Ghosts of the Paris riots: France waits to see if court clears police officers of failing to help boys whose deaths sparked 2005 unrest

The death of two boys while being pursued by police sparked cataclysmic unrest in 2005. Now the country is on edge again as a court decides whether the officers could have saved them

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

The French internal security service made an anxious telephone call. “What are the chances of riots in Clichy-sous-Bois next Monday?” Mehdi Bigaderne was asked.

Mr Bigaderne, 32, is the Assistant Mayor of Clichy, a suburban town which is 10 miles and 100,000 light years from the boulevards and brasseries of Paris. It was here that the “Paris” riots began almost a decade ago. During three cataclysmic weeks in October and November 2005, the violent unrest spread to the banlieues, or suburbs, of almost every large town in France.

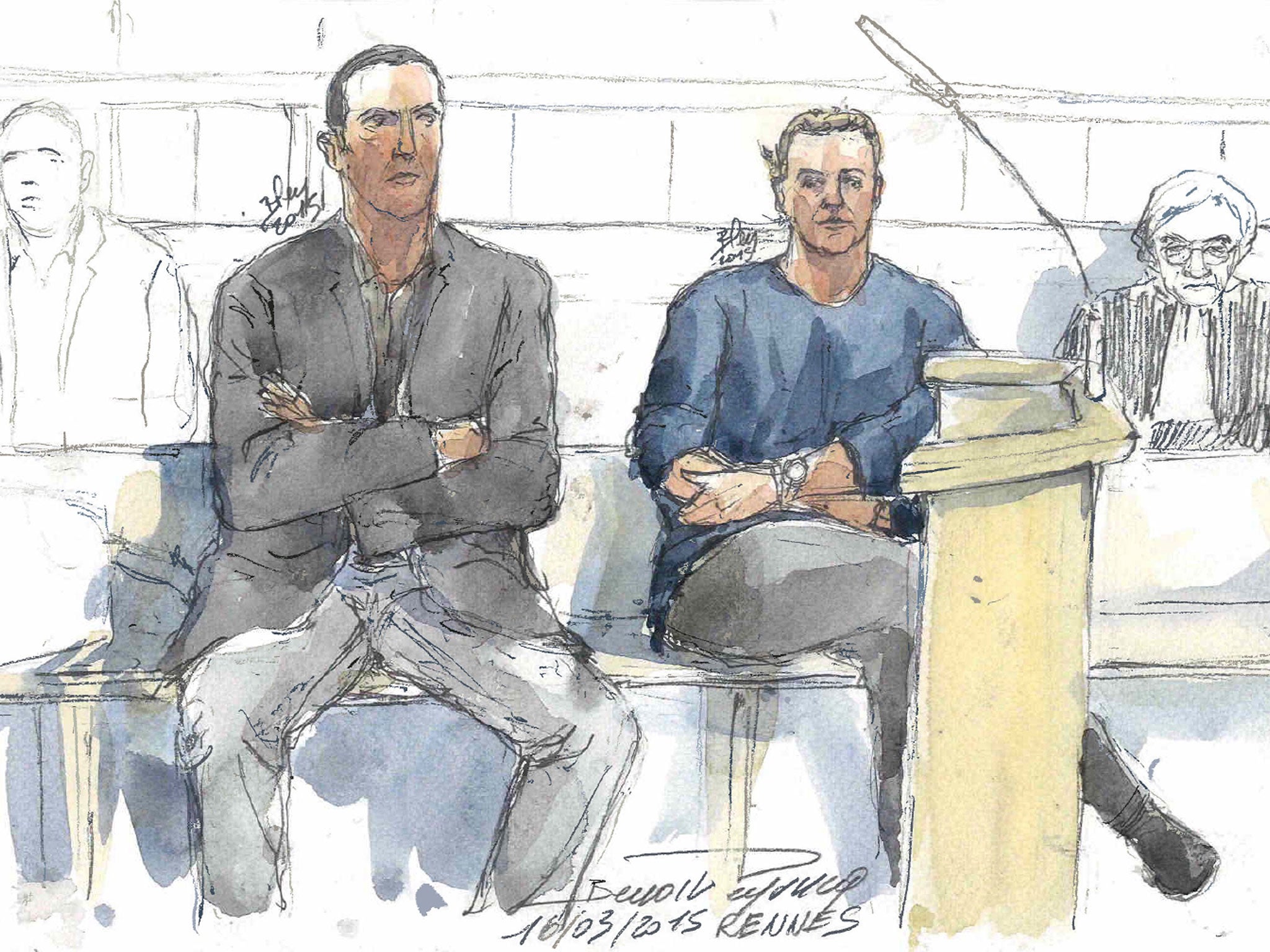

On Monday a court will decide whether two teenage boys whose deaths provoked the riots could – and should – have been rescued by two police officers. It is widely expected that the court, sitting in Rennes, 200 miles away, 10 years after the event, will clear the two officers.

Mr Bigaderne, who grew up with one of the dead boys, thinks that would be a great mistake.

“There is a terrible burden on the shoulders of the judges,” he says. “People here and in similar places all over France are waiting and watching for this judgment. They have been waiting for 10 years.

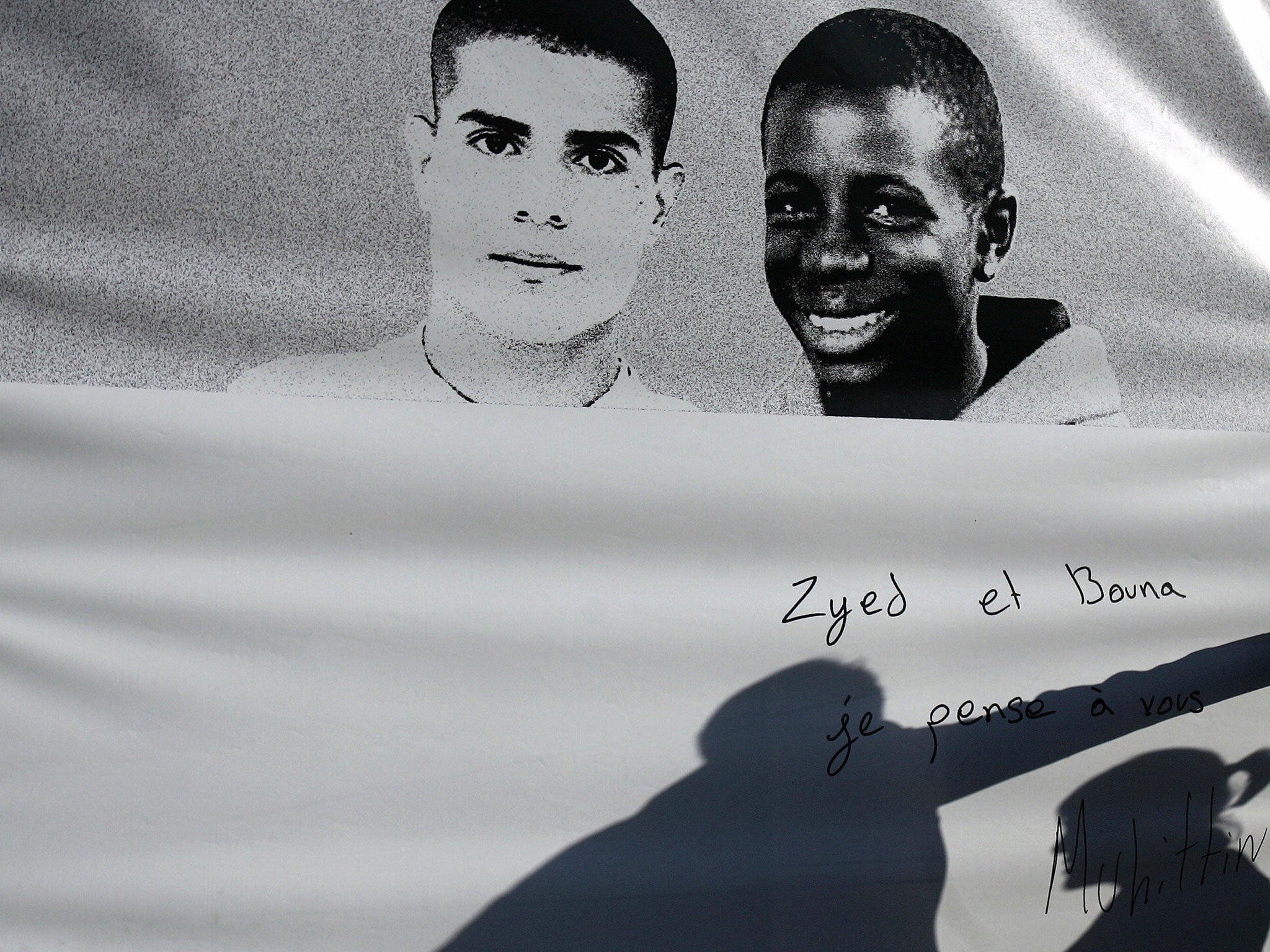

“No one wants the officers to receive a harsh punishment. We want to see whether justice exists in this country for people like Bouna and Zyed and tens of thousands like them.”

So what did Mr Bigaderne tell his recent caller from the Direction Générale de la Sécurité Intérieure, the French equivalent of MI5? If the court in Rennes clears the two officers, will there be riots in Clichy-sous-Bois on Monday?

“The generation that went out on to the streets in 2005 has moved on,” he tells The Independent. “Some have started families. Some have jobs. To the younger kids, it is all very distant. I don’t think they will react violently.

“On the other hand, if there was another spark – another incident, involving police, here or in another banlieue – yes, I fear that the whole thing could explode again.”

On 27 October 2005, a dozen teenage boys from Clichy-sous-Bois, from a jumble of racial backgrounds, were chased by police for no special reason. They ran away because they feared the brutality of the police. The police chased them because they ran away. In March, the court in Rennes heard that Bouna Traoré, 15, and Zyed Benna, 17, were separated from the rest, with a friend, Muhittin Altun, 17. To escape, they climbed a 13ft-high wall into an electricity substation. All three received massive electric shocks. Bouna and Zyed died; Muhittin survived, seriously burnt.

Two police officers were tried for “failing to come the help of a person in danger”. Sébastien Gaillemin, 41, was accused of chasing the boys and then abandoning them to their fate. Stéphanie Klein, 38, who was a trainee in charge of the local police switchboard that day, was accused of failing to issue an alert. Both denied that they knew that the boys were in danger.

The cases took a decade to come to court because the state prosecution service refused on three occasions to bring charges. France’s highest court finally ruled that a trial should be held. In Rennes in March, the state prosecution again insisted that there was no evidence to convict the two officers.

So what has changed in the past 10 years in the multiracial banlieues that surround Paris and most other French cities? On the surface, little. The banlieues are still a patchwork of prim bungalows, grim public housing estates, fast-food joints, motorways, gang warfare, curious remnants of farms and villages, strip malls, forests, carpet shops, scrapyards, abysmal public transport, casual violence, poverty, despair and millions of hard-working people.

Since 2005, Clichy-sous-Bois has become a poster child for the limited government efforts to improve the banlieues. It has gained a police station and an employment exchange. The worst tower blocks have been dynamited or renovated. To reach Paris, 10 miles away, it still takes 90 minutes by slow, meandering buses and then unreliable trains. A new tram line is promised for 2018 and an express metro line by 2024.

Unemployment remains at 20 per cent – twice the national average. In some housing estates, 40 per cent of people are unemployed. Relations between local youths and the police are slightly improved but not much.

Mr Bigaderne belongs to a generation which has tried to work for change. Just after the riots, he founded an association called AC Le Feu (meaning, phonetically, “enough of the burning”). He is now Assistant Mayor of Clichy-sous-Bois, with special responsibility for “social cohesion”. “A few things have changed for the better,” he says. “Other things have changed for the worse.

“The mood in the country worries me. We seem to have become more divided than ever. There are politicians, and not just on the far right, who want to exploit racial fears and Islamophobia. There is also something which scarcely existed in 2005: the identification of some young people with ultra-extreme forms of Islam. There is no use ignoring it. That is a genuine problem.”

American TV reporters spoke in 2005 of a “French intifada”. There was also talk in the British press of “race riots”. Both descriptions were grossly misleading. The French banlieues in 2005 were social ghettos but they were not mono-racial ghettos. Many of the groups of rioting kids consisted of different races – white, black and brown, just like the national football team. The rioters were protesting against police violence or exclusion or they were trying to “out-riot” the hated kids – also white, black and brown – in the next housing estate. They were certainly not rioting in the name of Islam.

In the past 10 years, Mr Bigaderne says, the social landscape has changed. The racial mingling has given way – partly, not entirely – to mono-racial communities. “The Turks stick together. The Pakistanis are very close‑knit. Some of the sub-Saharan African communities live all together,” he says.

The young people who rioted in 2005 identified with their cité, or estate, or with their resentment towards the police or their lack of opportunities. In many cases, that remains true, Mr Bigaderne says. “But there are now kids who have turned to these extreme and violent distortions of the message of Islam.

“Just the other day I heard of a boy, only 14 years old, who has gone from here to Syria.”

The core problem, he says, is the same as it was a decade ago: a muddled or wounded sense of “identity”. In 2005, the great majority of the rioters were French born. So were the Kouachi brothers, who attacked Charlie Hebdo in January.

“The right wing in this country becomes indignant when they see kids waving Algerian or Moroccan flags,” he says.

“The real question that these politicians should ask themselves is: why do kids, who don’t speak Arabic, who have never been to North Africa, identify with countries about which they know nothing? What have we ever done to make them feel French?”

An acquittal of the two police officers on Monday will not bring young people on to the streets, Mr Bigaderne says. It will reinforce their conviction that the promises of the French Republic – especially “equality” and “fraternity” – still do not extend the 100,000 light years from central Paris to Clichy-sous-Bois.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments