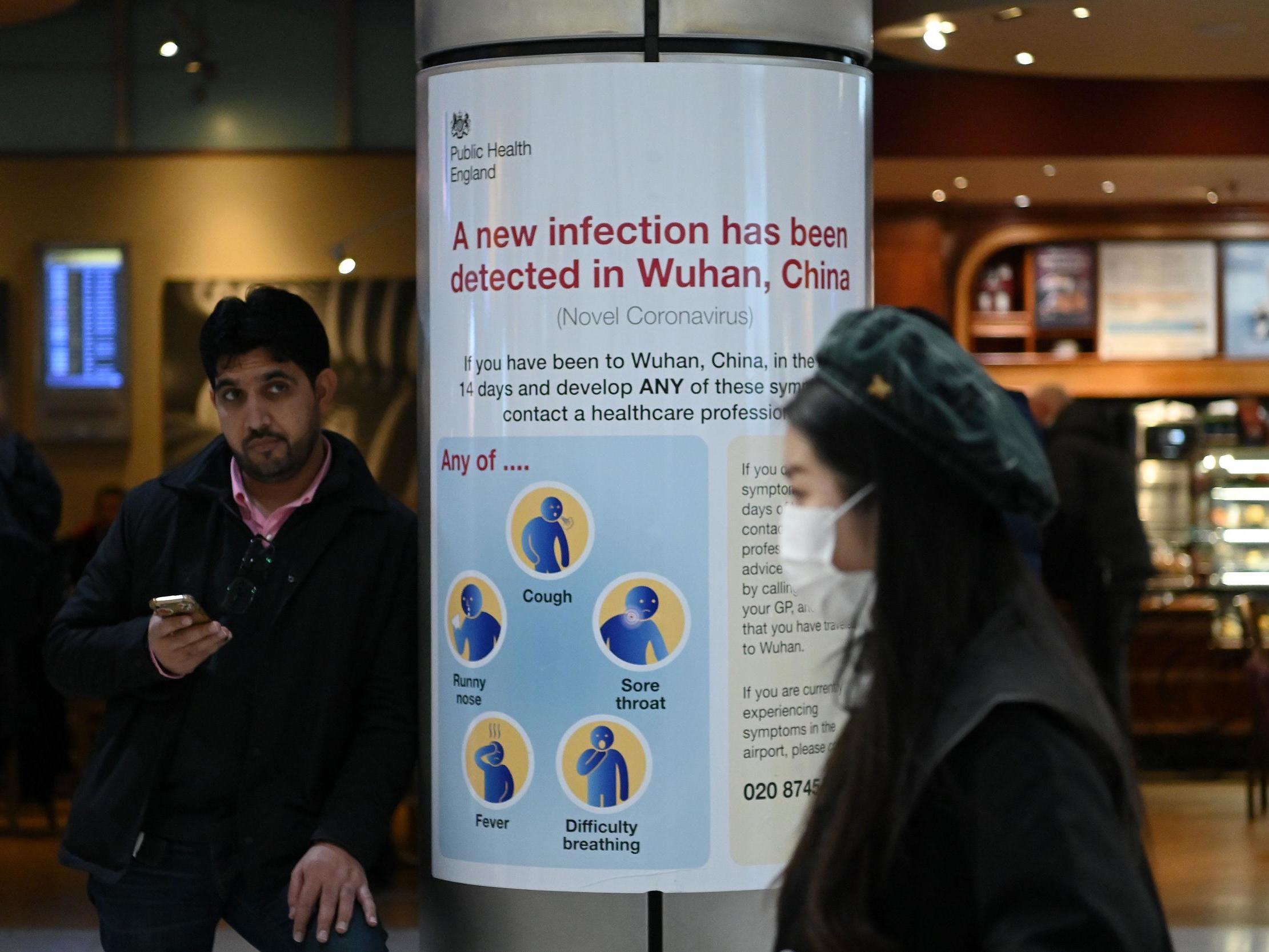

Coronavirus: Europe’s open borders threatened by spread of disease

As cases spread and multiply, calls for closing borders have grown louder — most predictably from nationalist politicians

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For Europe, the coronavirus could not have arrived at a worse time.

This was the year — with Britain out, terrorism waning and the migrant crisis at an ebb — that the European Union had hoped to repair and revive its cherished goal of open internal borders.

But cases of the virus have emerged nearly daily in new European countries — in Spain, Greece, Croatia, France, Switzerland and, on Wednesday, in Germany. Many of them can be traced back to Europe’s largest outbreak, in Italy, where more than 300 people are now infected.

As the cases spread and multiply, calls for closing borders have grown louder, most predictably from the far-right and populists who were never fans of the bloc’s open border policy.

So far no country has taken that drastic step, but privately European officials warned that this could change quickly. On Wednesday, the bloc’s top official for communicable diseases said that Europe needed to prepare more broadly for the kind of crisis that has hit northern Italy.

“Our current assessment is that we will likely see a similar situation in other countries in Europe, and that the picture may vary from country to country,” said the official, Andrea Ammon, director of the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control.

“We also need to consider the need to prepare for other scenarios — for example, large clusters elsewhere in Europe,” she added, speaking at a news conference in Rome.

While she urged far greater coordination among European Union members, she stopped well short of recommending that they start shutting their borders.

Other health experts argued that such a step would be of dubious benefit in any case.

“Travel restrictions don’t work: People find another way around it; it might only slow the virus down,” said Dr Clare Wenham, of the London School of Economics Global Health Initiative.

The free movement of people and goods is a cornerstone of the European Union, referred to by the shorthand “Schengen,” after the city in Luxembourg where the 1985 treaty that created what is now a 26-nation, passport-free zone was signed.

Europeans consider it one of the bloc’s biggest achievements. But if it has nurtured prosperity and become a fundamental building block of European identity, it has also, practically speaking, been suffering a death by a thousand cuts.

The latest came in 2015, when a number of countries suspended Schengen to allow full control over their borders and stop refugees who had landed in Greece and elsewhere from making their way to the wealthier European north.

The rules allow for the temporary reintroduction of border checks for specific reasons, including terrorist attacks, major migrant surges or health emergencies.

The key, though, is the word “temporary.” A country can suspend the rules, but it needs to explain why it’s doing it, and in theory it can’t carry out border controls for longer than two years, according to existing rules.

In what experts argue is an abuse of the rules, Germany, France, Sweden, Denmark, Austria and Norway have practically scrapped Schengen and have been checking passports of travellers arriving from other member states for the past 4 1/2 years, using legal manoeuvres to circumvent the two-year limit.

“Schengen is in a very poor and problematic state,” said Marie De Somer, head of the migration program at Brussels-based think tank European Policy Centre, adding that restoring it to its full functionality hinges on changing the bloc’s asylum and migration rules.

The virus is yet another challenge, as it has given new ammunition to nationalists who want to see borders tightened or restored even before the contagion arrived.

Eric Ciotti, a French parliamentarian from the region bordering Italy and a member of the right-wing Republican party, called for reinforced border controls “before it is too late.”

Marine Le Pen, leader of the far-right National Rally, weighed in, also calling for border closures with Italy.

And in Switzerland, which isn’t an EU member but does participate in the border-free area, Lorenzo Quadri of the right-wing Lega dei Ticinesi called for a “closed-doors” policy.

“It is alarming that the dogma of wide-open borders is considered a priority,” he said.

Long before the virus, many nationalists, led by Hungary’s prime minister, Viktor Orban, had complained that Europe could not have open internal borders if its outer borders were weak, allowing asylum-seekers to enter unchecked.

The European Commission was trying to put together a plan to fix Europe’s asylum system, including bolstering Frontex, the EU border agency, by adding staff and funding and stepping up its operations at the bloc’s external borders.

But the plan is facing resistance because it also aims to create a system for distributing asylum-seekers, something Hungary is likely to veto.

The divisions over the policy are manifold. Germany wants all countries to take refugees whether they like it or not. Greece wants asylum-seekers quickly taken out of its detention centres. Italy doesn’t want rescue boats to take refugees to its ports. The list of complaints goes on.

Professor De Somer said that it’s impossible to know the true effect of the suspension because Germany and the other countries that have reintroduced border controls have shared little information on how they’re using these checks and with what outcomes.

“We have very few figures on how the suspension of Schengen affects people, and it’s likely there’s not much to show for it. That tells us this is about symbolism rather than about practical issues: It’s about politics rather than policy,” she said.

European officials working on a migration overhaul that will affect borderless travel say that the virus is at the very least a setback for their efforts, as it offers populists another opportunity to underline the importance of national border controls. The virus, some officials said, could offer a reason to kick the can down the road, avoiding a thorny subject bound to cause division.

Professor De Somer, of the European Policy Center, is more optimistic. She thinks that even if border checks are reintroduced because of the virus, it could be an opportunity to show that Schengen is flexible and can work to protect citizens.

“If health experts and the commission recommend this, then it would show the system actually can function even in a crisis,” she said.

The catch?

“The checks would need to be lifted according to the rules, when the threat from the virus goes away.”

The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments