Now Schindler's ark looks for its own saviour: Czech town pins its hopes on restoration of the ruined factory immortalised in the Oscar-winning film

The Czech-German industrialist sheltered 1,200 Jewish labourers from the Holocaust in his Brnenec factory for seven months until they were liberated in 1945

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The windows in the red-brick buildings are smashed, the walls are damp-ridden and most of the doors have been torn off. The Czech factory where the Second World War hero Oskar Schindler helped 1,200 Jews escape the Nazi Holocaust looks as if it has been forgotten since 1945.

However, residents in the eastern Czech town of Brnenec, where the former factory is located, are planning to put the building on the market. They want the complex to be either used once again for manufacturing or turned into a Holocaust museum recalling Schindler's feat for posterity.

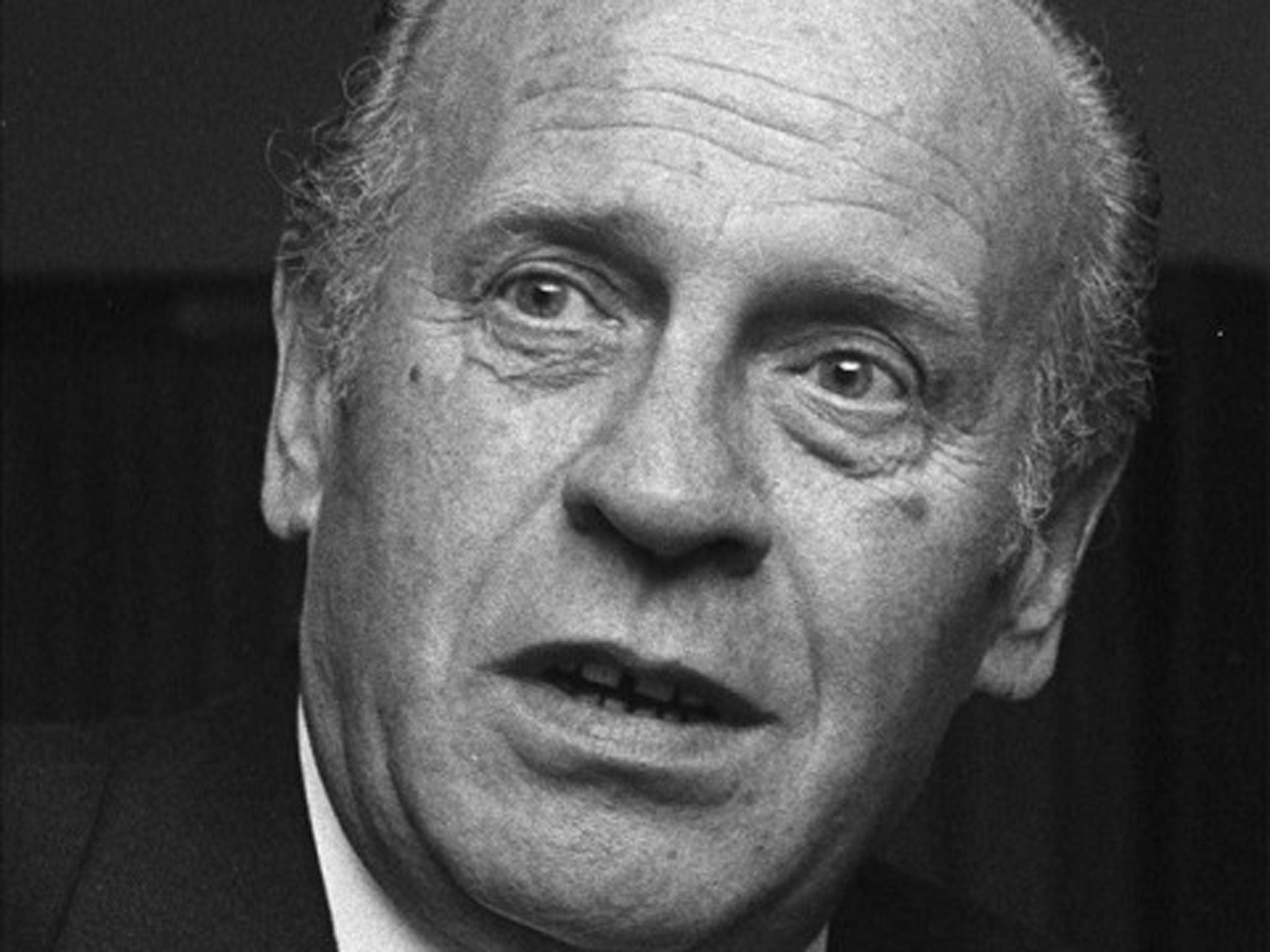

Schindler, a Czech-German industrialist, sheltered 1,200 Jewish labourers from the Holocaust in his Brnenec factory for seven months until they were liberated in 1945. The story featured in Steven Spielberg's 1993 film Schindler's List. Spielberg visited the factory, but the film was made elsewhere.

Brnenec's mayor, Blahoslav Kaspar, insists that Schindler's former complex has "great potential", now that the legal disputes surrounding it are close to being resolved. He says that the town would be prepared to offer the factory site for a nominal sum to an investor with the resources to develop the complex.

The idea of turning the site into a Holocaust memorial has been welcomed by the Federation of Jewish Communities in the Czech Republic. "It is a great idea," Thomas Kraus, director of the organisation, said. "The museum should have been opened when the Schindler film was released. This is our last chance."

Mr Kraus said that the Czech Republic's former communist regime had largely ignored the country's Jewish heritage. "Few Czechs knew who Schindler was until the film came out. We are running out of Holocaust survivors; material memorials, such as his factory, are the only things left to bear testimony," he added.

Schindler ran an enamelware factory in the Polish city of Krakow during the Second World War. As the Soviet Red Army advanced towards Poland in 1944 he relocated its Jewish workforce to Brnenec, 120 miles east of Prague. The industrialist helped many of his workers to escape being sent to their deaths in Auschwitz by bribing his Nazi overseers and telling them that his workers were vital skilled labourers.

After 1945, wanted as a war criminal because of his Nazi party membership, Schindler fled to West Germany and then South America, where he ran a string of unsuccessful businesses. Returning to West Germany in the late 1950s, impoverished and unrecognised, he was supported by the Jews he had helped. He died in 1974, aged 66. His Brnenec factory was nationalised by Czechoslovakia's communist regime in 1948. It was privatised after 1989 and went bankrupt in 2004.

Schindler's decaying factory still contains the house that he lived in, but most of the complex faces imminent ruin. The roofs are leaking and much of the compound is polluted with discarded textile dyes and poisons. The town's mayor estimates that the clean-up could cost up to €1.5m (£1.2m).

"It is a tragedy for the town and the whole region," Mr Kaspar told Businessweek magazine. "It has become a huge burden for us. We need an investor to clean it up and create jobs for local people."