How the European Union went from war baby to problem child

Beginning a three-part series, The Independent’s founding editor Andreas Whittam Smith heads toward his EU referendum decision by looking at the union’s post-war genesis – and why Britain has always been the odd one out

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Before we can decide whether to remain in the European Union or to leave it, it is important to understand what sort of thing it is. In doing this exercise, inevitably I find aspects that I don’t like, and perhaps many others will share my opinion. This means that in answering the referendum question, there is quite a difficult calculation to be made. We must think in terms of a bargain. On one side there is the price; on the other side, the benefit. We shall have to strike the balance.

Remembering that the characters of institutions, as well as of people, are generally set in their early years, I believe we should start at the very beginning. The EU in its original form was created by six nations (“the Six”) that had been at war with each other, the victors as well as the vanquished. These were France, which was overrun by the Germans in 1940 without putting up much of a fight; the Netherlands, Belgium and tiny Luxembourg – which were too small to resist the might of the German forces – and the aggressors themselves, Germany with Italy tagging along, both in their turn overwhelmed by British and American forces.

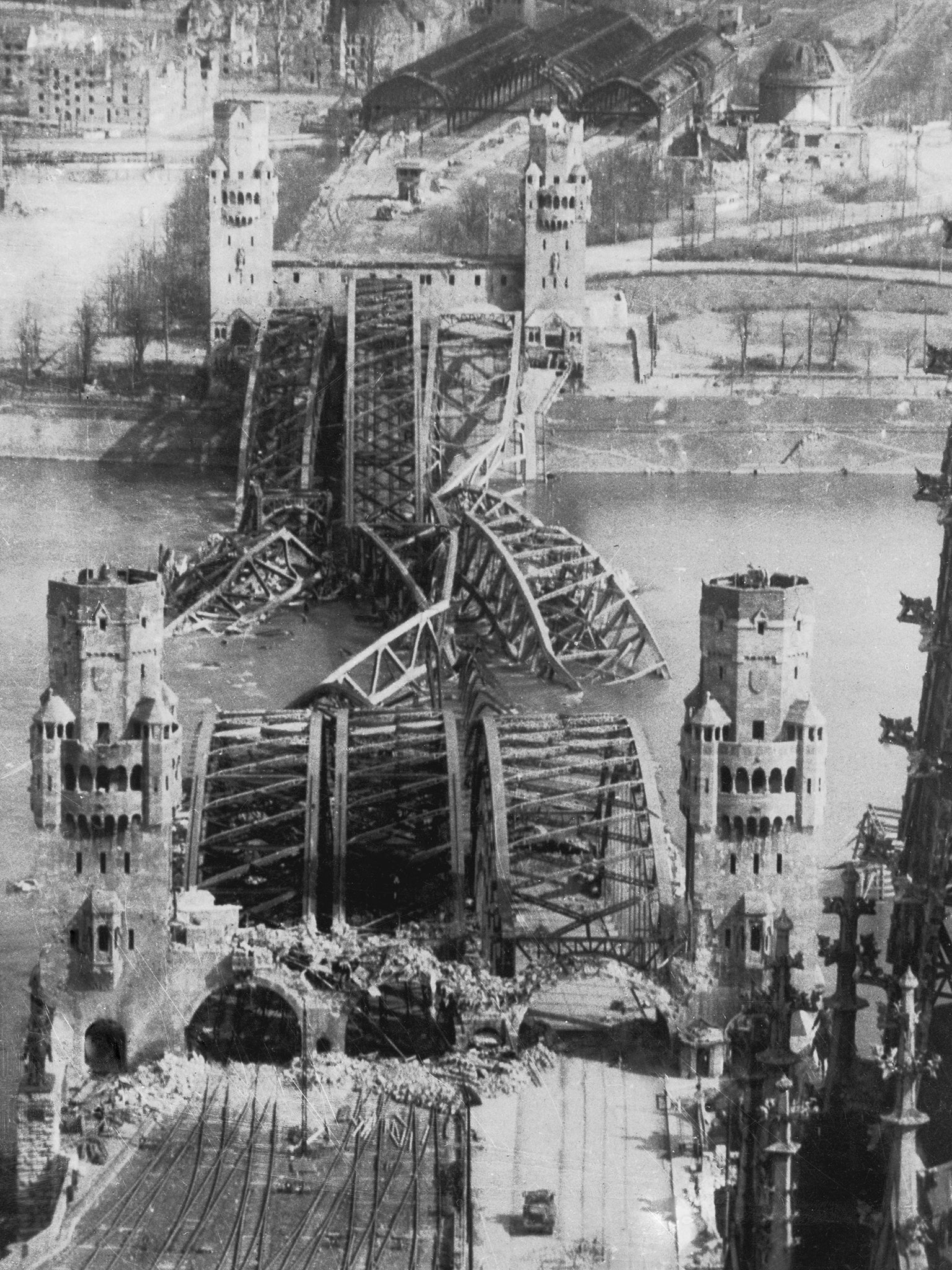

It is worth picturing in one’s mind what this meant. When the war ended in 1945, the destruction was as bad as anything we see today in television reports from Syria or Iraq. Günter Grass, the German novelist, who was 18 years old in 1945, has described the city of Cologne as a “pile of debris with an occasional miraculously surviving street sign stuck to what was left of a façade, or hung on a pole sticking out of the rubble, which was also sprouting lush patches of dandelions about to blossom”.

Britain also suffered devastating war damage but not the dispersal of families that Grass also recounts. He has written of the heart breaking efforts of families trying to find their missing children, or parents or other family members. “In towns and villages … the corridors of municipal buildings were hung with the names and dates of the missing and, often enough, of the dead … I, too, scoured the lists, posted weekly, for signs of my parents and my three-year old younger sister.”

Out of this experience there arose a widespread and understandable hatred for the governments that had led the countries of western Europe into such misery and chaos. Even worse, after the Nazi invasions, the governments in France, Norway, the Netherlands and Belgium had sometimes enthusiastically done the Germans’ bidding. A senior French lawyer, who remained in Paris throughout the war, recounted in his recently published diary, that in the Paris police headquarters, the equivalent of Scotland Yard, the French police constantly flattered their new masters and even gave them Nazi salutes.

Charles de Gaulle, the French general who escaped to London when the Germans arrived and was later to become president, put it clearly: “During the catastrophe, beneath the burden of defeat, a great change had occurred in men’s minds. To many, the disaster of 1940 seemed like a failure of the ruling class and system in every realm.”

In complete contrast, the British were proud of their wartime achievement. In June 1940, a month after he became prime minister, Winston Churchill had urged that we “therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that, if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, ‘This was their finest hour’“. After the war had ended, most British people felt that they had indeed met that challenge. Writer and broadcaster JB Priestley described on the BBC “how we began this war by snatching glory out of defeat, and then swept to victory”.

It wasn’t that the British were self-satisfied, as the general election held immediately after the war shows. For they expelled their great war leader, Churchill, and his Conservative Party from office and installed a Labour government with a big majority. But they had no sense of shame about the war itself or its causes. Nor had they lost faith in their political system. Indeed the newly elected Labour government was to create the welfare state.

The British were proud of their wartime achievements, in complete contrast their continental cousins

Because of this difference in attitude, which remains in the DNA of the countries of western Europe, any grouping that would contain Britain as well as the “Six” would perpetually have an odd-man-out – us. More important, the searing wartime experience that our continental neighbours went through explains why they have willingly, even enthusiastically, built a European Union that takes powers away from the despised nation states that they blame for the calamity.

In addition, and this has also been an enduring characteristic, the French remained terrified of German power. Even though Germany had been laid prostrate by Allied bombing and divided up into four zones of occupation, the French always had this question in front of the minds: how would France protect itself against a re-energised Germany? France’s first thoughts were punitive. General de Gaulle wanted the industrial plants of the defeated Germany dismantled and the country broken up into regional states – thus undoing the unification process of the 19th century.

But in the imagination of a French civil servant, Jean Monnet, now considered one of the founding fathers of the EU, a much more subtle and enterprising plan had been taking shape. There is a story told about him by his biographer, François Duchène:

“During the Second World War one morning in Algiers, a friend found Monnet deep in thought in front of a map of Europe laid out on his desk and striped with pencil lines. Showing the friend the regions of the Ruhr and Lorraine, he explained that all the trouble came from that part of the world. It was from their coal and steel that Germany and France forged the instruments of war. To stop another conflagration it would be necessary, one way or another, to extract this region from the two countries.” And this is in effect what France put forward in 1950, when a degree of stability had returned to western Europe. Nato had been set up the previous year.

The French foreign minister, Robert Schuman, proposed that all French and German coal and steel production be placed under a joint High Authority within a framework of an organisation which would also be open to the participation of the other countries of Europe. The historian, Alan Bullock, described the initiative as being “as bold and imaginative as any in European history”. Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg immediately agreed to join with France. These were the same six countries that seven years later signed the treaty that created the EEC, which in turn became the European Union.

This construction was called the European Coal and Steel Community, which sounds very dull. But with its High Authority, where capable public figures would take decisions binding on member states on the basis of the common interest, with its Assembly made up of nominated national parliamentarians, with its Council of Ministers and its Court of Justice and its assumption of legal powers, it was the template for all that followed. The High Authority was even obliged to promote the free movement of workers within the coal and steel industries.

Britain didn’t like this at all. The core difficulty was well illustrated by a question posed in the House of Commons by Rhys Davies, a trades unionist and Labour MP: “There are three-quarters of a million coal miners in this country who are now employed by the National Coal Board; who will be their employer if the Schuman Plan [for the creation of the single authority] comes to completion?” A very good point.

It went to the supranational nature of what was proposed. Some of the normal powers of a nation state would be transferred to a body that ranked above individual nations. The attraction to the makers of the EU was that it would not be buffeted by national politics. It would be on a different planet. But they failed to recognise how profoundly undemocratic this policy was – another characteristic that has lasted to the present day. The employment of Britain’s 750,000 miners would have escaped parliamentary control. We rejected the proposals.

There was also an addendum to the Schuman Plan to which little attention was paid at the time. It stated that the “new High Authority” would be “the first concrete step towards the federation of Europe”. Indeed the Six quickly got on with creating a precursor institution to the European Union, which was called the European Economic Community, or Common Market.

For amid the rubble, something miraculous had been taking place. Business activity on the Continent had quickly resumed. It turned out that much more plant and machinery had survived the German and the Allied bombing raids and the fighting on the ground than might have been expected. Only about a fifth of German industrial plant, for instance, had been destroyed.

Industrial production in Western Europe began to expand strongly. A study in The European Economy by historian Derek Aldcroft shows that by 1950-51 nearly all countries had increased their industrial output by a third or more above pre-war levels. Trade between the Six multiplied. As a result, European politicians and economists, who had been wondering since the war whether a “tariff union” between the Six would succeed, became enthusiastic. They argued that an area in which there were no trade restrictions between the member countries but whose industries were protected from outside competition by a sort of tariff wall would work remarkably well.

In 1955 negotiations between the Six – with a British observer present – began. But as these talks followed their formal agenda, something even more important was taking place in private. France and Germany had to do a deal. As Duchène observed of the negotiations: “Throughout, the French and Germans were preoccupied primarily with one another. The negotiations between the six community states were shadowed by a bilateral one between the Two, which surfaced at critical junctures.“

France decided to extract a price for opening up her markets, and so was born the noxious Common Agricultural Policy

Indeed I would say that France and Germany have been preoccupied primarily with one another since the first day and remain so today.

At issue were France’s concerns about meeting German competition within its home market without tariff protection. However, it was beginning to be argued within France that now was the time for French industry to meet German competition full on; it would be the better for having done so. And so, exhibiting enviable suppleness, France decided to extract a price for opening up her markets.

The price was that the common market arrangements should provide a good deal for French farmers. French leaders toured the countryside promising that “Europe” could offer farmers a protected outlet for meat, dairy products, grain and sugar beet. And so was born the noxious Common Agricultural Policy (the CAP) that was later to condemn British consumers to paying high prices for their food in order to subsidise French farmers.

The negotiations resulted in full agreement and the results were incorporated into a treaty between the six states, the Treaty of Rome. It is the foundational document of the European Union. The Treaty was signed in Rome on 25 March 1957 and became effective on 1 January 1958.

There would be a free-trade area between member states, surrounded by a tariff wall against competition from outside. The EEC would be based on the “four freedoms”, namely the free movement of persons, services, goods and capital. The treaty also established the governance of the Community. There would be a Council of Ministers of the member countries, with decision-making powers; a Commission with the executive power to make proposals to the Council of Ministers and to implement Community policies; a Parliamentary Assembly with an advisory role; and a Court of Justice to which national courts would submit cases for final adjudication.

To the Six, this seemed the best of worlds. The powers of the nation states would be limited by the supranational nature of the Community’s institutions. And there would be the bonus of belonging to a large free-trade area.

We stood aside. For a second time Britain refused to be present at the creation. Four years later, however, having seen how well the Common Market appeared to be working, we were knocking on the door. We then had to wait 13 long years, until 1973, before being admitted. In the interim, De Gaulle had twice vetoed our application.

On the first occasion, De Gaulle gave his reasons for rejection at a press conference. His words bear rereading: “The Treaty of Rome was concluded between six continental states, states which are, economically speaking, one may say, of the same nature. Indeed, whether it be a matter of their industrial or agricultural production, their external exchanges, their habits or their commercial clientele, their living or working conditions, there is between them much more resemblance than difference…

“England in effect is insular, she is maritime, she is linked through her exchanges, her markets, her supply lines to the most diverse and often the most distant countries; she pursues essentially industrial and commercial activities, and only slight agricultural ones. She has in all her doings very marked and very original habits and traditions.

Tomorrow I shall describe how Germany came to take over the leadership of the European Union from France, a Germany where, according to one expert, there is an increasing scepticism about – and even contempt for – Anglo Saxon ideas, whether about statecraft or about economics

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments