Anschluss and Austria's guilty conscience

Seventy years after the Nazis' annexation of Austria, questions remain over whether its citizens were victims or accomplices

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The black and white photo was taken in Vienna 70 years ago this week: it shows a crowd of ordinary Austrians and a handful of officials sporting swastika armbands. All of them are grinning or smirking. At their feet six raggedly clad Jews are on their knees, being forced to clean the pavement with brushes.

The picture is a snapshot of the instant "people's justice" meted out by Aryan Austrians against the perceived enemies of the Third Reich. It was taken only hours after 105,000 Nazi storm troopers, many of them singing, marched into the country on 12 March 1938 and formally declared political union or "Anschluss" with Germany.

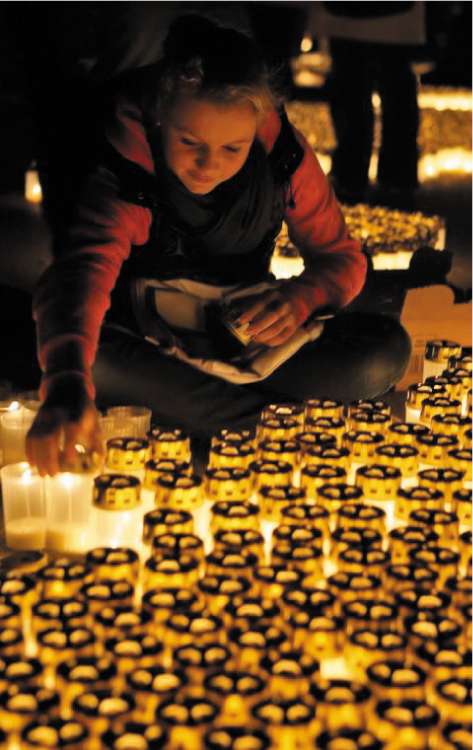

Last night, 80,000 candles were lit on Vienna's Heldenplatz square to mark the 70th anniversary of the darkest chapter in Austrian history. The candles represented the total number of Austrian Jews and other victims who lost their lives as a result of Nazi rule.

In March 1938, tens of thousands of Austrians gathered in the square to welcome home Adolf Hitler, who was born in Austria, like a prodigal son. In deliberate contrast to that loud enthusiasm, yesterday's sombre ceremony was called "The Night of Silence".

Despite open displays of remorse about the Nazi era, the 70th anniversary of Austria's annexation has inevitably revived a long-running debate about whether its citizens were victims or willing accomplices of the Third Reich.

Public reluctance to confront the issue was underscored this week by Otto von Habsburg, the 95-year-old son of the country's last emperor. He told a meeting of the ruling conservative People's Party: "No state in Europe has a greater right than Austria to call itself a victim." He went on to dismiss an Allied wartime declaration that Austria shared responsibility for the Nazis as "hypocrisy and lies". The thousands who greeted Hitler were just like "high-spirited football fans", he insisted.

His remarks followed publication of an opinion poll on Tuesday which showed that almost two thirds of Austrians wanted an end to what was described as the "endless discussion" about the country's role during the Second World War. (The result of a similar poll conducted eight years ago was the same).

However, new evidence and a growing mass of research about Austria's role during the Third Reich suggests that the argument that the vast majority of its citizens were willing accomplices to Nazi rule has become incontrovertible.

Less than a month after German troops marched into Austria, Hitler ordered that the invasion be ratified by plebiscite. The poll conducted on 10 April 1938 showed that 99.75 per cent of Austrians were in favour of the annexation. Subsequent claims that the results were doctored by the Nazis were later substantiated. But recent research suggests that the actual number in favour of Nazi rule was still about two thirds of the electorate.

Professor Gerhard Botz, a historian at Vienna University who has researched the period closely, said yesterday: "Hitler was welcomed into the country as a successful Austrian who was returning home from abroad and suddenly letting his own people take part in his successes. He was a sort of ersatz monarch."

Gershon Evan, an Austrian Jew whose parents were arrested and killed by the Nazis, recalled during a television broadcast yesterday how quickly racial persecution took hold in Vienna, a city in which every 10th citizen was then Jewish. "What happened in Germany over five years, happened in Vienna in five days," he said. "We had no idea that we would face such violence."

Austria's Jewish community numbered some 200,000 before the Second World War and was considered one of Europe's most vibrant. Most, like Mr Evan, managed to flee the country after the Anschluss, but 65,000 were murdered in the Nazi death camps. New research has shown that the number of Austrians who held key positions in Nazi concentration camps was disproportionately high. Today, Austria is home to 10,000 Jews.

Film footage of the jubilant reception given to Hitler in Vienna has frequently been dismissed in Austria as stage-managed Nazi propaganda. "This kind of argument is used by the Austrians who claim that they are innocent and the Nazis were the invaders," said the Viennese author and historian Brigitte Hamann.

However, new independent film material about the period was shown for the first time in Germany this week. The colour footage, shown on Germany's ZDF channel, was taken from 90 minutes of film shot by an Austrian forester called Marilius Mayer in March 1938. The film shows images of a provincial town in which the locals have turned out en masse to demonstrate their support for the invading Nazis. The streets are hung with hundreds of red, black and white swastika banners and the town square has been hastily renamed "Adolf Hitler Platz".

Earlier this week a poignant ceremony was conducted by Vienna's now tiny Jewish community to mark the anniversary. Seventy years after it was forcibly shut down and taken over by the invading Nazis, members gathered to reopen the Hakoah sports club – an institution that once produced Olympic champions for Austria.

The club was evidence enough of the prevailing attitudes in 1930s Austria before it was shut down. It existed because the overwhelming majority of the city's other sporting organisations refused to accept Jews as members. Hakoah, founded in 1909 and named after the Hebrew word for "strength", produced athletes who won Olympic medals in swimming and wrestling.

After the Second World War, Vienna's surviving Jews refounded the club but their attempts to return to their former premises were thwarted by bureaucracy and official reluctance to acknowledge Austria's Nazi role or pay compensation. The club finally secured a site close to its original premises in 2002 under a £100m reparations settlement for Jewish victims of Nazi rule.

Ronald Gelbard, the manager of the reopened Hakoah club, insisted that Austria's non-Jews were welcome. "We are a Jewish organisation but anyone can use the facilities regardless of faith," he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments