Fall of the Berlin Wall: The guard who opened the gate – and made history

Tony Paterson meets Harald Jager, the man who, amid fear and confusion, took the snap decision to open the Berlin Wall, triggering German reunification

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Tears still well up in Harald Jäger’s eyes when he recalls how he famously gave the order to open the Berlin Wall.

But the tears the former Stasi lieutenant-colonel first shed on that November night 25 years ago came from feelings of humiliation and defeat rather than joy.

Mr Jäger, now 71, is renowned in Germany for being “the man who opened the Berlin Wall”. On the night of 9 November a quarter of a century ago, he was the East German border guard officer in charge of the Bornholmer Strasse crossing point separating the communist East Berlin borough of Prenzlauer Berg from the West Berlin district of Wedding.

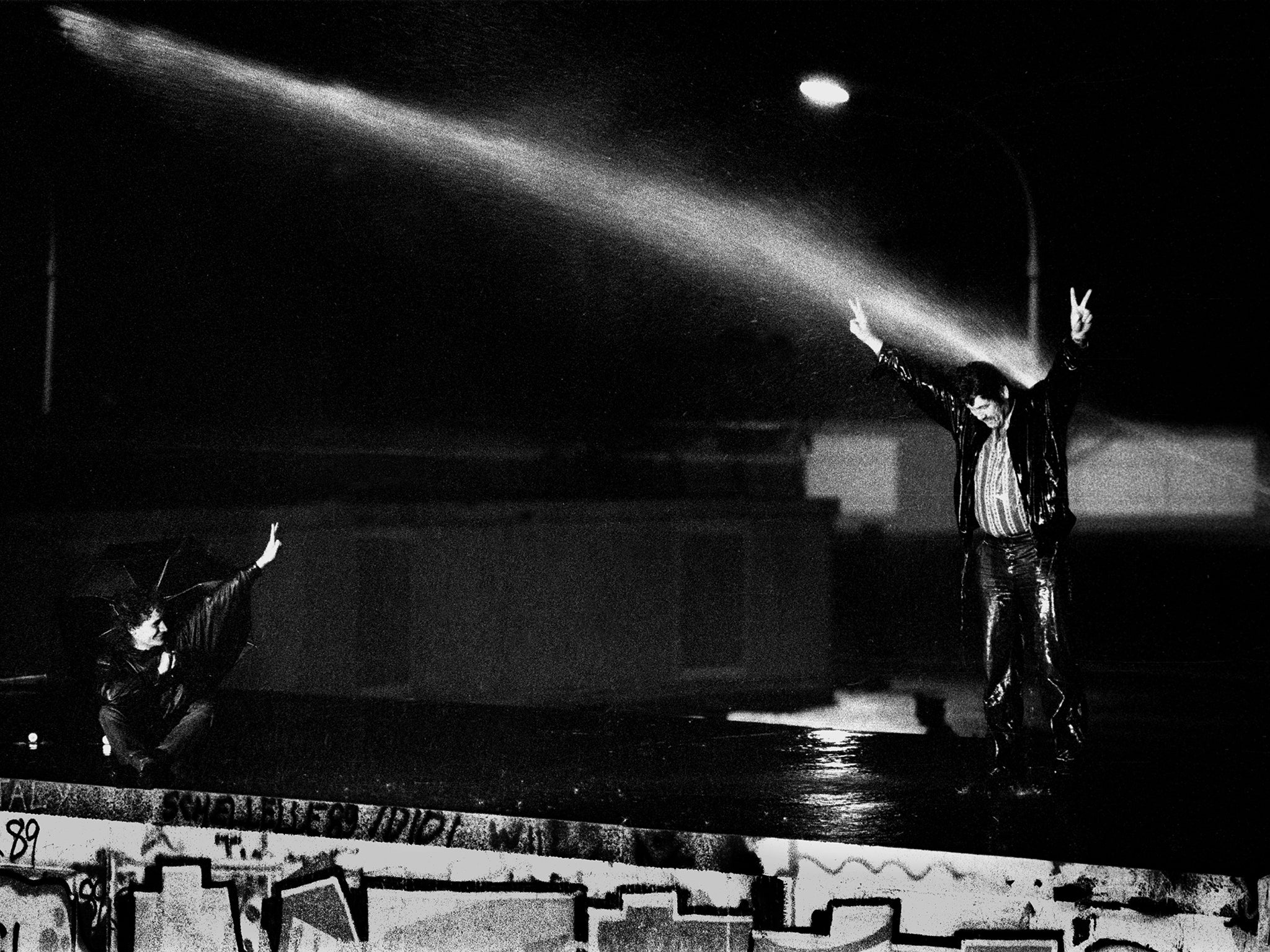

By 11.30 that night he and his colleagues were confronted by an angry and rapidly growing crowd of over 20,000 East Berliners chanting “Open the Gate”. Amid complete confusion, without clear orders and fearing a stampede, bloodbath or both, he took the snap decision to breach the divide.

The career border guard had passionately believed in and even helped to build the Berlin Wall back in 1961. Now, unwittingly, he was ordering its destruction, triggering German reunification. He didn’t know it then, but one of his next jobs would be running a newspaper kiosk just yards from where he now stood.

“After I gave the order, I and the other guards couldn’t believe what we were seeing. We were shell shocked, we felt the world was collapsing around us” he told The Independent in the small communist-era flat he shares with his wife in the village of Werneuchen north of Berlin.

“We stood there and watched our citizens leaving en masse. These were our people. We cried. We felt betrayed by our superiors. It was the terrible realisation that not only the system and our leaders had failed. We had too,” he added.

It wasn’t until about half an hour later when the vast tide of East Berliners – cheering, clapping, hooting and weeping with emotion as they poured westward – reached full ebb, that the penny dropped for Mr Jäger and his colleagues. “The crowds won us over with their euphoria, we realised that they were overjoyed and our tears of frustration turned to those of joy,” he said. “At that point one of the guards came up to me and said, Harald, I guess that was it with East Germany. It suddenly dawned on me that it was.”

East Germany’s end had been proclaimed, albeit in a garbled statement, by East Berlin politburo member Günter Schabowski some four hours earlier. Buckling under the pressure of a huge anti-communist demonstration in Berlin five days before and a mass exodus of East Germans across the now open Iron Curtain on Hungary’s border with Austria, the regime knew that easing its ban on travel to the West was its only slim chance of survival.

Mr Jäger was in a Stasi canteen grabbing a bite to eat at the time. Sitting in front of the canteen TV set he watched in disbelief: Schabowski had first announced on state-run television that East Germans could now travel to the West providing they obtained the correct travel documents from the authorities. But then he suddenly declared that they could do so “immediately and without delay”.

“I almost choked on the roll I was eating. I thought ‘what is this nonsense all about?’” By the time he reached the Bornholmer Strasse guard post, small knots of inquisitive East Germans had started to gather outside. They were anxious to find out whether they could travel West. Mr Jäger telephoned his superior, Stasi Col Rudi Ziegenhorn, for advice but was bluntly instructed to send away anyone who did not have the right travel documents. “Why are you calling me about such nonsense?” Mr Jäger was asked.

But by 8pm West German television was interpreting Schabowski’s statement with the news headline: “East Germany opens its borders to the West.” The gathering of East Germans at Bornholmer Strasse was fast becoming a crowd. Mr Jäger made more increasingly desperate phone calls to his superior. “I have no order from above for you,” Ziegenhorn told him.

By 9pm the crowd had become so big that Mr Jäger was beginning to panic: “We have to do something,” he shouted down the phone.

He was then ordered to defuse the situation by letting the noisiest East Germans leave the crossing point for West Berlin. The aim was to make it impossible for them to return by rendering their passports invalid with a special stamp. “I realised then that I was doing something which was illegal even in East Germany,” he said. The tactic soon backfired. The crowd, seeing that the noisy were allowed West, started to get noisier.

The other guards, realising that East Germany’s entire military and political apparatus appeared to have lost control, begged Mr Jäger to take action. All of them were armed with pistols and Kalashnikovs were on hand in the border post hut. But Mr Jäger feared a bloodbath even more than the possibility of a stampede which seemed imminent. Shortly after 11.30pm he gave the order “Open the barrier” and the human tide flowed west until dawn.

At the end of his shift, Mr Jäger called his sister: “It was me who opened the border last night,” he told her. “You did well,” was her reply. The rest is history.

But for Mr Jäger the experience was an ideological trauma. His father was one of East Germany’s first border guards. After the Second World War, he was granted early release from a Soviet prisoner of war camp in Siberia because he had signed up for the job. His son grew up to be a communist and joined the border guards as his father had done.

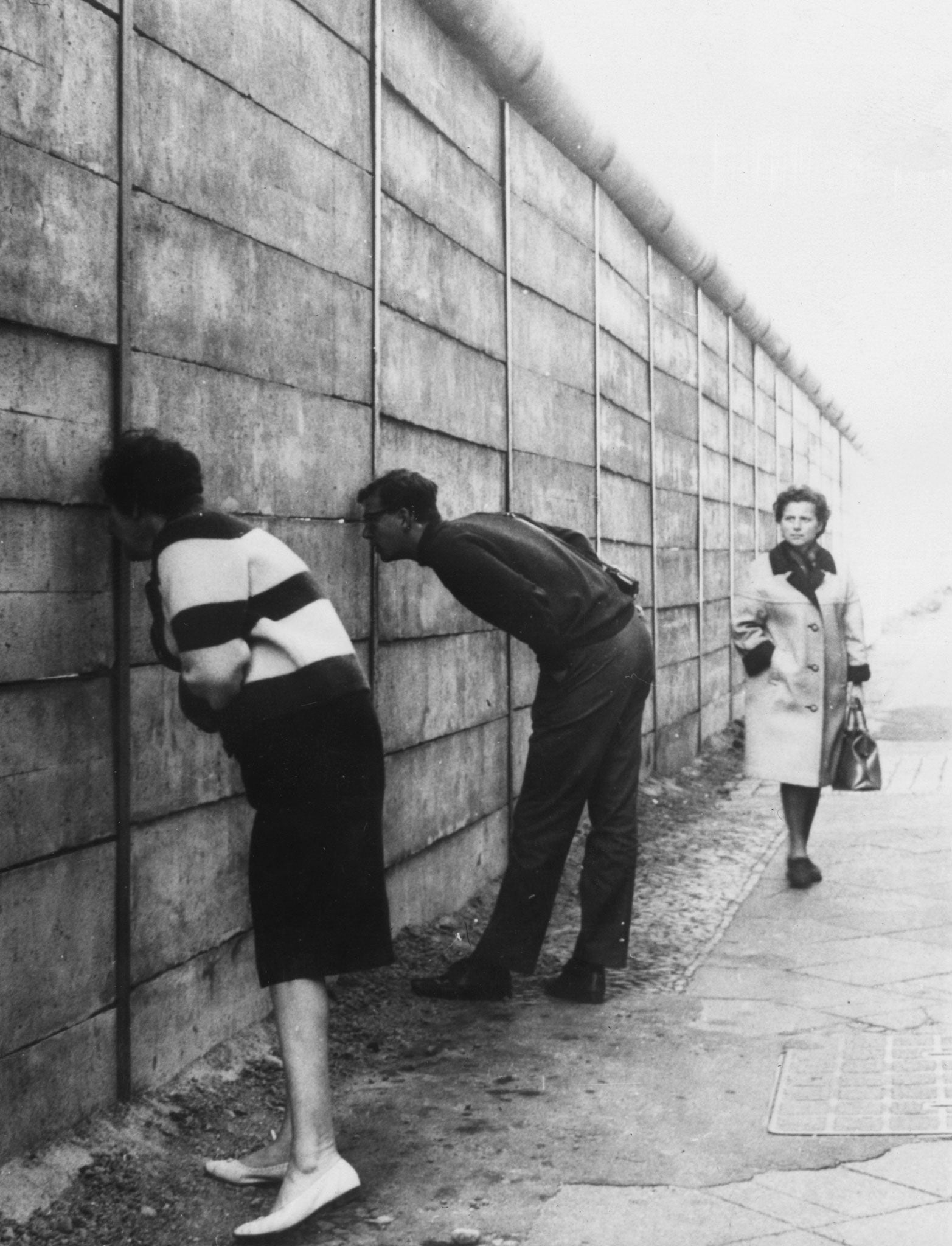

In 1961, he policed the Berlin Wall as it was being built. “We all thought that unlike the West, which still had former Nazis in power, that we in the East were building the better Germany,” he said.

He said he was overjoyed when the Berlin Wall went up because it “put an end to corruption and chaos” that was being caused by capitalist West Berlin. Of the scores shot dead at the Berlin Wall trying to escape, he says: “We always thought that any death at the Berlin Wall was one death too many, but we turned a blind eye to the fact that people were actually killed.”

Even after the Wall fell, like millions of East Germans, Harald Jäger still hoped that East Germany would reform its system and continue to co-exist with West Germany. “We didn’t believe in or even particularly want reunification,” he recalls.

It came less than a year later and Mr Jäger, who had by then transferred to the East German army, lost his job. After a few years, he scraped together enough cash to buy a newspaper kiosk just a few hundred yards from his former Bornholmer Strasse crossing point. “Some of the customers used to shout ‘don’t buy your papers from this Stasi pig’,” he recalls. “But most used to congratulate me for what I did,” he says.

Harald Jäger is now retired. But only recently has he been reaping the benefits of the freedom of travel he secured for his fellow citizens 25 years ago. Last month, he was in Liverpool, where he told his story to a packed audience at the city’s university. “I had a great time,” he says. For tomorrow’s anniversary he was interviewed by South Korean television. Mr Jäger is convinced that the North-South Korea divide will eventually go the same way as the Berlin Wall. “Sooner or later the Koreans – like the Germans – will find the way to each other,” he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments