Agent provocateur: Inside the secret archives of East Germany's secret police

Simon Menner spent three years trawling through millions of surveillance images in the archives of the East German secret police. What he found was often laughable. But, he tells Holly Williams, beneath the Austin Powers exterior, there was evidence of a truly disturbing machine that still has the power to break its subjects

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.While the recent leaking of government-surveillance information hasn't exactly been welcomed by the secret services behind it, an exception comes in the form of the documents obtained by the spies of the Stasi, the Ministry for State Security run by the former German Democratic Republic (GDR).

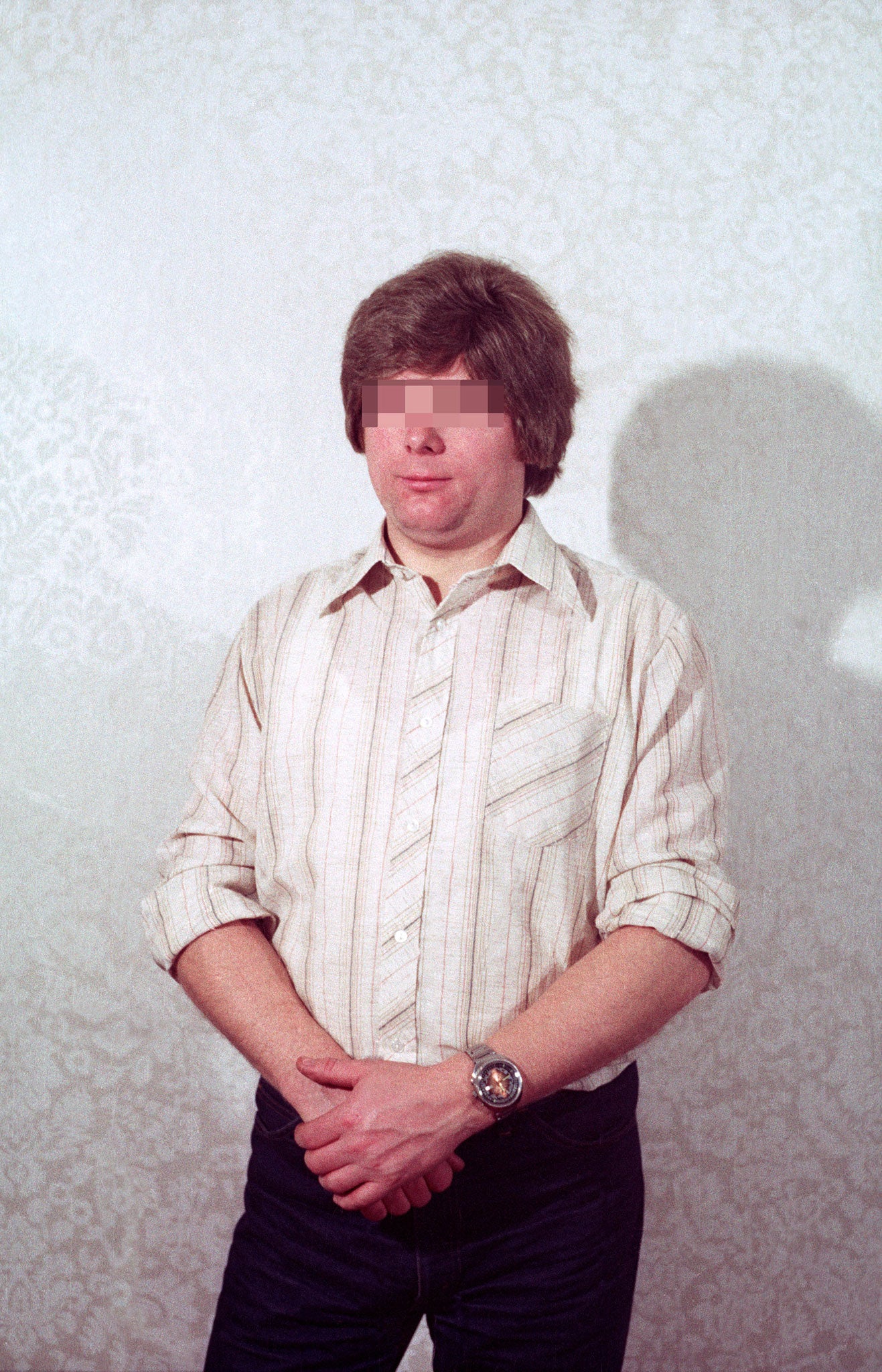

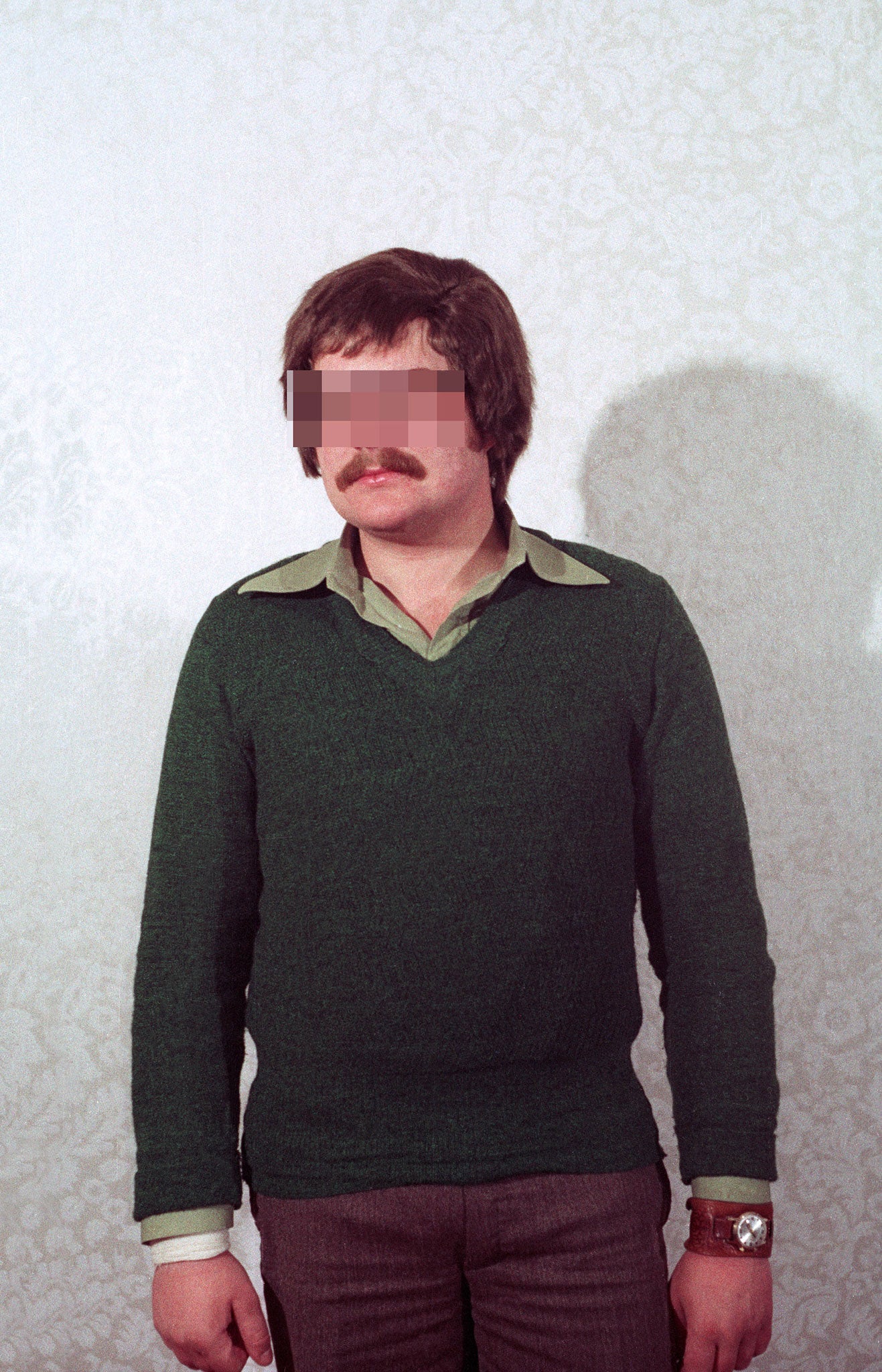

After the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, the vast swathes of material the Stasi gathered about their compatriots was archived, and opened to the public. Now, a new book by the artist Simon Menner brings many of these bizarre but sinister records to light for the first time, from photographic guides on how to apply fake wigs, to coded hand signals and even images of Stasi award ceremonies and parties.

The archive also contains hundreds of thousands of surveillance images. When they became public, many people who'd lived in East Germany went to look at their files, and made the chilling discovery that neighbours, friends or colleagues had informed on them, their everyday activities had been photographed – even that Stasi agents had sneaked into their homes and taken Polaroid pictures.

These were snapped before the Stasi turned houses upside-down, searching for evidence of disloyalty to the state and Western imports. Functioning as quick-developing "before" shots, the Polaroids were used as references for agents to return rooms to their original look. The Stasi might rifle through your underwear drawer, but you'd never know…

It was hearing about such Polaroids that first drew Menner to the Stasi archives in Berlin. "I'm interested in how images work and how they can be used to influence people," says the 35-year-old. "You can read a lot about surveillance, but it's usually very hard to actually see something."

He estimates that there are between two and three million images in the Stasi archive. The process of sorting through the images and getting permission to reprint them (many images had to be pixellated to preserve anonymity) has taken three years.

Even so, says Menner, "I only scratched the surface. It was the extent of surveillance that really shocked me – folder upon folder of pictures of every person who threw a letter into one postbox…"

At first, the people who work in the Stasi archive didn't understand Menner's seemingly haphazard approach: this wasn't about full historical documentation, but about uncovering the most powerful, or off-the-wall, images. But gradually, as he earnt their trust, they came to know his taste, pointing him in the direction of photos that they found particularly striking or eccentric.

"Close to the end, I became curious about Stasi internal affairs – parties and events. You could never ask for something like that – you have to stumble across it. And [the archive staff] would pass on things they'd stumbled on, too."

Many of the images seem funny – being from the 1970s, it looks like state surveillance, Austin Powers style. And there is a value in being able to laugh at forces of evil: it's the ultimate denial of power and fear.

But Menner would never want these images to be viewed as mere quirks: "I hope the laughter sticks in the throat. At a glance these images look funny, then you realise it's serious – it was a terrible, terrible system."

Indeed, for all their seemingly absurd advice on how to dress like a holidaying Western tourist, the Stasi were not to be underestimated. Even at the GDR's last gasp, there were around 90,000 agents. "It was as sophisticated as the KGB or the CIA; it was cutting-edge," insists Menner.

He tried to access similar archives from the UK and West Germany from the same era for comparison – but they wouldn't play ball. "With the Stasi we're in the wonderful position [of being able to access the files] – but it would have been great to show both sides of the Iron Curtain."

Aged 11 when the Wall came down, and having been raised in southern Germany by a family who weren't political, Menner has no personal connection to East Germany. But he has seen the effect the archives can have on those who lived through those times.

Some friends laughed with recognition, saying, "That's just how the Stasi looked." But at one party where his book was passed around, "An elderly man had a breakdown from shock – the Stasi had given him a very hard time. Everything came back to him."

'Top Secret' is published by Hatje Cantz, priced £15.99

All pictures © Simon Menner, BStU 2013

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments