In Brooklyn, the last stronghold of a dying Nepalese language

Seke, a rare, unwritten language from the Himalayas is in danger of disappearing within a generation, yet one building in Flatbush houses some of its last speakers, writes Kimiko de Freytas-Tamura

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The apartment building, in Brooklyn’s Flatbush neighbourhood, is a hive of nationalities. A Pakistani woman enters the lift with a big bag of groceries, flicking a dupatta over her shoulder as a Nepalese nurse and the janitor, a man from Jamaica there to mop up a spill, follow her in.

It is hardly an unusual scene in New York, one of the world’s most diverse cities. But this nondescript, seven-storey brick building is also the improbable home to some of the last speakers of a rare, unwritten language from Nepal that linguists worry could disappear within a generation, if not sooner.

The language, Seke, is spoken in just five villages cloistered by craggy cliffs and caves in a part of Nepal called Mustang, a region close to the border with Tibet. There are just 700 or so Seke speakers left in the world, according to a recent study by the Endangered Language Alliance, a New York-based organisation dedicated to preserving rare languages in the city. Of those, a little over 100 are in New York, and nearly half of them live in the building in Flatbush.

“I live on the fifth floor. My uncle lives on the second. My cousins live on the sixth, and a family friend lives on the first,” says Rasmina Gurung, 21, who came to New York eight years ago from Chuksang, one of the five villages in Nepal where Seke is spoken and that is known for its apples. The remaining Seke speakers live in another building in Flatbush or are scattered across Queens.

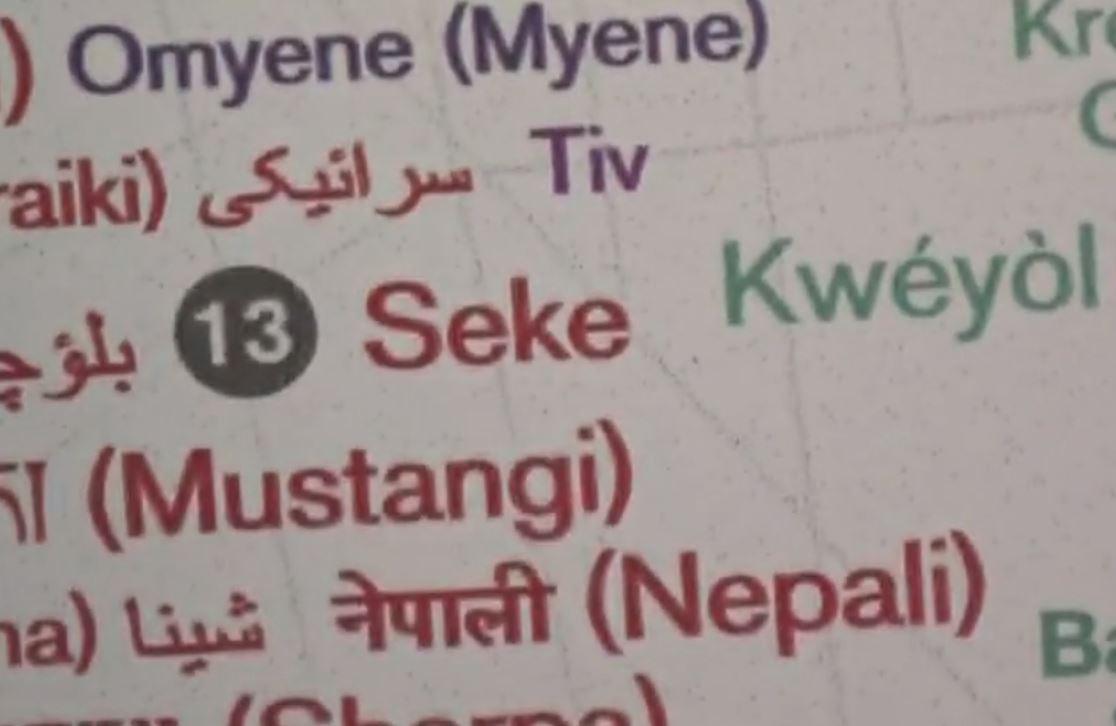

Seke is one of 637 languages and dialects that the Endangered Language Alliance has identified as being spoken across the five boroughs of New York and in New Jersey, which also has a diverse, global population. The Endangered Language Alliance considers a language in peril when there are fewer than 10,000 speakers worldwide. Aside from Seke, other languages in New York that fit that criteria include Vlashki, of Croatian origin, and several Jewish Neo-Aramaic languages, which come from Iran and Iraq.

Another language, Wakhi, from eastern Iran as well as parts of Pakistan, China, Tajikistan and Afghanistan, is believed to be spoken by less than a handful of people in New York, according to the language alliance.

One speaker, Husniya Khujamyorova, 31, who works as a linguist at the organisation, is writing children’s books in Wakhi in the hopes of passing down the language, which is spoken by about 40,000 people worldwide. “People like me, they move at an early age from their country,” she says. “There is not enough material to pass their language to the new generation.”

Even if a language is spoken by only a few people, language experts say it still plays a vital role.

“It’s absolutely invaluable to document, analyse, understand and maintain the linguistic diversity of the planet,” says Ross Perlin, a director of the language alliance and an adjunct professor of linguistics at Columbia University. “But we also see it as a matter of justice – languages are not dying a natural death. They’re disappearing because people have been marginalised and pressured and made to feel bad to speak their language, or they’re swamped by a dominant language.”

Just like diversity with the environment, language loss represents an immense tragedy for the world

“Just like diversity with the environment, language loss represents an immense tragedy for the world,” he adds.

As for Seke, which means “golden language”, legend has it that it was passed down from people living in the snowy peaks of the Himalayas who settled in Mustang, a former kingdom whose terrain was formed, so the story goes, from the heart and innards of a demon defeated in battle by a Buddhist monk.

The apartment building in Flatbush where a number of Seke speakers now live is a microcosm of life back home and a bastion of the language. Many of them were former apple growers who left after harsher winters and erratic precipitation related to climate change made it increasingly difficult to earn a living. In New York, they mostly work as manicurists, construction workers and cooks.

Inside their apartments, it looks as if their former homes had been transported virtually undisturbed from thousands of miles away. Nyaka Gurung, Gurung’s uncle, has built low, wooden rectangular seats along the walls, covered with rugs, a common setup in Nepalese living rooms. Scrolls of Tibetan deities hang on one wall.

On a recent visit, offerings are laid out under a framed photo of the Dalai Lama that hangs above a large plasma television. A thermos used to serve hot butter tea, the national drink of Nepal, stands on a table nearby, and the smoky fragrance of chumin, a Tibetan incense, blends with the smell of Indian spices from the kitchen.

Gurung, who is a nurse, has taken it upon herself to be the de facto preserver of Seke, a language she says many young Nepalese are losing touch with. Children in Nepal are often sent to schools in cities like Kathmandu and Pokhara, where Nepali is predominant.

And Nepalese television is often flooded with Bollywood movies, so many Nepalese absorb Hindi as well. (In addition to English and Seke, Gurung speaks Nepali and Hindi fluently.)

In New York, young Nepalese, like Gurung’s cousins, speak very little Seke. She says she is the most fluent speaker among the diaspora’s younger members and has been helping the Endangered Language Alliance compile a Seke-English dictionary.

It’s hard, because there are so many words you don’t think about in your everyday life – like the word ‘soul’. Who thinks about the soul? I had to ask my uncle. I’m the youngest person holding Seke together. That’s why I feel so much pressure. I need to get as much knowledge as possible. And fast

“It’s hard, because there are so many words you don’t think about in your everyday life – like the word ‘soul’. Who thinks about the soul? I had to ask my uncle,” she says. “I’m the youngest person holding Seke together. That’s why I feel so much pressure. I need to get as much knowledge as possible. And fast.”

Nyaka Gurung expresses both alarm and resignation about how quickly the tongue of his forebears is vanishing. “It’s scary,” he says, as he fingers a Tibetan rosary. “Seke is just going to be a story that you tell your kids: ‘Oh, there was once something called Seke.’”

Rasmina Gurung interjects. “Nepali is the invader,” she says, though adding after some reflection: “But it’s not their fault. We give power to a language because we use it. If we were vigilant, we’d say, ‘No, I’m going to speak Seke.’ But we gave in to the influence.”

Nawang Gurung, a New York-based translator who is archiving languages in the Himalayas, says more than 100 Tibeto-Burman languages were spoken in the Himalayas, but they are not recognised by the Nepalese government and there have been few efforts to teach indigenous languages in schools. “It’s language suicide,” says Nawang Gurung, who is not related to the other Gurungs and does not live in the Flatbush building. The Himalayas are being “colonised by the national language, and this kind of dialect becomes invisible”.

Nepal is currently led by a coalition of moderate communists and former Maoists, and the government has cracked down on opponents, setting off a recent exodus to New York. Nepal became a republic in 2008, ending three decades of civil war and a 240-year-old monarchy. That same year, Mustang, which had its own separate royal family, gave up its king.

Other factors are also causing Seke’s demise, says Nawang Gurung, the translator. In New York, native speakers tend to work long hours with little time to teach their children – and there are no cultural or language centres.

There is also no real demand for Seke. Younger Seke speakers prefer learning far more common languages like Spanish or Mandarin. “They say, ‘What’s the purpose of learning the language when there is no use for it in the future?’” Nawang Gurung says. Instead, a new dialect called Ramaluk is developing among the Nepalese diaspora, he says, which borrows and mixes words from English, Nepali, Hindi and some Seke. “It’s a new language,” he adds.

In a recent YouTube video posted by the Endangered Language Alliance, Jamyang Gurung, who has lived in the United States for 17 years, says he now stumbles when he speaks Seke. “I have all the dialects mixed up,” he says, adding that his son does not speak any Seke. “After 10 years or after my generation, our language will vanish.”

Still, Nawang Gurung, the translator, is somewhat hopeful that Seke speakers in New York could help preserve the language, even if only for a little longer, because they are crowded together. “Back home, it takes two days by horse-ride and long hours of walking to reach a village,” he says. “Over here, it just takes two stops on the subway.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments