Let down by government, Greek voters expected to replace Tsipras with centre-right

Analysis: New Democracy are expected to win the most seats, but will they get enough to form a coalition?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There’s a general election in Greece tomorrow but, aside from a few roadside posters, it would be easy for visitors to pass through without realising.

In contrast to the huge demonstrations that were broadcast on news stations around the world when the current ruling party – radical leftists Syriza – swept to power in 2015, everything feels remarkably subdued.

The current government, lead by charismatic Alexis Tsipras, rose to power with a populist, anti-establishment message several years into the financial crisis that has engulfed Greece for a decade.

However, he disappointed many of his supporters when he ignored the results of a referendum on a bail-out package, and adopted the same austerity policies he had previously stood against. Now, it looks as though the country’s traditional centre-right party, New Democracy, will take power, having won the highest vote share in the recent European and local elections.

“Syriza supporters are disappointed, New Democracy voters are not too enthusiastic about voting New Democracy, and everybody knows the result already,” said Aris Hatzis, a political commentator and professor of philosophy and law at the University of Athens.

“The only question is whether they will get a majority or form a coalition government.”

Prior to Syriza, Greek politics was dominated by two major parties – New Democracy and centre-left Pasok.

However, this all crumbled when both parties’ mismanagement of the economy lead to the worst-ever recession ever experienced by a developed nation.

Given that Greeks still are still suffering – youth unemployment is at 40 per cent and the economy managed a sluggish growth of just 1.9 per cent last year – why are they turning back to a party that helped cause the situation?

“New Democracy is responsible for both the crisis and for not dealing with it efficiently from 2012 to 2014 [when they were in power],” explained Mr Hatzis.

“It is more conservative than the average European party. It has more nationalism and is closer to the Greek Orthodox church. But the thing is their leader.”

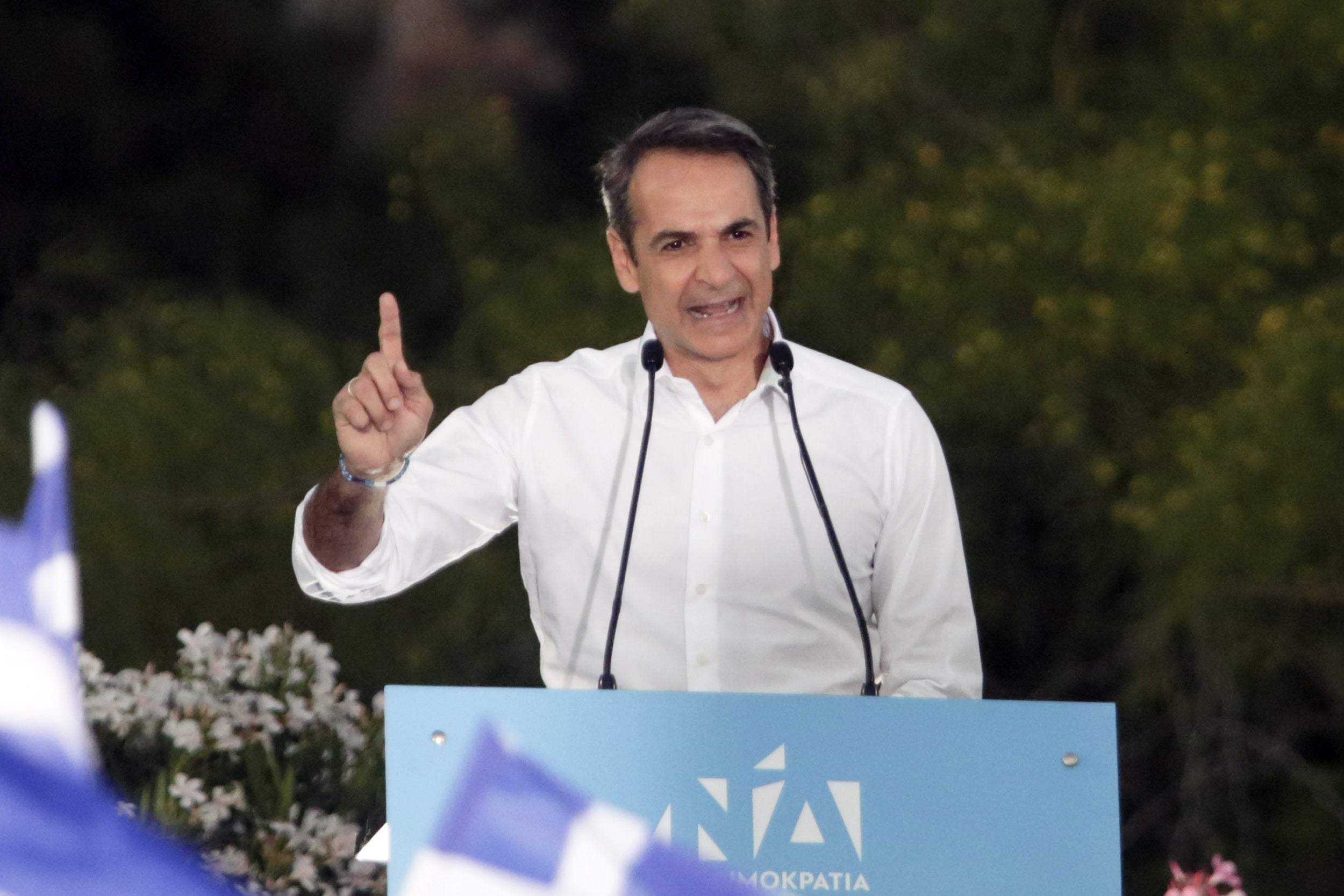

Kyriakos Mitsotakis, who will likely become the next prime minister, is viewed by many as a pro-EU liberal.

He has promised to cut taxes, overhaul Greece’s private sector and make the country more enterprise friendly – currently, it is one of the toughest places in Europe to run a business. His success has been hailed around the world as a return-to-normal for Greece and a defeat of populism.

However, his party still indulges in socially conservative policies and the type of anti-immigrant rhetoric more commonly associated with the far right – just recently, it announced it will assign child benefits according to the parents’ nationality.

“[Mitsotakis] has a chance to turn New Democracy into a moderate European-style party,” said Mr Hatzis. “The only problem is he is leading a party that he cannot totally control.”

I think people want to return to something that feels safer because things have been so unstable

One interesting aspect of Greek politics is that young voters are backing the centre-right in the same numbers as their parents – 30.5 per cent of 18-24-year-olds voted for New Democracy in the general election, similar to the population as a whole.

One of these is 22-year-old Tasos Stavridis, a political science student from Thrace in northern Greece. He blames New Democracy for the crisis, but believes Mr Mitsotakis is different to the politicians of old.

“He’s made a lot of changes, the people in the party now are new and young. People abandoned New Democracy, but they are returning because we have faith in Mitsotakis. We think he can be a new start for the country.”

Mr Stavridis said he hopes the new government will lessen the country’s notorious bureaucracy and grow the private sector.

“We need to escape the [financial] situation we are in,” he added.

One person going against the grain is 31-year-old Elvira, a software developer from Athens. Having supported Syriza in 2015, she is considering voting for the tiny, radical left Antarsya.

“I really do not want a conservative government, so I thought about voting for Syriza again,” she said, declining to give her full name. “But I’m disappointed in them so I find it more moral to vote for a small party that I relate to.”

Elvira said she is also “very disappointed” to see the country turn rightwards.

“I think people want to return to something that feels safer because things have been so unstable.

“After Syriza most people hoped for change, and it’s like they don’t believe in change any more … I think [young people] are voting for financial issues and overlooking the social issues we face in Greece.”

Syriza supporters are disappointed, New Democracy voters are not too enthusiastic about voting New Democracy, and everybody knows the result already

One positive of the elections is that the country’s neo-nazi Golden Dawn, currently the third largest party in parliament, is expected to win less votes.

According to Daphne Halikiopolou, associate professor of politics at the University of Reading, this is partly because the newly-formed far-right Greek Solution party split their vote share, but also because New Democracy’s anti-immigration line and opposition to the recent Macedonia name deal have attracted far-right voters.

But Halikiopolou cautions that any party that wins will face a tough job.

“Syriza learnt that it’s easy to get elected by making all these promises, but once you get in power you have to actually deliver,” she said.

“People are rallying for New Democracy now but when they get in power they have to deliver too, otherwise in four years’ time we could just be in the same position we are now.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments