‘We want justice for our loved ones’: How Italy’s government failed to protect Bergamo

Behind the staggering death toll in Italy’s worst-hit region are families whose lives have been ripped apart by Covid-19. Federica Marsi reports from Bergamo

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There is no more chatting in the coffee bars of Bergamo. Streets lie empty, the silence punctured by the sound of blaring ambulance sirens. In the distance, only a swing and a small merry-go-round at a local park move in the breeze. Priests have instructed the church to ring the death knell just once a day, to stop the bells from ringing all day long.

In Italy’s north, ravaged by the world’s deadliest coronavirus outbreak, hand-drawn notes taped at every corner make an attempt at reassurance: “Andrà tutto bene” – everything will be fine.

But the residents of Bergamo – the country’s worst hit city – are experiencing a collective emotional trauma that, bereaved families claim, was hatched out of blunders and corporate interests.

‘Noi Denunceremo’ – we will speak up

Over 30,000 of its residents have so far signed a petition demanding an inquiry in why authorities never declared Bergamo a so-called red zone, and how negligence turned the Pesenti Fenaroli hospital into a hotbed of contagion.

“We want justice for our loved ones,” Stefano Fusco, the founder of a Facebook voicing residents’ demands, tells The Independent. The page “Noi Denunceremo” – “we will speak up” – has reached more than 25,000 followers in the span of a couple of weeks and collected dozens of accounts from families torn apart by the spread of Covid-19.

The hospital that become a threat to life

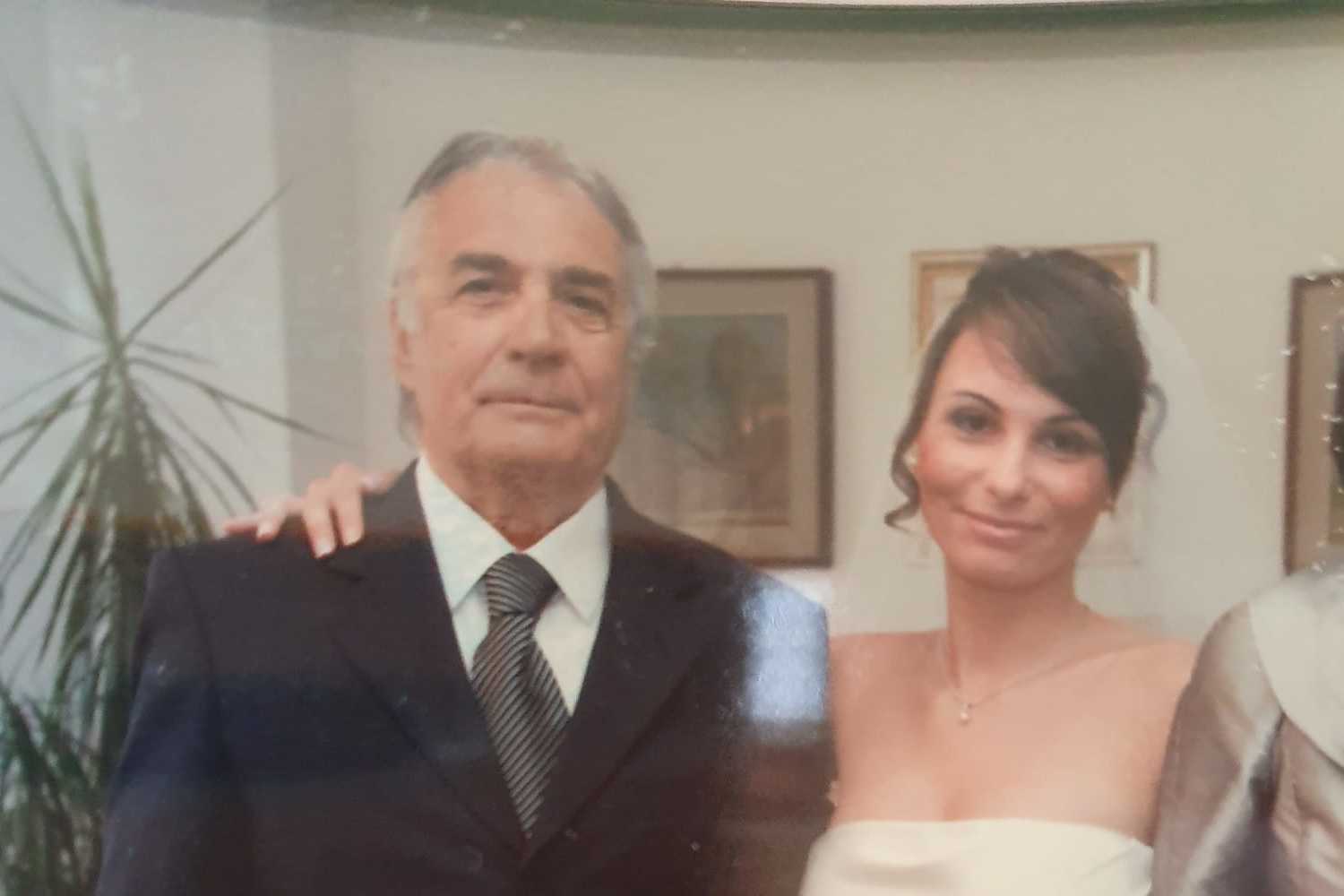

One family looking for answers and comfort online is that of Sara Gargantini, whose father, Giancarlo, passed away at the Bolognini hospital in the town of Seriate in Bergamo on 7 March.

The sturdy 82-year-old grandfather had developed a fever on 20 February, just as Italy confirmed its first case of Covid-19 in Codogno, an hour’s drive south. Three days later, Bergamo’s province announced its first two cases, located in the town of Alzano Lombardo.

Still, as it was their habit, the Gargantini family gathered to watch TV and drink tea as 9-year-old Marta returned from school. Five days later, Giancarlo complained he had still not been able to shake off a jelly-like sensation in his legs and a persistent fever.

He had no cough though, which reassured Sara. “Both my daughter and I had had heavy flu-like symptoms a few weeks earlier, so I thought it must have been a seasonal flu,” she tells The Independent.

But soon Giancarlo started to feel faint and lose his breath. For the first time, he had missed Marta’s horse race and bailed on the weekly dinner with the Alpini, the army’s mountain infantry, where he cooked and reminisced with fellow comrades.

An ambulance was later called and took him to the Pesenti Fenaroli hospital, but he was discharged a few hours later and sent home. Tests showed he had a persistent fever and the early stages of pneumonia. Doctors gave him a prognosis of seven days.

“He was already dead by then,” says Sara, holding back tears.

No test was conducted to ascertain whether he had contracted the virus. The hospital is now known to have been a hotspot for Covid-19.

Bergamo’s first two coronavirus cases were detected inside its wards. The hospital was forced to shut for a week, but when it reopened, it had not been properly sanitised. It was after the hospital opened its doors again that Sara’s father was taken in.

Guido Marinoni, the president of Bergamo’s order of doctors, has since confirmed the hospital mishandled the situation, with infected doctors becoming strong accelerators in the spread of the deadly virus.

Sara’s final goodbye could not get past the wheezing noise of the oxygen mask.

“I was shouting on the phone, but he could not hear me.”

The Gargantini family was unable to hold a funeral, as all religious ceremonies have been banned to limit contagion. Due to the unprecedented number of deaths, coffins have piled up in churches until army vehicles ferried them to morgues in less-affected regions.

Giancarlo’s family does not know where his remains are located. The impossibility to mourn him has made the death seem unreal.

“It feels as if he disintegrated, disappeared all of a sudden,” she says.

In one family, three deaths in two weeks

Roberto Micheletti, 87, known as “Berto”, was a carpenter in the town of Bagnatica. His workplace, a garage in the compact three-storey house where he lived with extended family, is decorated with his nephews’ drawings and a cutout of Pope Francis benevolently waving his hand.

The day Berto died, on 18 March, his wife Rosa Fretti, who was about to turn 80, was taken to the hospital. Every Sunday, Rosa cooked homemade lasagne and, by means of her tireless work, kept the family together.

“It was always homemade food, that was her thing,” her niece Lorella Carminati tells The Independent.

The day Rosa died, on 24 March, her brother Valter had been taken to hospital.

“It felt like the cycle was never going to stop, we were stuck in a nightmare,” Carminati, who is the daughter of Rosa and Valter’s sister Maria, says.

Valter, a nurse who had spent his life tending to others, was now bed-bound. Before falling ill, he had resolved to resume his profession and join the ranks of retired nurses called to join in the battle against Covid-19.

When Valter died on 30 March, contagions in Bergamo totalled 8,664. For Carminati, who lost three family members in the span of two weeks, the loss inflicted is incalculable.

“We knew they weren’t immortal, but they shouldn’t have had to die alone, without even a funeral, after all they have done for us,” she says.

What went wrong in Bergamo?

The province of Bergamo has officially registered more than 2,200 deaths since the beginning of the outbreak.

Estimates place the real figure at 4,800, suggesting as many have died without a test confirming the presence of the virus.

Bergamo, like the rest of Lombardy, went into lockdown on 8 March. But specific measures were never taken for the province, despite the spike in infections.

In February, prime minister Giuseppe Conte had cordoned off and quarantined 10 towns in Lodi, a province roughly 70km south of Bergamo, and effectively established Italy’s first localised exclusion zone – or “red zone”.

In these zones, patrols and roadblocks were set up and people were stopped from entering or leaving, thereby cutting it off from surrounding areas.

The town of Vo’ Euganeo, in the neighbouring Veneto region – roughly 250km east of Bergamo – followed suit, but the province of Bergamo was exempted from localised restrictions.

But by 1 March, contagions in the Bergamo province had soared to 220.

The mayors of Nembro, Alzano Lombardo and Albino in Bergamo informed their towns that they were about to become a new red zone, and the army swept in. The area surrounding Codogno – where the first patient had been detected – had been cordoned off as contagions hit 50, and the residents of Val Seriana thought they were next in line. But when it came to locking down Bergamo – an area home to 376 factories yielding €850m of profits a year, both Lombardy’s regional authority and the central government backpedalled.

The desire by both the central and the regional authorities to protect Italy’s economy – and the interests of powerful industry owners in the area – are thought to have been behind the U-turn.

The regional authority led by Attilio Fontana and the central government of Giuseppe Conte have been trading accusations, pointing fingers at each other over whose responsibility it was to establish a “red zone”.

“We want to understand if what happened is someone’s responsibility or if it was just a tragic mistake,” Fusco, who founded “Noi Denunceremo” after the death of his grandfather, says.

“If it’s the former, we want justice to take its course.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments