European Parliament Election 2014: A vote for Europe – or simply a chance to put the boot in?

Nearly 400 million people will have the right to vote in the EU polls - but many will see it as an opportunity for elite bashing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Roll up, roll up for the most bizarre election on the planet.

More than 380,000,000 people have the right to vote in the next few days in what is, theoretically, an important milestone on the road to a Europe-wide democracy. Less than half of them, however, will bother to do so.

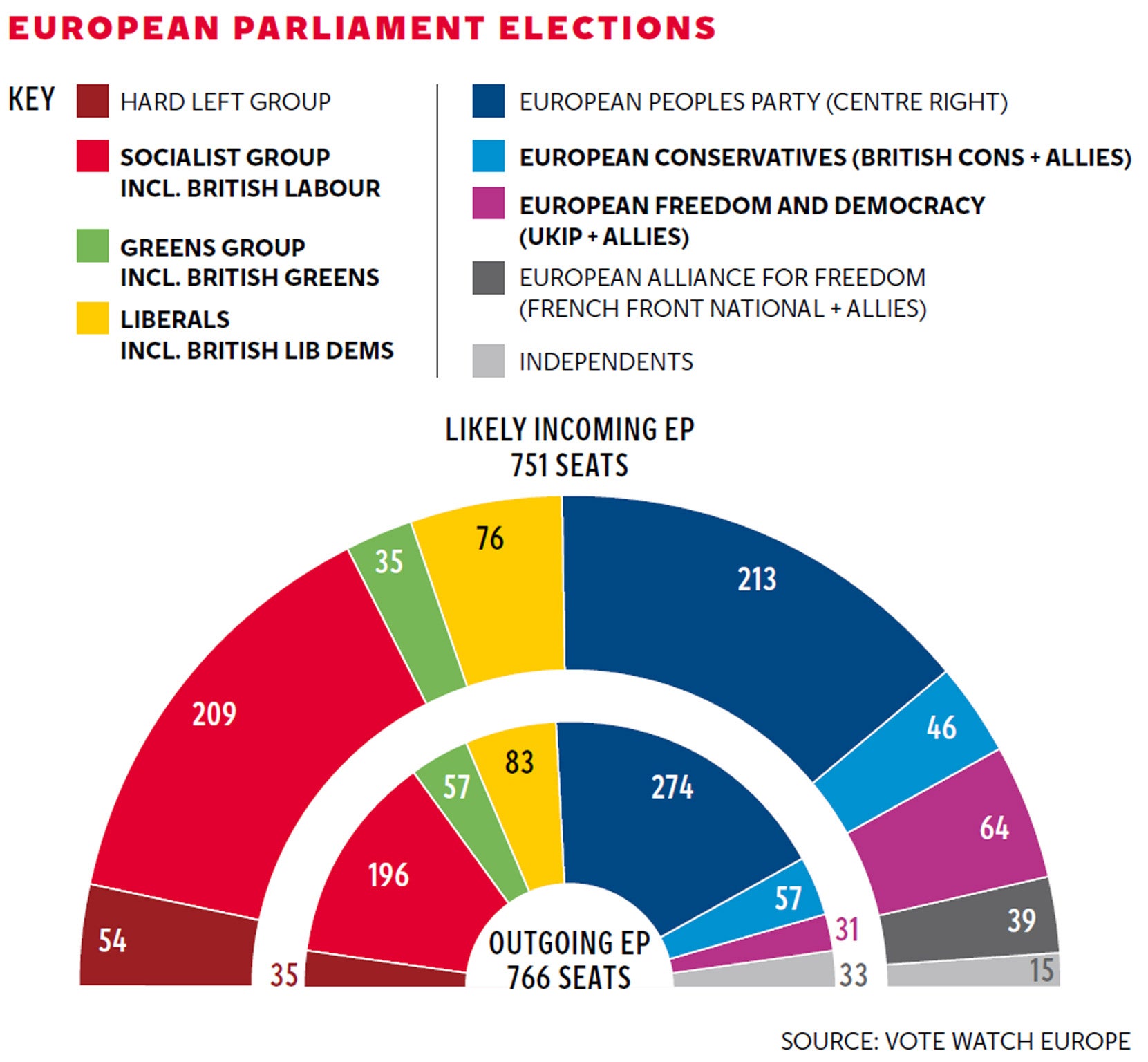

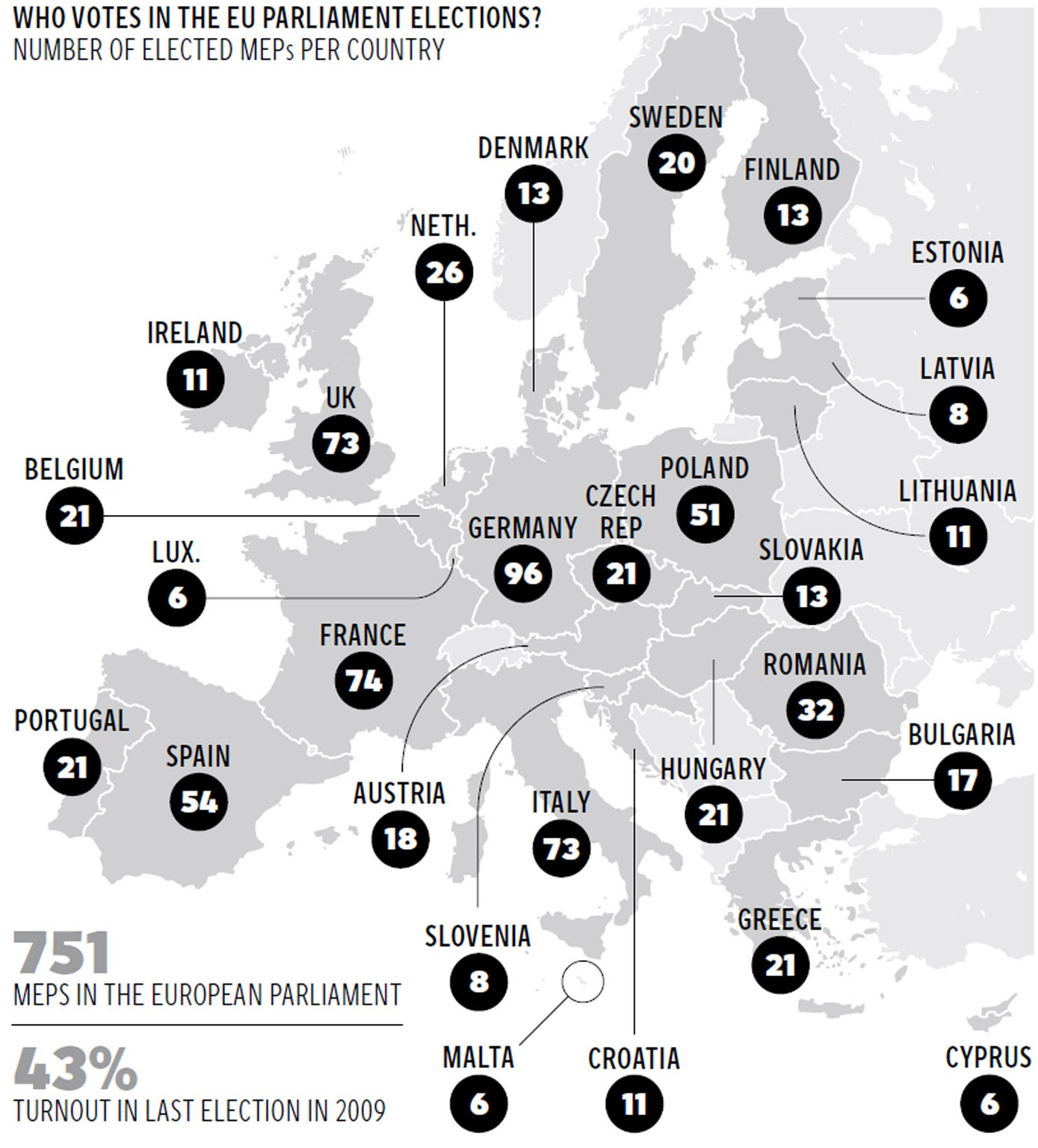

All the same – barring India – this will be the most gargantuan exercise in democracy ever attempted. Voting for 751 Euro MPs will take place in 28 countries over four days. And yet, it is those Europeans who detest the European Union, who appear most to cherish their right to vote this week.

Forget, for a moment, the predicted high Ukip vote in Britain. Eurosceptic, hard-nationalist parties are also threatening to top the poll, thanks to low turnouts, in at least two EU founding member states: France and the Netherlands. There will also be historically high Eurosceptic votes in Germany, Spain and Italy. One vote in three seems likely to go to parties of the hard right or the hard left, that loathe the EU in its present form – or in any form.

And yet, we are told, this is the first European election that will directly influence the high politics of Brussels. The outcome will, in theory, decide who replaces Jose Manuel Barroso as President of the European Commission at the end of this year.

After all the talk of a “democratic deficit” in Europe, of Brussels being “remote” and “faceless”, Europe’s voters have a chance to choose the personalities and policies that will shape the EU over the next five years. The great majority of them are scarcely aware that they have such a choice.

Martin Schulz or Jean-Claude Juncker? Guy Verhofstadt, Ska Keller or Alexis Tsipras? More than two-thirds of Europeans, according to one poll, do not know who these people are.

This will, in truth, be not one election but 29 – an election to the European Parliament that grips few voters; and 28 national, mid-term opinion polls, whose results will be skewed by the low turnout. National issues, in almost every case, will shape the outcome as much, or more than, European issues.

The European elections, precisely because they are non-national elections, are a wonderful, double opportunity for elite-bashing. They offer a chance to boot mainstream parties, without risking putting the populists in power. They offer a chance to boot the EU for its own sake.

There is a jumble of voting days and polling methods, Britain, the Netherlands and Croatia will vote tomorrow. Malta, Ireland and the Czech Republic on Friday and Saturday; Cyprus, Latvia and Slovakia on Friday; Italy on Saturday; and the rest on Sunday.

There are four different kinds of proportional representation, according to national taste. There are immense multi-seat regional constituencies in Britain, Poland, France, Italy and Belgium. In the other countries there is a nationwide poll with party lists of candidates.

When all the results are known on Sunday night, there will be no coherent EU-wide pattern. There will be a strong anti-European vote in countries that are doing well economically, such as Britain, Austria and Finland. There will be an overwhelming vote for pro-European parties in some of the countries that have suffered most in the Euro crisis (Ireland and Portugal) but a strong anti-Brussels backlash in others (Greece, Italy and Spain).

In some countries (Britain, Germany, Finland, Denmark), the EU will be attacked as a bureaucratic intrusion into free enterprise and global trade. In others (France and Italy), it will be lampooned, by both hard right and hard left, as a conspiracy by ultra-liberal, Anglo-Saxon, market fundamentalists to enslave the ordinary people and destroy national identity. Only one anti-EU theme is constant from Britain to Hungary, Germany to Greece – that Brussels is responsible for unwelcome levels of immigration, both within the EU and from the outside.

The elections will not paint a flattering picture of the EU. Sixty six years after the creation of the Common Market, 100 years after the start of a Great European Civil War, it will emerge as, at worst, detested and, at best, misunderstood and unloved.

Many will interpret the results as proof that the Union is doomed. They could just as easily be offered as proof that the EU is indispensable (but needs radical overhaul). Consider what might happen to the European free market alone if there was no EU treaties to restrain all those jarring national differences.

In France, Marine Le Pen’s anti-immigrant, anti-market, anti-American party, Front National (FN), hopes to emerge this weekend as the leader of Anti-Europe. The FN may win as many as 20 of the 74 French seats – even though it only has two seats in the French national parliament.

Ms Le Pen is in a partnership, called “the European Alliance for Freedom” (EAF), with the Geert Wilders’ anti-immigrant party, the PVV, in the Netherlands; with the “True Finns”; and with the hard right Austrian freedom party, the FPO. With other odds and ends, she should comfortably win the 25 seats from seven countries that she needs to form a parliamentary group in Strasbourg.

Nigel Farage and Ukip have refused to throw in their lot with Ms Le Pen. To her fury, he insists that the French FN remains racist and anti-semitic in its “DNA”. Ms Le Pen retorts that he is jealous of her attempts to create a hard European right under her leadership. All the same, Ukip should be able to greatly expand its existing “Europe of Freedom and Democracy” group, mostly with right-wing nationalist, eastern European parties. Some of the wilder, neo-Nazi fringes of the European hard right – Jobbik from Hungary and Golden Dawn in Greece – will win a clutch of seats but will be excluded from both these groups. The British Conservatives, with a ragbag of allies, will probably hold on to their separate mildly anti-European group, the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR).

If you add a steep increase in hard left seats, more than one in three members of the new European Parliament will fervently wish that the institution did not exist. That is bizarre. But what will it mean?

Under the Treaty of Lisbon, the parliament is far more than a talking shop. It has done much to clean up its act. It has power to propose and amend European legislation.

It remains an odd beast – impressive as the only supranational, democratic institution in the world; ignored because it lacks the aura and legitimacy of popular understanding or interest.

Ms Le Pen says that she hopes to have a “blocking minority” to prevent any further legislation which dilutes national sovereignty. In practise, no such blocking minority exists in the parliament’s rules. The anti-Europeans will be heavily outnumbered by the “pro-Europeans” of the centre-right (European People’s Party), Socialists, Liberals and Greens.

The disparate “antis”, from the neo-Nazis to the Tories, will still find many opportunities for sabotage. Whether they will be able to work together to exploit those opportunities is open to question. One area in which they could be influential – and might paradoxically please many of the member states – is in the choice of the next President of the European Commission.

The rules are ambiguous. Member states select the candidate but that the parliament endorses or reject the governments’ nominee. According to the Treaty of Lisbon, the results of this week’s elections must be “taken into account”.

The parliament’s leaders insist that this means that each political group has the right to present a candidate for Commission president in this week’s election. The champion of the group which wins the most seats should, they say, be endorsed by the member states as the next head of the Brussels executive.

This implies a straight fight between the centre-right candidate, Jean-Claude Juncker (former Prime Minister of Luxembourg) and the Socialist candidate, and Parliament president, Martin Schulz, from Germany.

The other candidates mentioned earlier, represent the Liberals, Greens and hard left. These groups have no realistic chance of coming first this weekend. Polls suggest that Mr Juncker’s EPP should narrowly pip the Socialists with just over 200 seats each.

Most of the big member states reject this interpretation of the treaty. They insist that they are free to cast their net more widely. The parliament threatens to reject any nominee who did not run in the European elections.

The scene is set for a stonking Euro-row, in which the anti-European third of the new assembly could easily play a significant and mischievous role, delaying a decision indefinitely.

This may seem a sterile debate but it goes to the heart of one of the great conundrums in European politics. There can be no real, direct democracy in Europe until European citzens think in European terms. Voters will not think in European terms until there is Europe-wide democracy. This weeks’ election was supposed to start, timidly, to resolve that conundrum. It is likely to leave it as impenetrable as ever.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments