'Mein Kampf' reissued: Is Adolf Hitler's book too dangerous for the general public?

The 1923 Nazi manifesto has been banned from Germany since World War II

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

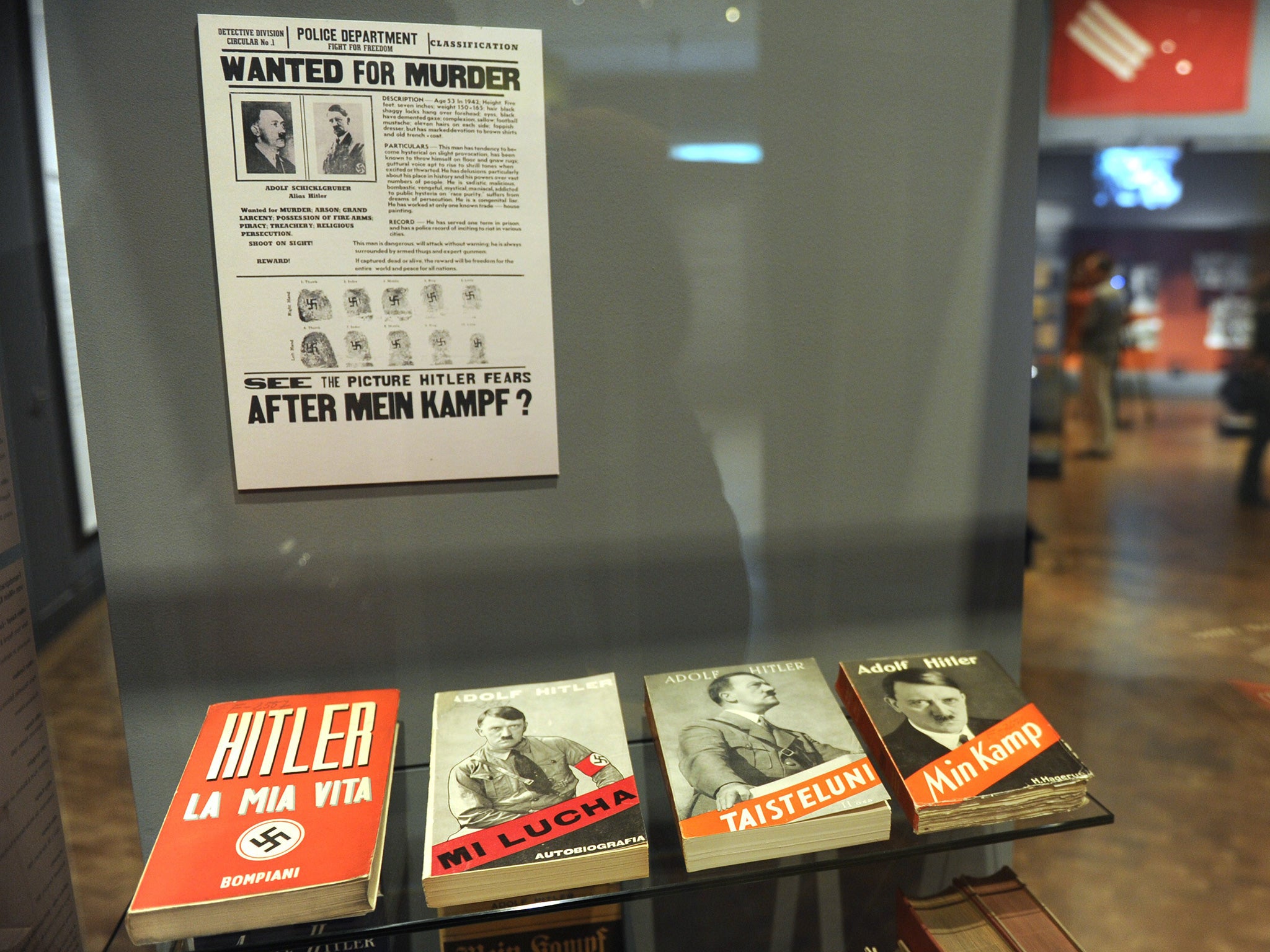

Old copies of the offending tome are kept in a secure “poison cabinet,” a literary danger zone in the dark recesses of the vast Bavarian State Library. A team of experts vets every request to see one, keeping the toxic text away from the prying eyes of the idly curious or those who might seek to exalt it.

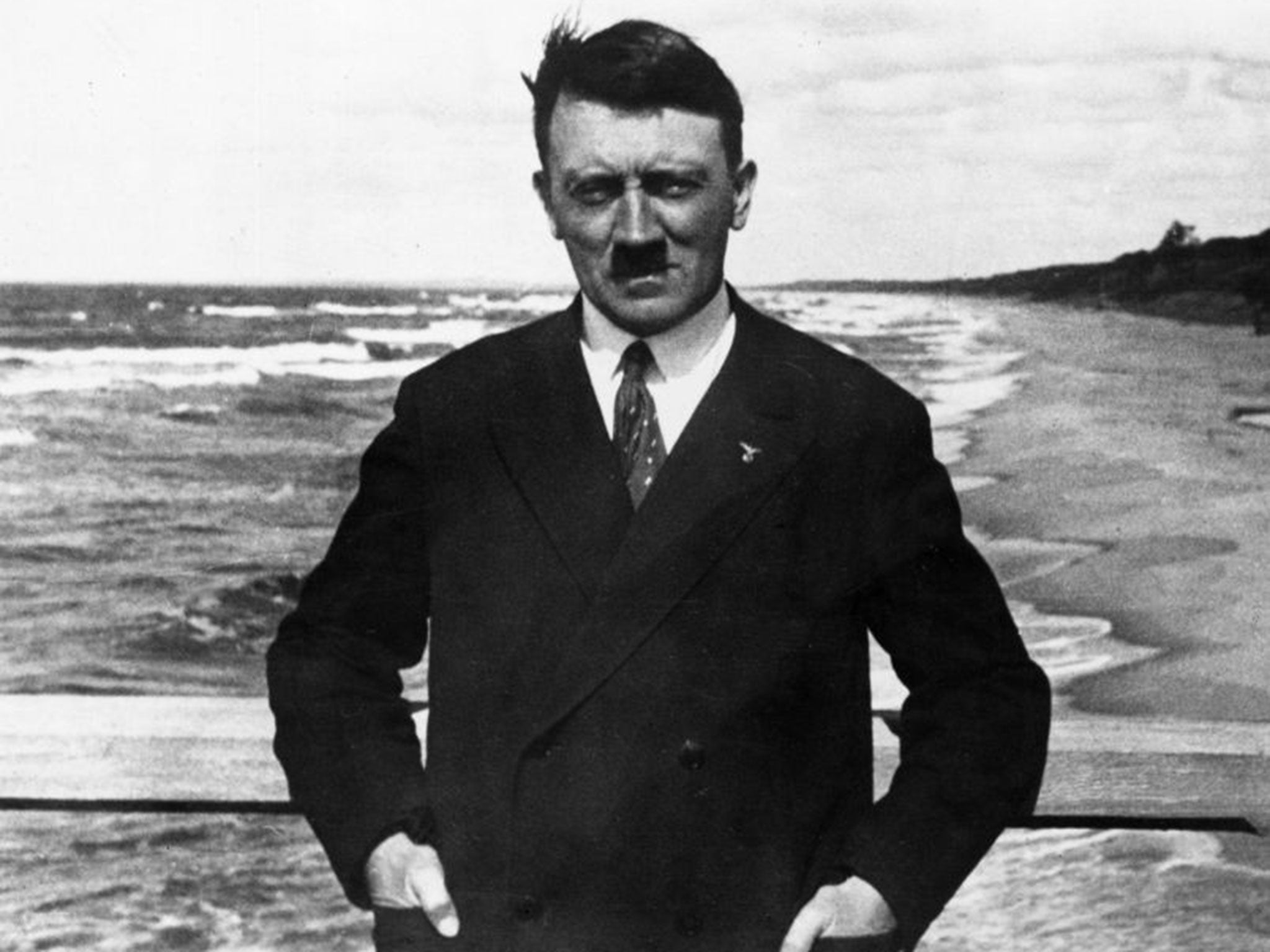

“This book is too dangerous for the general public,” library historian Florian Sepp warned as he carefully laid a first edition of “Mein Kampf” — Adolf Hitler’s autobiographical manifesto of hate — on a table in a restricted reading room.

Nevertheless, the book that once served as a kind of Nazi bible, banned from domestic reprints since the end of World War II, will soon be returning to German bookstores from the Alps to the Baltic Sea.

The prohibition on reissue for years was upheld by the state of Bavaria, which owns the German copyright and legally blocked attempts to duplicate it. But those rights expire in December, and the first new print run here since Hitler’s death is due out early next year. The new edition is a heavily annotated volume in its original German that is stirring an impassioned debate over history, anti-Semitism and the latent power of the written word.

The book’s reissue, to the chagrin of critics, is effectively being financed by German taxpayers, who fund the historical society that is producing and publishing the new edition. Rather than a how-to guidebook for the aspiring fascist, the new reprint, the group said this month, will instead be a vital academic tool, a 2,000-page volume packed with more criticisms and analysis than the original text.

Still, opponents are aghast, in part because the book is coming out at a time of rising anti-Semitism in Europe and as the English and other foreign-language versions of “Mein Kampf” — unhindered by the German copyrights — are in the midst of a global renaissance.

Although authorities here struck deals with online sellers such as Amazon.com to prohibit sales in Germany, new copies of “Mein Kampf” have become widely available via the Internet around the globe. In retail stores in India, it is enjoying strong popularity as a self-help book for Hindu nationalists. A comic-book edition was issued in Japan. A new generation of aficionados is also rising among the surging ranks of the far right in Europe. The neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party in Greece, for instance, has stocked “Mein Kampf” at its bookstore in Athens.

Regardless of the academic context provided by the new volume, critics say the new German edition will ultimately allow Hitler’s voice to rise from beyond the grave.

“I am absolutely against the publication of ‘Mein Kampf,’ even with annotations. Can you annotate the Devil? Can you annotate a person like Hitler?” said Levi Salomon, spokesman for the Berlin-based Jewish Forum for Democracy and Against Anti-Semitism. “This book is outside of human logic.”

Not surprisingly, the new edition has become a political hot potato, illustrating the always-awkward question of how modern Germany should deal with its past. Initially, Bavaria, for instance, had pledged $575,000 to directly support publication of the new edition for historical purposes. But it backed out after the Bavarian governor’s 2012 visit to Israel, where he heard withering criticism of the proposal from Holocaust survivors.

That left the state-funded organization putting out the new edition — the Munich-based Institute of Contemporary History — in a bind. Since the late 1940s, the institute has analyzed the rise and aftermath of the Nazi era, putting out annotated texts such as Hitler’s speeches. The single most important work it has not yet published in annotated form is, in fact, “Mein Kampf.” Since 2012, it has had a team of academics laboring on the new edition in preparation for the copyright’s expiry.

Despite the chorus of opposition, particularly from Jewish groups and Holocaust survivors, the institute has opted to go ahead with publication, funding it from its general budget — a task made easier by the fact that Bavaria allowed it to keep the original grant for other research purposes.

“I understand some immediately feel uncomfortable when a book that played such a dramatic role is made available again to the public,” said Magnus Brechtken, the institute’s deputy director. “On the other hand, I think that this is also a useful way of communicating historical education and enlightenment — a publication with the appropriate comments, exactly to prevent these traumatic events from ever happening again.”

A rambling, repetitive work panned by literary critics for its pedantic style, “Mein Kampf” was drafted by Hitler in a Bavarian jail after the failed Nazi uprising in Munich in November 1923. It was initially published in two volumes in 1925 and 1926, with later, joint editions forming a kind of Nazi handbook. During the Third Reich, some German cities doled out copies to Aryan newlyweds as wedding gifts.

The book also laid the groundwork for the Holocaust, stating, for instance, that Jews are and “will remain the eternal parasite, a freeloader that, like a malignant bacterium, spreads rapidly whenever a fertile breeding ground is made available to it.”

Contrary to popular belief, “Mein Kampf” — or “My Struggle” — was never banned in postwar Germany; only its reprinting was. Of the more than 12.4 million copies in existence before 1945, hundreds of thousands are thought to survive. Old copies can still be sold in antiquarian bookstores. But public access is generally confined to a few restricted repositories such as the library here in Munich, which only permits viewings based on academic need or historical research. Bavarian authorities also have played cat-and-mouse with those who have sought to publish “Mein Kampf” online, acting to block German-language versions posted on the Internet whenever possible.

Brechtken said the new print version will point out, for instance, how Hitler appeared to borrow his views from other sources, and it will refute his racist claims. Bavarian officials also say they will seek to apply incitement-to-hate laws to any attempt to publish unannotated versions in the future. But so far, they say they will not seek to block publication of the institute’s expanded version, citing the benefits it may bring to historical research.

Yet vocal opposition appears to be growing. Charlotte Knobloch, head of the Jewish community in Munich, said she had not vigorously opposed it when the project first surfaced. But her position, she said, hardened after hearing from outraged Holocaust survivors.

“This book is most evil; it is the worst anti-Semitic pamphlet and a guidebook for the Holocaust,” she said. “It is a Pandora’s box that, once opened again, cannot be closed.”

Stephanie Kirchner in Berlin contributed to this report.

© The Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments