Atlantropa: One man's colossal answer to Europe's post-WWI refugee crisis

As the continent struggled, a German architect turned to Africa for inspiration

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Perpetual war, grinding poverty and a time bomb of overpopulation resulting in millions of refugees crossing continents. A fitting description perhaps for the emergency facing Europe today – but those problems also fuelled a German architect’s extraordinary 1920s scheme to resettle millions of Europeans in Africa.

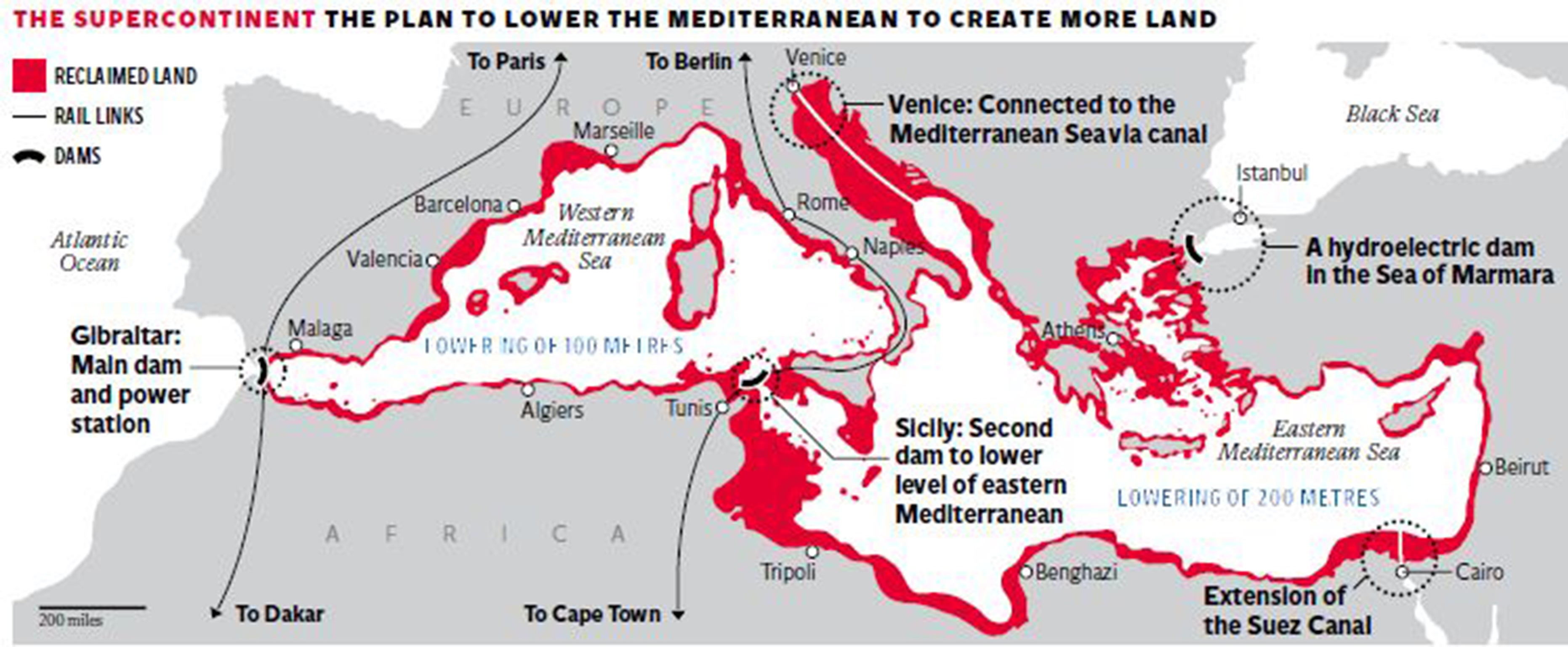

The “Atlantropa” scheme proposed to form land bridges between Africa and Europe by damming and partially draining the Mediterranean, allowing millions of Europeans to find a new life in what would become the southern zone of a Eurafrican supercontinent. It would, of course, lead to European domination of Africa – a fact deemed acceptable in an era scarred by racism and colonialism.

The plan was the result of Herman Sörgel’s experience of the First World War, the economic and political turmoil of the 1920s and the rise of Nazism in Germany. It convinced him a new world war could only be avoided if a radical solution was found to European problems of unemployment, overpopulation and an impending energy crisis.

With little faith in politics, Mr Sörgel turned to technology. He tirelessly promoted Atlantropa through the Second World War and beyond, until his death in 1952.

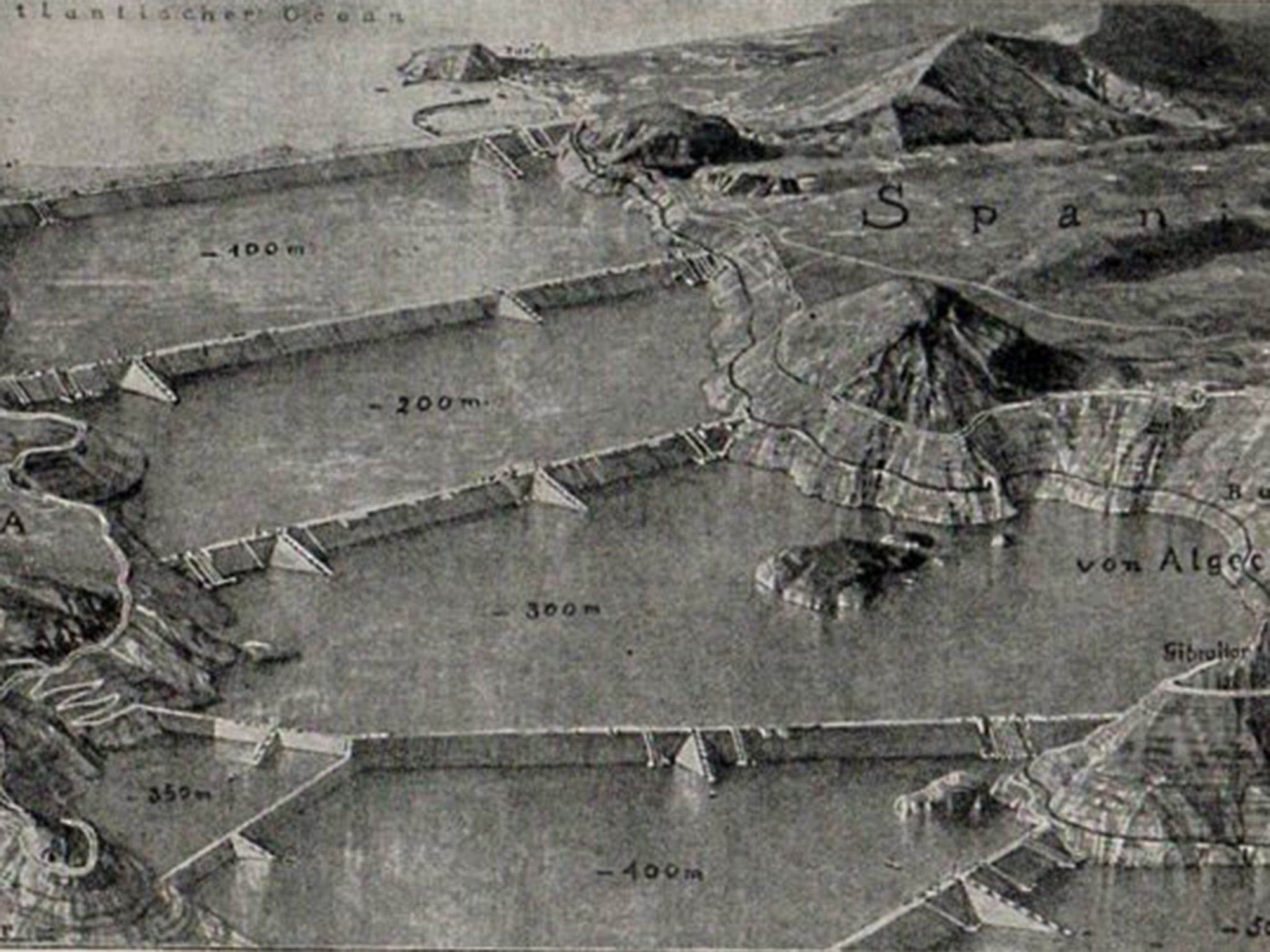

Dams across the Strait of Gibraltar, the Dardanelles, and eventually between Sicily and Tunisia, each containing gigantic hydroelectric power plants, would form the basis for the new supercontinent. In its final state the Mediterranean would be converted into two basins, the western part lowered by 100 metres and the eastern part by 200 metres and an area larger than France reclaimed from the sea.

Later plans for Atlantropa also included two dams across the Congo River and the creation of a Chad and Congo Sea, which Mr Sörgel hoped would have a moderating influence on the African climate, making it more pleasant for European settlers.

In line with the colonial and racist attitudes of the times, Mr Sörgel envisaged Africa to be entirely at the disposal of Europe, a continent with plenty of space to accommodate Europe’s masses.

While his proposal may sound absurd to our ears, it was taken seriously by architects, engineers, politicians and journalists at the time. The extensive Atlantropa archive in the Deutsche Museum in Munich abounds with architectural drawings for new cities, the dams and bridges of the future continent as well as letters of support and hundreds of articles about the project, which appeared in the German and international popular press, as well as in specialised engineering and geographical magazines.

What made Atlantropa so attractive was its vision of world peace achieved not through politics and diplomacy, but with a simple technological solution.

Atlantropa would be held together by a vast energy net, which would extend from the gigantic hydroelectric plant in the Gibraltar dam and provide the entirety of Europe and Africa with electricity. An independent body would have the power to switch off the energy supply to any country that posed a threat to peace.

Moreover, Mr Sörgel calculated the construction of the supercontinent would require each country to invest so much money that none would have sufficient resources to finance a war. He dedicated a large part of his work to the promotion and dissemination of the project through the press, radio, films, talks, exhibitions and even poetry and an Atlantropa symphony.

His grand scheme never came to pass, but the European Union almost 100 years later is dealing with Mr Sörgel’s envisioned disaster in reverse. What solution it finds will perhaps shape the next 100 years of the continent.

Ricarda Vidal, Lecturer in Visual Culture and Cultural History, King's College London

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments