Germanwings crash: On the ground in Le Vernet – 'It was a thunderclap in a place that is very quiet and very wild. Not something you forget'

Eyewitness report: 'There were no people. Only parts of people'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Gilles Thezan saw no smoke and heard only a sound like a thunder. But what he saw in the Vallée de la Blanche as he arrived at a desolate crevasse and the remains of flight 4U 9525 lay spread before him will stay with him until his dying day.

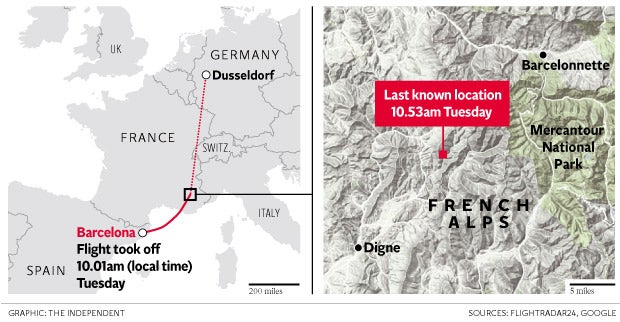

The 56-year-old was among the first to reach the narrow Alpine valley where the Germanwings Airbus A320 plummeted to the ground after its indecipherable 18-minute descent from the safety of cruising height to its final resting place on a rock face at a closing speed of 500mph.

Stood outside the tiny village school and library, which found itself as the backdrop for the aftermath of the third worst air disaster in French history, Mr Thezan said: “Confetti. I can only describe it as confetti – like a giant had scattered paper at a celebration.

“The plane has been torn to small pieces – personally I saw nothing bigger than a laptop computer. It is a very disturbing sight, so many lives ended in a space that you would miss if you didn’t know you were looking for it."

His voice catching slightly, he added: “It is not a nice thing to see. There were no people. Only parts of people. It was hard to look and it is hard to say it. There was no smoke, hardly even an explosion. It was a like a thunderclap in a place that is very quiet and very wild. It is not something you forget.”

Such is the inaccessibility of the valleys that hide behind the imposing Col des Trois Evêchés where the Lufthansa-owned A320 crashed that it is the sort of haven where wolves are able to wander and wild goats graze.

But that isolated calm was yesterday overtaken by the busy thrum of all the paraphernalia brought to bear when a passenger jet on a mundane journey in a part of the world where aviation is considered as perilous as catching a bus falls off radar screens and into a mountain.

In Le Vernet, a small village of 150 people where the main employers are tourism and forestry, the snow-capped hills echoed to the clatter of helicopters shuttling to and fro the crash site and phalanxes of Gendarmerie and mountain rescue teams beginning an arduous, grim task likely to last weeks, if not months.

The immensity of the endeavour – recovering the bodies of the 150 dead and then seeking to piece together from the “confetti” the story of what happened to the A320 – is not easily overstated, according to those who live and work in the terrain. What begins as an engaging landscape of pine trees and guttering mountain streams rapidly gives way to bare craggy mountain, pitted with ravines and crevasses, as it ascends to 2,000 metres and beyond. By nightfall, this was also one of the most closely guarded wildernesses in Europe – dotted with armed Gendarmes who block any progress along the Alpine tracks that wind towards the crash zone. Closer in, other officers are stand sentry around the crash site, guarding it from intrusion by both wolves and unwanted onlookers as investigators begin their difficult work.

Jean Louis Bietrix, a mountain guide from the nearby hamlet of Prads Haute-Bléone who helped bring the first police teams to the scene, pointed to the snow-capped peak that hides the small valley where the passenger jet ended its journey from Barcelona to Düsseldorf. He said: “It is difficult to reach. With a good 4x4 vehicle you can get within a kilometre or two. But then it is a 20-minute hike to the valley, and once you are there it is treacherous. It is not a place you can land a helicopter. The gradient is 80 per cent in places and so many pieces scattered over the area. Bits. Just bits. It is horrible to think that something as large as an aircraft can be reduced to pieces no bigger than a car door.”

Mr Thezan, a petrol engineer, added: “It is below the snow line but this is not the sort of place you venture into lightly. There can be avalanches and the rocks are perilous. They can fall. This operation brings considerable risk.”

Referring to the Malaysian Airlines flight shot down over the Ukraine last summer, he added: “Even in the Ukraine, there were large parts of the plane that remained. Here it is a far harder jigsaw.”

For both men – a mountaineer and his seasoned colleague – along with their fellow residents, the horror of events of the last 24 hours was still raw.

As the young pupils at the Ecole Pierre Magnan sang their playtime songs and played tag, a detachment from the emergency services was putting the finishing touches to a first-aid shelter on the outer reaches of the playground. Outside it were planted the German, Spanish and French flags in expectation of a visit by President François Hollande, Chancellor Angela Merkel and the Spanish Prime Minister, Mariano Rajoy, as they toured the disaster zone.

But more pertinent was the shrine set up in an annexe of the community library and decked with wreaths for the families of the dead – people who had lost babies, teenage children and so many loved ones on, as the villagers saw it, ground that now immutably belongs to the grieving.

In places like Le Vernet and the adjoining town of Seynes-les-Alpes, the dominant desire was to help, in any form possible. A local mayor said he had been inundated with calls from residents offering accommodation for relatives following reports that hotel rooms in the area had been booked out.

The sense of responsibility to the bereaved also applied to what the forbidding but otherwise ordinary mountain in their midst now stands for.

François Balique, the mayor of Le Vernet, told The Independent: “There are 150 people who live in this village and there were 150 people on the plane. The number is pertinent – the equivalent of our village being wiped away. We take the families of those on that plane to our hearts and tell them that our home in now theirs.

“But there must also be permanence. We will make the mountain a place that is for the families. We are now the guardians of this place and the memory of those whose lives were ended here in a few moments.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments