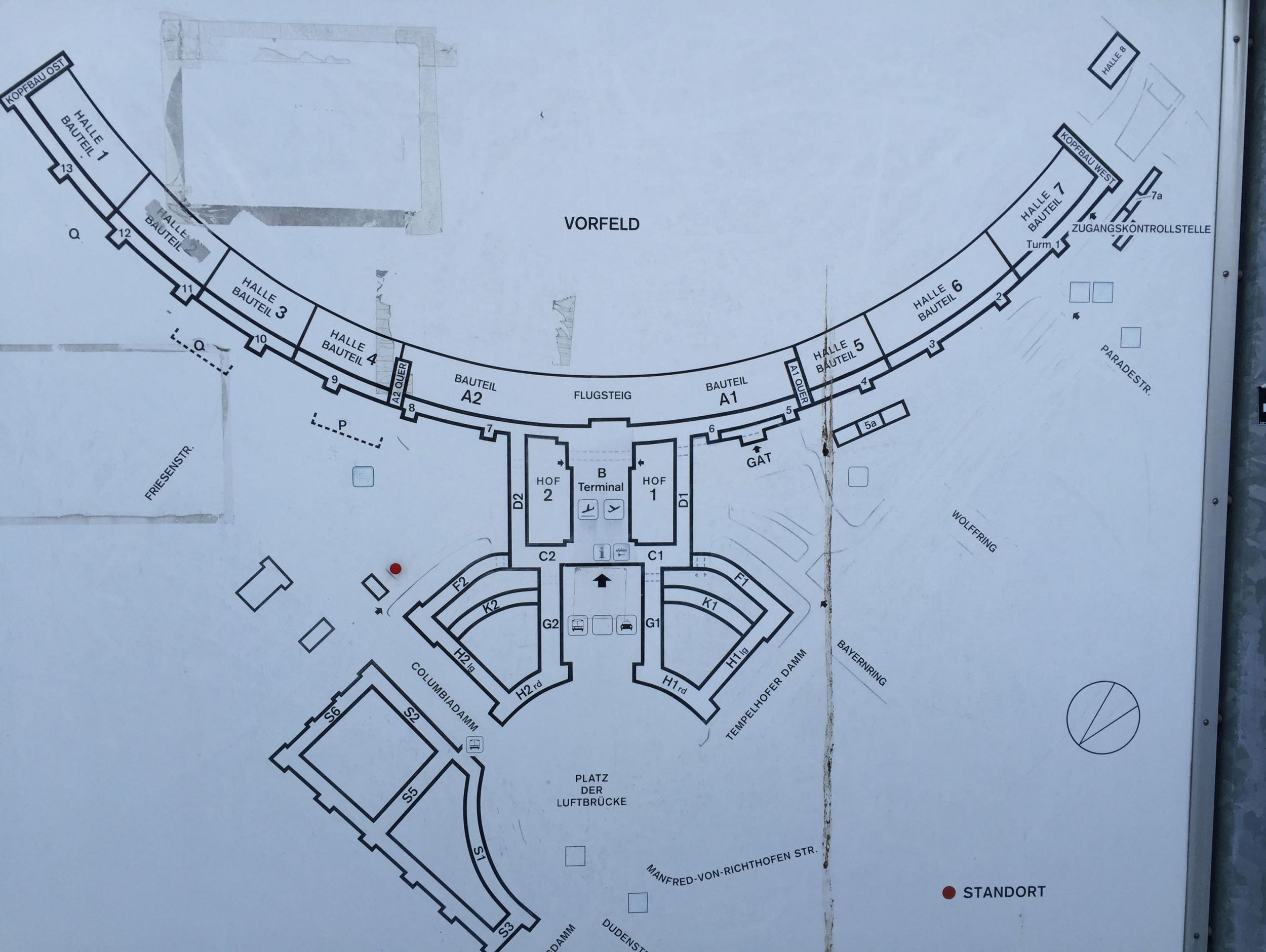

He is praying at a statue that memorialises the moment when West Berlin was rescued from the repressions of Stalin’s Russia, outside Tempelhof, an airport built as the first cornerstone to Albert Speer’s Germania - the mythical city that Hitler and his allies envisioned as the centrepiece of their Nazi empire.

The airport building itself, once described by Norman Foster as the ‘mother of all modern airports’, a quarter of a kilometre in length, has been empty since its closure in 2008.

Its new occupants have journeyed from all over the Middle East – Afghans, Syrians, Iraqis and Lybians, as well as a smattering of people from the Ukraine and Moldova, in the biggest wave of mass migration to Germany since the Second World War.

Conditions inside the airport are not good.

Partly because the building has been abandoned for so long, there isn’t any infrastructure - no showers, no kitchens, not enough toilets – and partly because due to the pressure of so many crammed together from different nations and ethnic groups there are simmering tensions which often erupt into violence, most recently a mass brawl at the end of November.

Nabeel is 21, shy and softly spoken with English he has taught himself. He’s exhausted, partly because the noise in Hangar 4, where he is housed, keeps him awake at night - "so many children!". He is also carrying an injury which is his reason for leaving Baghdad and which still gives him pain.

The little finger on his right hand is missing, just a raw stub, newly healed, but a livid wound. In September, he was abducted by a criminal gang who kept him blindfolded and locked up while they demanded ransom money from his parents.

"I thought I would die," he tells me. "I didn’t know what they really wanted."

As a signal of their intent they cut off his finger and sent it to his parents. After four days he escaped. Three days later he got on a plane to Turkey, his hand wrapped in a bandage, and he hasn’t looked back.

"I didn’t even tell my mother where I was going. But I couldn’t stay. I don’t know what will happen to me in Baghdad."

When he speaks about this his eyes glitter, he is still quite evidently, utterly terrified.

He left Iraq at the beginning of October and arrived in Germany 19 days later after a tortuous and sometimes dangerous overland journey.

He crossed from Turkey to Greece in a boat from Izmir which cost him all his life savings, then through the Balkans and Hungary and into Germany where he was moved around between Passau - a border town in the East - and Dusseldorf, before finally arriving in Berlin.

Here he is, waiting, as all the refugees must, to be processed: a long and sometimes tortuous process of validation and registration.

Meanwhile, he attends compulsory German classes which are intended to prepare him for life in Germany. But living in Tempelhof is tiring and fractious.

They are watched over by Arab guards, who, he complains are "worse than the German guards," for reasons I can’t quite get him to articulate. "The Syrians hate the Afghans," is all he says.

He sleeps on a bunk bed sharing a makeshift partitioned space in the hangar with 12 others. There are now more portaloos and there are buses to take them to showers in the local sports centres every morning. But it’s noisy and there is no privacy. He hangs around a lot, avoiding trouble and doing his German homework.

They have all been warned, too, to stay indoors over the New Year's celebrations where the fireworks turn Berlin into an imitation war zone.

I ask him if he ever thinks he will return to Iraq and he shrugs. Apart from the threat of Isis, Iraq has been in the grip of a vicious and protracted civil war that has pitted Shia against Sunni, and in the vacuum created by inadequate governance, gangsterism is rife.

"Life with Saddam was peaceful, we were free," he says. There is a strange frisson in knowing that the West's misadventures in the Middle East have brought me to this encounter in Berlin, so much so I feel compelled to tell him that the war did not happen in my name.

When we part, I tell him about the man praying at the foot of the statue to the Berlin airlift and he laughs.

"God is good," he says. "He looks after all of us." Then he looks sad. "It doesn’t matter where you are from. Inside of each of us, our blood is the same colour red."

The Germans, perhaps more than any other European nation have cause to remember this truth.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments