How Britain came to the brink of leaving the European Union

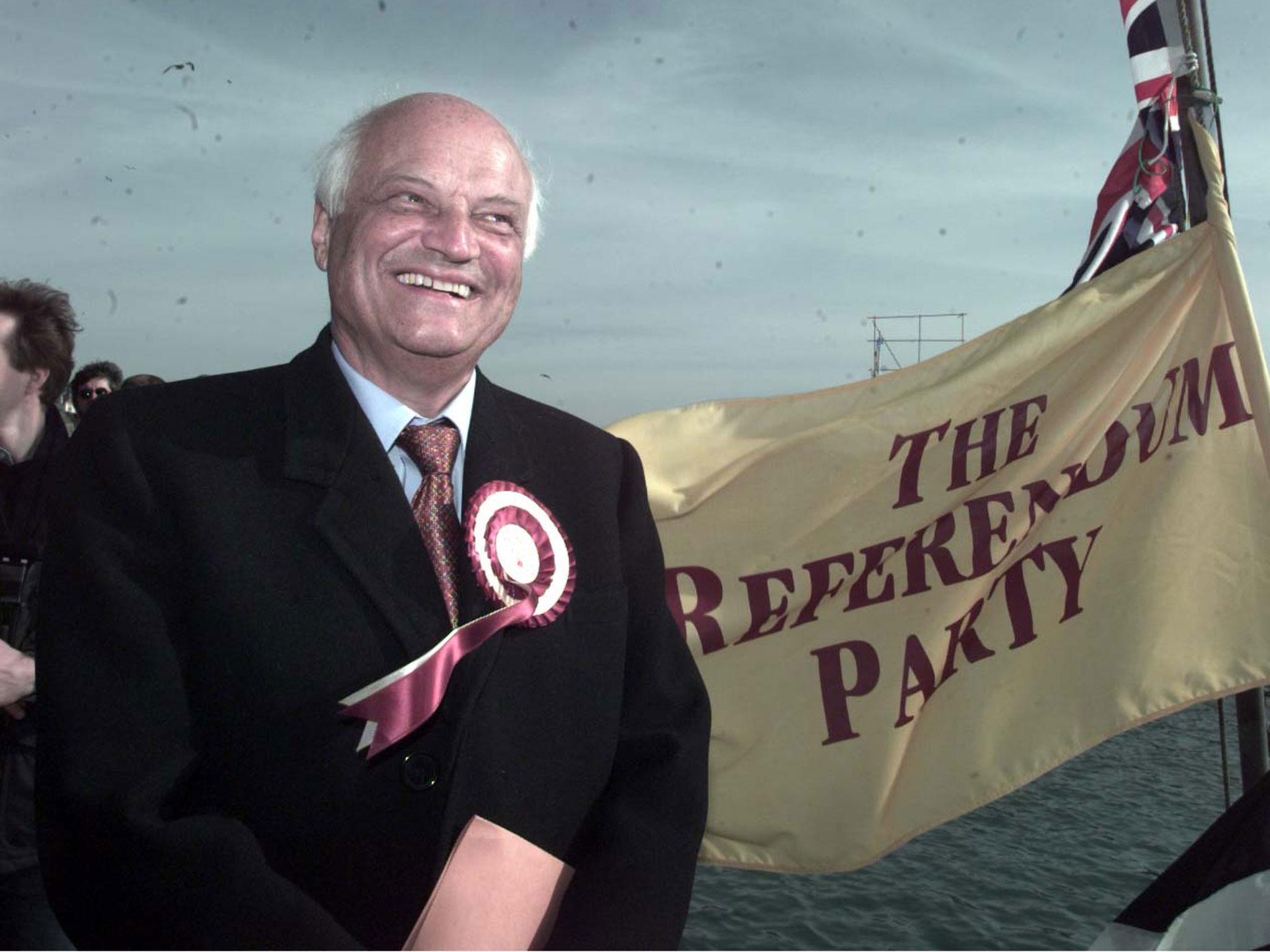

With the polls showing a narrow victory for Vote Leave, Sean O’Grady looks back at the early eurosceptics that got Britain here. Most notably, the man who was Nigel Farage before Nigel Farage; Sir James Goldsmith

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Very soon we may all be asking ourselves – whether we like it or not – how Britain came to vote to leave the European Union, an institution that we have been part of for almost half a century, and which had seemed an immutable fact of political, cultural and economic life.

How indeed. The short term answers are obvious enough, and can even be explored now. Why was the Remain campaign so dominated by economics and “fear”? So many bogus, but precise-sounding stats? Why did they have no answer on the immigration issue, a failure tacitly conceded already by Theresa May, looking desperately to promise further moves on movement of people. Why were solidly centrist, moderate, sensible politicians from David Cameron to Harriet Harman to Tim Farron to Nicola Sturgeon ignored, and the mavericks – Nigel Farage, Michael Gove, Boris Johnson – heeded so readily? Who were the spin doctors who plotted this audacious coup? There will be an orgy of blame-throwing whatever happens, so close is the result. It is a moment to recall Napoleon’s remark that success has many parents, but failure is always an orphan.

And yet of course the roots of British euroscepticsm run much, much deeper, though it was once more pronounced on the left of politics than the right. Not so for two decades or more now, though. For Sir John Major, his interventions in the campaign were personal as well as about statesmanship; he more than anyone suffered for the Tory splits on Europe that marred his premiership in the 1990s. We all know about the “bastards”, some still causing him grief – John Redwood, Iain Duncan Smith, Peter Lilley – but we seem to have forgotten about that other figure from that era, the man who really established euroscepticism as an independent political phenomenon on its own terms, stoked the demand for a referendum on Europe, and campaigned for Britain to get out of the “superstate” decades before it had much chance of turning into reality. The man who was Nigel Farage before Nigel Farage; Sir James Goldsmith.

For it was Goldsmith's Referendum Party that really got the idea of a popular vote on the map, twenty years ago. Yes, the UK Independence Party had been founded as early as 1991, during the great Maastricht Treaty negotiations by the thoughtful academic Alan Sked, but was for a considerable time merely a slightly eccentric libertarian pressure group. Goldsmith’s cash – he was one of the richest men in the land if not the world – turbo-charged the cause of British euroscpeticism, untrammelled by any considerations of loyalty to a conventional party or leader, or many short-term political calculations. It was the beginning of a great peasants’ revolt against the British establishment, or at least so it has been painted – after all most of its leaders, from Goldsmith through to Boris, have been wealthy and well-connected men.

Where did Goldsmith make the money to bankroll an entire political party, albeit a relatively small one? The answer is that he started rich and got richer. His father owned hotels, and was also a Conservative MP, and, so the story goes, James Goldsmith won about a quarter of a million pounds in today’s money on a horse racing accumulator that cut short his time at Eton. Apparently he declared to his fellow schoolboys: “a man of my means should not remain a schoolboy.” Later on, he got into food. According to the official James Goldsmith website, his Cavenham foods company employed at its height some 60,000 people, and “with sales of £1.6bn by 1977, it was three times the size of either Sainsbury or Tesco, making it the third-biggest food company in Europe”.

Goldsmith’s trick, if that’s the right word for it, was to buy undervalued and sometimes badly-managed famous brands and try and get the maximum value out of them. Doing this in the 1970s he might qualify for the catchphrases of the time – “asset stripping” and “the unacceptable face of capitalism”. It was highly appropriate that one of Cavenham's products, the savoury spread Marmite should play a small but symbolic role in the rise for Goldsmith and the making of his fortune. Like Marmite, this was a man the rest of the world either loved or hated. It didn’t seem to matter overmuch to him, as he applied his financial skills in a string of takeovers and restructures, each one adding to personal wealth of some £1.2bn or so. He anticipated the stock market crash of 1987, proving once again his shrewdness. It is fair to say that, domiciled in Mexico, he was also careful about his tax planning.

He had other fun along the way too, though not everyone joined in. Goldsmith, maybe apocryphally, is said to have once quipped: “When a man marries his mistress, he creates a vacancy”. Without wishing to sound like an apologist, it wasn’t such a strange thing to think in those days in those rather louche circles, and “Sir Jammy Fishpaste” spent many an evening at his great friend John Aspinall’s Clermont Club. Champagne, cigars, casinos about sums it up. In any case, Goldsmith married three times, his widow Lady Annabel surviving him, and rumours about his romantic exploits still reverberate. Annabel, daughter of the then Marquess of Londonderry, had an affair with Goldsmith for about a decade before leaving her husband Mark Birley for him: “Mad about Jimmy. Loved Mark desperately” she later explained. It was Birley who named the London nightclub after her.

Goldsmith’s political exploits still reverberate, too. I still possess, among my political nick-nacks, a copy of a Referendum Party video (a VHS cassette as it happens, which I agree dates it and me). Goldsmith paid for a copy to be posted to every household in Britain – about 24 million of them. Presented by a bloke off That’s Life!, I didn’t find it especially persuasive at the time, and it seemed a bit irrelevant in those days of Blair-mania and before the single currency euro turned out to be such a disaster. Europe had only just completed its latest round of expansion, allowing in Austria, Finland and Sweden, prosperous and easily digested economies. The accession of Poland and other former communist states with the movement of people across the continent was almost a decade away. The “1992” British-inspired Single Market project had not long been completed, and seemed to be contributing to healthy economic growth. The Maastricht Treaty had been agreed, but Major had negotiated key “opt outs” that kept Britain aloof from the single currency, the “social chapter” and retained the UK veto in home affairs and justice matters. There was not, in other words, any compelling feeling that the European project, though irritating and intrusive, was yet a failure or a threat to British living standards as well as democracy.

And yet Goldsmith made his mark, not just for the memorable scenes of him jeering David Mellor at the count in Putney in the ’97 election – Mellor being one of many senior Tories to end their careers for good that year. In that great rout of the Conservative Party (their worst result since 1832), two trends then emerged. First, the dominant Heathite pro-European wing of the party started to seriously wither away, as the knights of the shires retired and were replaced by younger candidates, the “sons and daughters” of Thatcher, who of course was then making her opposition to the EU vocal and defiant. Only Ken Clarke was prepared, then as now, to stick up for the ideal Europe with much passion. At that time, not quite a decade after the regicide that had her leave Number 10, her word was gospel to many of those who came into politics to emulate and support her. Her endorsement of William Hague as leader to succeed Major in 1997 was an important one; Hague beat Clarke, and made no secret of his euroscepticism (he has been notably mute more recently) and went on to launch the Tories disastrous “Save The Pound” campaign at the 2001 General Election.

Still, a combination of Goldsmith's Referendum Party, the Tories’ admittedly often ineffectual campaigning, public opinion and divisions in his own ranks pushed Blair towards a more cautious view on Europe. He promised a referendum on joining the single currency, the euro, and, in almost open conflict with his Chancellor, Gordon Brown, set out the “conditions” that would have to be met before we joined. Blair’s public reputation, tarnished as it is today, (and maybe more so after the Chilcot Report is published a month from now) would stand still lower had he succeeded in getting us into the euro. He might have managed in his first dizzy days in power, yet he missed his chance, and, even Europhiles would agree, that was just as well.

So the idea of a referendum on Europe began to be part of the common discourse across the parties in the 2000s. Even Nick Clegg soon proposed an “In/Out” referendum to settle the issue for good, in the mistaken belief that, surly as the British public may be, they would never go that far. When David Cameron tried to get himself out of a tight corner by offering his restless backbenchers a referendum, why did he do so? Simply because Ukip was threatening to take so much support from him that he feared for his own future, yes, but also that of his party. He might have resisted it, and surely would have if he could see how it would turn out; but such was the weight of public opinion behind it, first expressed in that Goldsmith adventure of the 1990s, that he could not resist. If he had, he might have been toppled and replaced by someone who was more enthusiastic about giving the voters their say. We would still be voting next week.

Goldsmith’s Referendum Party also got people into the idea of voting for a pure anti-European party, breaking down old party loyalties and paving the way for the Farage-led Ukip “insurgency” a decade or so on. Goldsmith only garnered about 3 per cent of the vote in 1997, but that was 3 per cent more than any previous effort (Ukip scored just 0.3 per cent that year), and a succession of European elections soon allowed Ukip to scoop the eurosceptic electoral pot. Critically, the Referendum Party, which was disbanded after the 1997 election, though its spirit and above all its purpose lived on, attracted votes from Eurosceptic Labour and uncommitted supporters.

By that time Labour’s leadership had moved firmly into the pro-European side of the argument, greatly encouraged to do so by the late 1980s European Commission presidency of Jacques Delors and his championing for the “social dimension”, i.e. trade union power and protection for workers. That was famously resented by Margaret Thatcher – “Socialism by the back Delors” – in her Bruges speech as far back as 1987: but was nectar to the Labour establishment. Blair tore up Major’s opt out, signed up to the “social chapter” and today Labour figures such as Jeremy Corbyn, Neil Kinnock and Tom Watson use protection of workers’ rights as the principal reason they now support something once derided by their forebears (actually including a younger Corbyn and Kinnock) as a capitalistic “bosses’ club”. However, as the European adventure turned more and more ugly, and Britain left its legacy as the “poor man of Europe” far behind, the attractions of the EU started to wane. As China, India, Korea and other emerging economies started to challenge the whole world, EU workers’ rights looked more like a cause of poor productivity, low growth, unemployment and “eurosclerosis” – the underlying reasons for the euro crisis from 2010. Had Helmut Kohl and Francois Mitterrand not forced the pace on integration and the euro; had Europe’s eastern expansion as far as Romania and Bulgaria been better managed, had the 2001 “Lisbon agenda” of liberalisation and reform been implemented things, might have played out differently.

Goldsmith himself died not long after the 1997 general election that he had played such a prominent role in. Journalists do not often speak well of him, as he was notoriously litigious and almost bankrupted Private Eye, who dubbed him, at their politest, “Goldenballs”. His son, Zac, made it into parliament as a Conservative MP not far from Putney, but of course failed in his recent bid to succeed Boris Johnson as Mayor of London. A bright and talented figure, he may yet enjoy greater political success, as well as the celebrity status enjoyed by others of his clan, such as sister Jemima, but he is unlikely to emulate his father’s abiding, though neglected, political legacy.

The original Tory eurosceptic – the great grandfather of the current wave – was Enoch Powell. Long ago he characterised the attitude of the British people to the then European community as one of “morbid antipathy”. Powell was a fanatically devoted parliamentarian, who did not believe that a referendum was a legitimate tool for decision-making (and even believed that no parliament had a right to abolish the powers lent to it by its electorate and send them over to Brussels). It was another Old Testament prophet, this time on the left, Tony Benn, who championed the idea of a referendum, not least as the easiest way to get a Labour government to take Britain out of Europe (membership of the EU being incompatible with a planned socialist economy). But neither had a political vehicle of their own to push their European agenda more powerfully forward. Goldsmith, and later Farage, provided that transport. Thus does the ghost of Goldenballs haunt us all.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments