Panama Papers: Millions of leaked documents expose how world’s rich and powerful hid money

More than 11 million documents accuse former and current heads of state of tax evasion, avoiding sanctions and money laundering

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Millions of confidential documents have been leaked from one of the world’s most secretive law firms, exposing how the rich and powerful have hidden their money.

Dictators and other heads of state have been accused of laundering money, avoiding sanctions and evading tax, according to the unprecedented cache of papers that show the inner workings of the law firm Mossack Fonseca, which is based in Panama.

The documents, dubbed "The Panama Papers", reveal links to 72 current or former heads of state and accuse some of them of having vested interests in their own banks and looting their own countries.

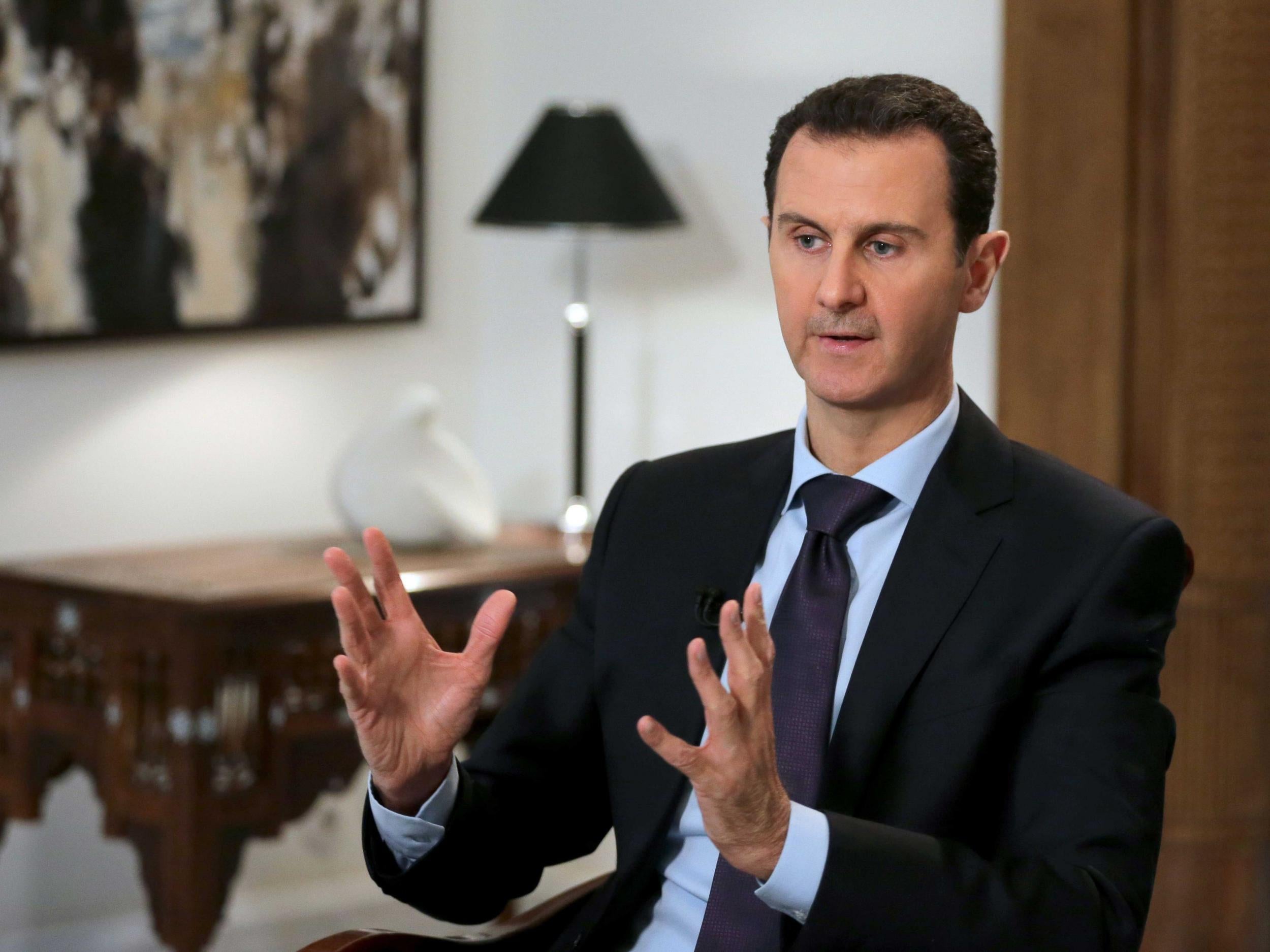

The data shows links to families and associates of some of the most powerful people in the world, including the former president of Egypt, Hosni Mubarak, the former Libyan leader, Muammar Gaddafi and the current president of Syria, Bashar al-Assad.

In the UK, several elected officials are involved with the law firm, including Baroness Pamela Sharples and the MP Michael Mates. They provided responses to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and have either denied any financial benefit to the offshore companies or have completely denied the allegations of working with the law firm.

Two close allies of the Russian President, Vladimir Putin, are linked to an alleged money-laundering ring thought to be worth $1billion, run by a bank based in St Petersburg, Bank Rossiya. One of those is the concert cellist Sergei Roldugin, who has known Mr Putin for many years, is godfather to Mr Putin’s daughter Maria, and introduced him to his now ex-wife Lyudmila. The bank in question has already faced sanctions from the European Union and the US after Russia's invasion of Crimea in 2014.

The papers were initially leaked via the German newspaperSüddeutsche Zeitung to the ICIJ. Gerard Ryle, director of the ICIJ, who has been analysing the documents along with 107 media outlets across more than 70 countries, told the BBC: “I think the leak will prove to be probably the biggest blow the offshore world has ever taken because of the extent of the documents.” The leak will be the subject of a Panoramadocumentary tonight. The source of the leak remains unidentified.

Another accusation in the files is that the prime minister of Iceland, Sigmundur Gunnlaugsson, had an undeclared interest in the bailed-out banks in the country, hiding millions of dollars in Iceland’s banks via an opaque offshore company.

Iceland was one of the few countries following the 2008 financial crisis to jail several of its bankers, who were accused of taking excessive risk which led to the collapse of their economy.

Yet Mr Gunnlaugsson and his wife bought Wintris, an offshore company, in 2007 but did not declare an interest in the company when they entered parliament. The company was used to invest millions of inherited money. He then sold his 50 per cent stake in Wintris to his wife for 70 pence ($1) eight months later.

Mr Gunnlaugsson has faced calls for his resignation but has reportedly said he has done nothing illegal and his wife has not benefitted financially from the arrangement.

Offshore companies are often located in countries such as Panama and are subject to their own tax rules, often functioning as tax loopholes or requiring much lower taxes than in an investor’s home country.

The law firm documents additionally show how individuals could take out large amounts of cash without revealing who they are to the public. In one case, the firm acted on behalf of a man who pretended to be the owner of $1.8m so that the real owner could take out the money without revealing their identity.

The ICIJ has listed 140 politicians from more than 50 countries who are linked to offshore companies in 21 tax havens, including countries such as Argentina, Georgia, Iraq, Jordan, Qatar and Ukraine.

Mossack Fonseca said it has operated “beyond reproach” for 40 years and has never been acused or charged with criminal wrong-doing.

“If we detect suspicious activity or misconduct, we are quick to report it to the authorities,” it said in a statement. “Similarly, when authorities approach us with evidence of possible misconduct, we always cooperate fully with them.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments