Former Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk faces challenge at the European Council

The ex-Polish Prime Minister will need to build consensus in the post

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

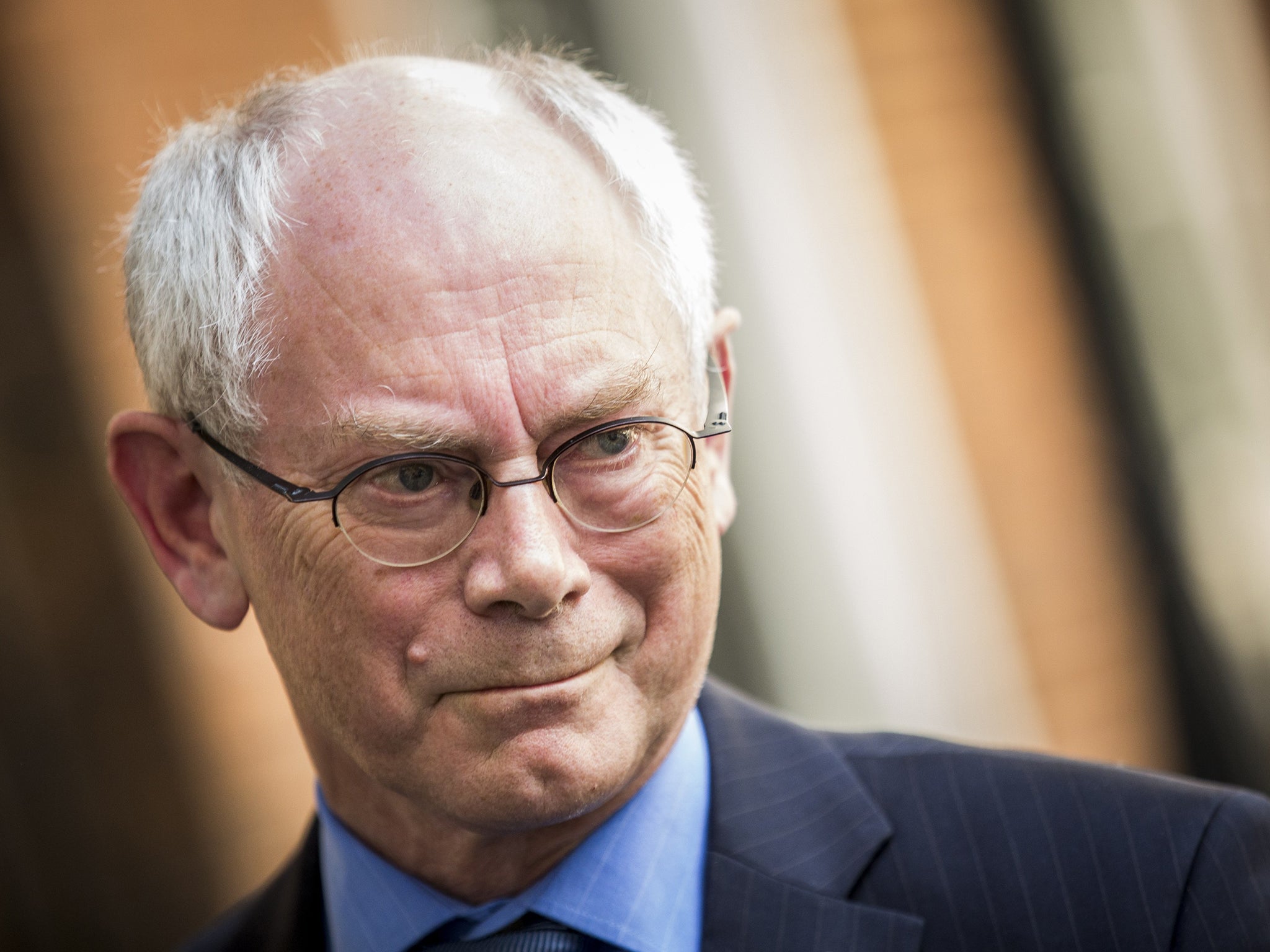

Your support makes all the difference.When Ukip’s Nigel Farage outraged Brussels in 2010 by comparing the incoming European Council President, Herman Van Rompuy, to a “low-grade bank clerk” with “the charisma of a damp rag” he didn’t mean it as a compliment.

But after five years at the helm, Mr Van Rompuy’s low-key approach turned out to be exactly what EU leaders needed during tumultuous times, with the poetry-loving Belgian possessing a skill crucial for success in the job: the ability to leave your ego at the door. “He has a discreet way of operating which I think national leaders appreciate – he wasn’t trying to outshine them,” said Richard Corbett, a former advisor to Mr Van Rompuy who is now Labour’s MEP for Yorkshire and the Humber.

On Monday, Mr Van Rompuy steps down as European Council President, the post that oversees meetings of the 28 EU leaders. He is replaced by Donald Tusk, a former Polish Prime Minister who spent seven years dominating the political landscape in the nation of 38 million people.

Mark Leonard, director of the European Council on Foreign Relations think-tank, called their personal styles “radically different”. As the Belgian Prime Minister between 2008 and 2009, Mr Van Rompuy was forced to constantly mediate between political factions to try to keep a small nation of bickering French and Dutch speakers from splintering in two.

“Van Rompuy is a virtuoso collation builder,” he said. “He’s very thoughtful, he listens a lot, but he also comes from a country and a political culture where getting anything done at all is almost impossible unless you are willing to put hours and hours into coming up with an improbable compromise and reconciling irreconcilable positions.”

All skills perfectly suited to the EU then. Mr Tusk, meanwhile, has more in common with another man briefly touted for Mr Van Rompuy’s job back in 2009: the former British Prime Minister Tony Blair. “Tusk comes from a position where he was in the dominant party for a very long period of time and ruled in a much more hierarchical top-down way,” Mr Leonard said.

The question is whether Mr Tusk can adapt his more forthright style to the challenges of the European Council, where chief among his tasks is stroking egos to try to coax a compromise. “You need to be capable of getting consensus out of 28 prima donnas,” Mr Corbett said.

The European Council refers to the grouping of leaders of the EU member states. While much EU policy-making is done through dialogue between the European Commission, the European Parliament and lower levels of national governments, the big issues eventually find their way to the very top. Every few months the 28 heads of government get together to bicker over topics such as budgets, economic policy and foreign affairs.

“These are people who don’t work together day in and day out, and most of them are used to getting their own way in a national context,” Mr Corbett said. “Suddenly they are in a meeting in which they can’t do anything unless everybody around the table agrees.”

The European Council President sounds out the different options of the leaders before the summits, gauging exactly how far each is willing to bend their positions. He or she can then steer the debate by choosing the order of speakers, then tabling compromises when the inevitable deadlock sets in.

In the past the role was held on a rotating basis, but it became permanent under the Lisbon Treaty of 2007. Mr Van Rompuy was the first person to hold the post, and the consensus is that he has set the bar high. The 66-year-old turned out to be nothing like the dull description that Mr Farage lumped him with, instead possessed with a dry sense of humour and an endearing eccentricity which extended to publishing books of haiku poetry.

But the EU is evolving, and Mr Tusk’s appointment marks a significant shift in the balance of power since the bloc started its rapid eastward expansion just over a decade ago. Mr Tusk is the first leader from Eastern Europe – and from a former Soviet bloc – to hold a top EU job. He has been an outspoken critic of Russia since the Ukraine crisis erupted and his appointment sends a strong signal to Moscow.

A resurgent Russia will not be 57-year-old Mr Tusk’s only challenge. The worst of the eurozone crisis may be behind the bloc, but unemployment remains stubbornly high and economies are hardly booming. Mr Tusk’s track record is promising. During his 2007‑14 spell as Polish Prime Minister he oversaw strong growth in a continent overshadowed by recession. And with surging mistrust in the EU, leaders are hoping that a politician from outside the traditional power bases of France, Germany and the richer north will help bridge some divides.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments