Anne Frank at 90: How the teenager’s diary captured the reality of life under Nazi occupation

Jewish schoolgirl’s daily journal, written from her family’s secret annexe in Amsterdam during Second World War, captures young author’s bursting ambition as well as tense realities of life in confinement

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Anne Frank, the Jewish schoolgirl whose diaries of her time in hiding during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands stand as one of the most significant documents to arise from the Holocaust, would have celebrated her 90th birthday on 12 June.

The Frank family had relocated to Amsterdam in 1934 to escape rising antisemitism in their native Frankfurt, part of a mass exodus that saw some 300,000 Jews flee Adolf Hitler’s Germany between 1933 and 1939.

Settling in an apartment on Merwedeplein in the neighbourhood of Rivierenbuurt, Otto and Edith Frank and their daughters Margot and Anne adjusted to their new surroundings relatively comfortably at first.

Otto Frank supported his family by working for Opteka Works, a company which produced a gelling agent used for making jam, before starting a second business known as Pectacon selling herbs, pickling salts and spices. Anne attended a Montessori school, learned Dutch and easily made friends, demonstrating a particular aptitude for reading and writing.

Following the outbreak of the Second World War, Hitler’s Germany took the Netherlands on 15 May 1940, the occupying government moving quickly to introduce the same prejudicial laws the Franks had already been subjected to in Frankfurt, including mandatory registration and public segregation. Jews were barred from public transport, parks, cinemas and non-Jewish shops and made to wear a Star of David to identify themselves.

When the state attempted to confiscate Otto’s businesses, he transferred his shares to a gentile friend, Johannes Kleiman, and resigned as director. Another friend, Jan Gies, assumed control of assets belonging to Opteka and Pectacon, allowing Otto’s interests to survive.

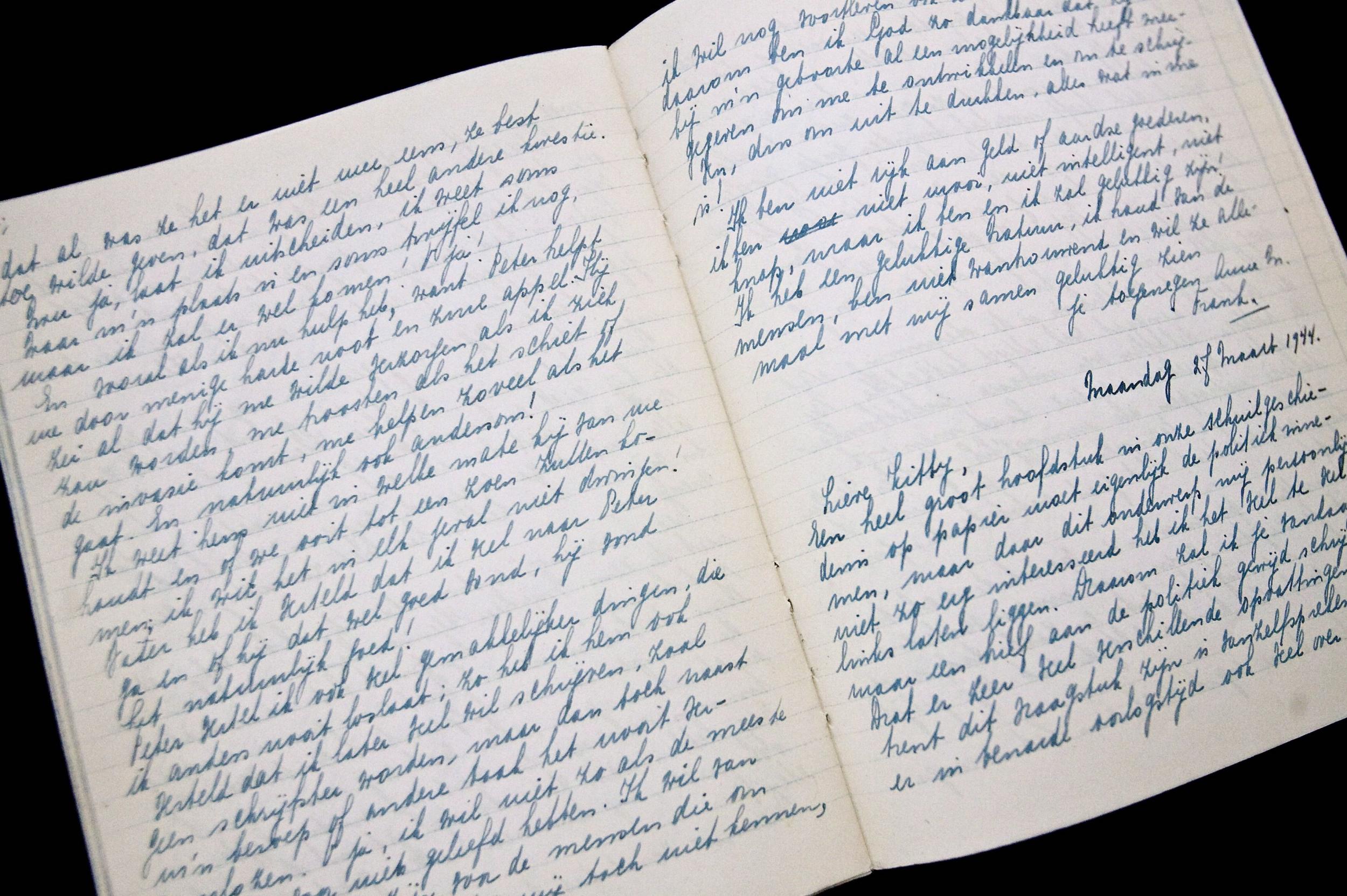

Margot and Anne had meanwhile been removed from their respective schools and sent to the Jewish Lyceum. Unnerved but undeterred, Anne celebrated her 13th birthday and received a red-and-white plaid autograph book, an item she planned to use as a diary to record her thoughts and feelings.

A month later, Margot received a letter from the Central Office for Jewish Emigration ordering her to report to a labour camp.

On 6 July 1942, Otto Frank moved the family into a secret annexe he had furnished at the rear of his workplace on Prinsengracht with a view to using it as an emergency hiding place. They were soon joined in their three-floor hideaway, its entrance concealed behind a bookcase, by Hermann, Auguste and Peter van Pels and then in November by Fritz Pfeffer, a dentist and friend of the family.

Klieman and Gies would again come to the family’s aid, the pair part of a trusted circle who knew the truth about the Franks’ sudden disappearance that also included Jan’s wife Miep, Johan Voskuijl, the latter’s daughter Bep and Victor Kugler, employees of the firm. This collective would support the Franks, Van Pels and Pfeffer throughout their confinement, supplying them with food and news of the war.

Until the Gestapo stormed the annexe on 4 August 1944, arresting the occupants, jailing their assistants and dispatching the Frank family to Auschwitz-Birkenau, Anne found solace in her diary.

In addressing the journal directly as “Dear Kitty”, as though composing a letter, Anne was actually imagining writing to Kitty Francken, a fictional character recurring in Cissy van Marxveldt’s popular series of Joop ter Heul books for young girls that appeared between 1919 and 1925.

In it, she recorded her most intimate thoughts and feelings. “I feel bad for lying in a warm bed, while my dearest friends are out there somewhere, thrown or fallen to the ground. And that only because they are Jews,” she wrote on 19 November 1942.

She recounted her tensions with her roommate, Pfeffer, with whom she fought for access to their shared writing desk, the older man wanting it for his study of foreign languages. “Stay calm, this fellow isn’t worth worrying your head about!” Anne wrote in exasperation on 13 July 1943, later detailing his petulant refusal to speak to her for two days or sit with her at dinner after a falling out.

Anne had covered the bare walls of their room with photographs of Hollywood movie stars and royalty clipped from magazines like Libelle. Those pictures of women like Norma Shearer, Greta Garbo and the princesses Elizabeth and Margaret offer a glimpse of the dreamworld in which she lived and her teenage fantasies of how her life might turn out after the war was won.

Just last year, we learned something new about her developing sexuality during the period when the Anne Frank House used new digital scanning technology to read behind the brown paper she had pasted over entries she was embarrassed by. The secret passages found Anne musing on the mechanics of sex, contraception, menstruation and prostitution.

Anne was also an astute observer of everything that went on as cabin fever set in between her family and the Van Pels: “Daddy goes about with his lips tightly pursed, when anyone speaks to him, he looks up startled, as is he is afraid he will have to patch up some tricky relationship again... Quite honestly, I sometimes forget who we are quarrelling with and with whom we’ve made it up.”

Anne often feuded with her mother during their two years cooped up together, Edith more inclined towards despair than her daughter. The Van Pels also fought while Margot was more withdrawn, quietly keeping a diary of her own.

When she heard a Radio Oranje broadcast from the Dutch government in exile in London appealing for citizens to keep hold of their records of the war, Anne was inspired to rewrite her journal entries into a consistent narrative, calling it Het Achterhuis (The Secret Annexe).

She later reflected on the importance of committing her inner life to paper, writing on 5 April 1944: “No one who doesn’t write can know how fine it is. And if I don’t have the talent to write for newspapers or books, well then I can always go on writing for myself.”

Anne Frank would no doubt have been both delighted and stunned to learn of the publishing sensation her diary would become after it was salvaged by Miep Gies and Bep Voskuijl following her death from typhus at Bergen-Belsen in February 1945, aged just 15.

Her father was the only member of the family to survive the Holocaust and only came to read his youngest daughter’s prodigious output in the aftermath of the Allied victory, deeply moved by the realisation of how integral it had been to her endurance.

Otto Frank ensured The Diary of a Young Girl reached publication in 1947 – it would be read around the world and translated into 70 languages – but returned to Amsterdam only to marry a fellow survivor, Elfriede Geiringer, living the rest of his life in Basel, Switzerland. Staying on was just too painful.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments